During her talk, Eileen Pollack presented a study of professors’ thoughts on qualities of applicants for STEM job positions. The only difference between applications were the names — John and Jennifer. (Courtesy of Eileen Pollack)

Eileen Pollack was one of the first women to earn a bachelor’s degree in physics from Yale.

In 1978, she wrote her honors thesis on advanced mathematical physics, and the paper was eligible for publication in several scientific journals. On her graduation day, she left the manuscript at her adviser’s office and left physics forever.

“I did nothing with the degree,” Pollack said. “I kind of fell apart for a while and eventually made myself over into a fiction writer.”

Pollack, the author of “The Only Woman in the Room: Why Science is Still a Boy’s Club,” visited Lehigh Oct. 13 to speak about sexism in science and engineering fields.

In 1970, women made up 7 percent of all STEM workers in the U.S. By 2011, that number had risen to 26 percent, still 22 percent under the national percentage of total women in the workforce. As previously reported by The Brown and White, women currently represent 28 percent of engineering majors and 15 percent of computer science majors at Lehigh.

Pollack said she had experienced sexism within STEM fields since high school. To see if things had changed since the 1970s, she went back to various educational sites in her life. She found, especially for young women, little had changed.

“The comments that I found still being made to young women are just astonishing,” Pollack said. “One young woman at Yale said her professor said, ‘I’ll grade you on the girl curve.’ A friend in Ann Arbor’s daughter was told by her teacher, ‘Oh, you’re too pretty to be this good at math.’ She lost a whole year from school, not just from that comment, but that comment started it.”

Pollack said societal discouragement affects women who feel more pressured to succeed.

“When places on college campuses have halls of white men, you come in feeling discouraged before even getting there,” she said.

Amanda Krause, a postdoctoral fellow in material science and engineering, said the problem is systemic. She was the only woman in her high school physics and engineering classes.

Krause said most sexism isn’t explicit, but that over time it builds up and affects people negatively.

Pollack said women are brought up to be perfectionists while men are brought up to be more confident.

“(In a study by Shelley Correll, professor of sociology at Stanford), women would study and do really well, but get one or two questions wrong,” Pollack said. “They’d come out of the exam going, ‘I studied so hard I missed this question, I suck at this. Guys wouldn’t study, they’d take the exam, get a B or a C and go, ‘Ha! I passed it.’”

Kate Chamberlain, ‘20, said she relates to this.

“I think I always put emphasis on being perfect the first time and feel disappointed if I don’t,” Chamberlain said. “Here (at Lehigh), if I don’t get the homework right away, my guy friends say it’s fine.”

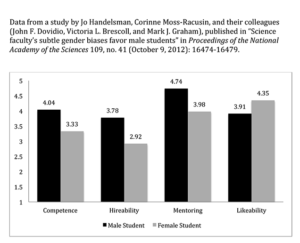

In a study on faculty gender bias, resumes and job applications were sent to professors in different regions of the U.S. in various STEM fields. Professors, both male and female, were asked what they thought about the applicants. The only difference between applications were the names — John and Jennifer.

The results showed professors were more likely to mentor John, rating him greater in “hirability” and competence as well as offering $4,000 more in salary. Jennifer was found to be more likable.

“Imagine you were Jennifer,” Pollack said. “You’d interview for the job and think they loved you, but you wouldn’t get it because they didn’t think you were as competent.”

Pollack said she’s not asking for a lowering of scientific standards, but rather for people to understand diversifying the talent pool would be better for scientific progress. By being aware of the problem of gender bias, Pollack said steps can be taken to promote more diversity within STEM fields.

Attendees of Pollack’s talk offered advice for incoming and current STEM majors.

Lucie Loftus, ‘18G, encouraged students to seek mentors and other women in STEM for guidance.

“There are people out there that want to help and are willing to listen,” Krause said. “Most people want to do right, so talk to them.”

And to women feeling discouraged about their abilities in STEM, Pollack offered wisdom:

“If you’ve gotten as far as you’ve gotten, you’re probably doing better than the guy sitting next to you.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.