Designed by Anna Simoneau

In her four years studying engineering and international relations, Sanjana Chintalapudi, ‘17, has had three female professors. Only one taught an engineering course.

“If I don’t find people, especially women — forget about them being Indian because that’s even fewer — in the fields I’m pursuing, I’d be scared to pursue that field because I would be standing out,” Chintalapudi said. “So I think it’s important, especially at Lehigh, to have diverse faculty, especially in engineering because oftentimes it’s white males. It makes me question how hard of a time I’m going to have pursuing (a career in) my field.”

Diversity in faculty is regarded as a national problem and is reflected at Lehigh. Systemic factors, such as the amount of available minority candidates and their retention by a school, contribute to the problem, as well as the low number of minorities graduating from these programs.

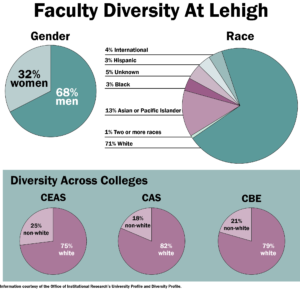

According to the university profile the Office of Institutional Research compiles every year, Lehigh had a total faculty of 521 professors in 2015. Of these, 168 were women. In other words, men outnumber women 2-to-1.

That’s not the only disparity between groups. Out of the 521 faculty members, 369 were white. According to the university’s diversity profile, 3.5 percent of the faculty was black (non-Hispanic), 3.5 percent was Hispanic and 13 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, among other minority groups. These statistics do not break down race and ethnicity by gender.

Percentages for both black and Hispanic faculty members at Lehigh are lower than the national average, which sits at 9.2 percent for black faculty and 4.5 percent for Hispanic faculty, according to a Time article.

The diversity profile breaks down each college’s diverse faculty by placing black (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander and two or more races statistics into what it calls domestic minorities. According to the report, white professors outnumber domestic minorities at a 5-to-1 ratio.

The P.C. Rossin College of Engineering and Applied Sciences has 148 faculty members total. Out of these, 37 identify as domestic minorities.

The statistic did not break down race and ethnicity by gender, but College of Engineering Dean Stephen DeWeerth said women comprise 15 percent of the engineering faculty. He also said they have one African-American professor of practice.

“I think that like every one of our peer institutions, we are not where we would like to be in terms of representation from what are traditionally considered underrepresented groups in engineering,” DeWeerth said. “We as a field, and we as a college have a ways to go to get where we’d like to be.”

In the College of Arts and Sciences, 48 faculty members identify as domestic minorities out of 260. The College of Business and Economics has 16 domestic minority faculty members out of 78.

Each college has a distinct set of problems when recruiting for diversity, but some attribute the lack of candidates to what they call the pipeline issue.

Dean Donald Hall of the College of Arts and Sciences said the pipeline issue consists of candidate pools being less diverse because there are fewer minority candidates graduating from certain disciplines. For example, there are fewer women graduating from STEM fields than men, and this prepares fewer female applicants for faculty jobs.

The challenge isn’t only hiring diverse faculty, but making sure they can rise through the ranks and the university can retain these professors.

“Sometimes it’s not even that the institution is biased in any way or racist, it’s just that if no one is applying for the job, then how do you solve a problem until you get more people to those Ph.D. programs, and then you have more people to choose from,” Hall said.

Saladin Ambar, an associate professor and the chair of the political science department, noticed he was the only African-American in the room at his first department chair breakfast.

“It takes years for someone to become a full professor, it takes years for someone to become a department chair, and if you don’t have those people in the pipeline to begin with, then you know it becomes a very challenging situation,” Ambar said.

Hall said the faculty represents the historical legacy of what institutions’ priorities were many years ago. It takes longer to change the makeup of that population and put new people in place.

However, James Peterson, the director of the Africana studies program, said the pipeline issue isn’t the entirety of the problem. He, along with DeWeerth, said that as institutions of higher learning, universities are the ones shaping the pool of applicants from the people they graduate from doctorate programs.

Faculty can often stay at an institution for 30 or 40 years before they retire. Unlike the student body, which experiences a complete turnaround every four years, the faculty is a longer-lasting population.

“Are we actually creating and contributing to the pipeline that we say is non-existent?” Peterson said. “Because we’re an institution of higher learning, we’re aspiring to be a Research I, we have Ph.D. programs and master’s programs along all these fields. Let’s take a look at our graduate programs: Do we have gender balance along our graduate programs? Do we have first (generation) and diversity balance in our graduate programs?

“That’s the pipeline issue we should be focused on. The more immediate pipeline issue and response to it, it can’t just be, ‘There’s not enough in the pipeline.’ That seems like a cop out now to me.”

DeWeerth said Lehigh needs to look at the climate surrounding these disciplines to make sure it’s inclusive and does not deter people from pursuing doctorates or becoming faculty members.

“We have as much responsibility on the end leading into that, on training Ph.D. students who then become faculty members as we have on the hiring among a fixed pool,” DeWeerth said. “I think we spend oftentimes too much time focusing on trying to recruit from a limited pool than we do in trying to build the pool.”

College of Business and Economics Dean Georgette Phillips also said creating diverse pools may require a little bit more effort, but it is essential. She said when the business school hires new faculty, she requires the pools to have diverse candidates for consideration.

She said the reason for this is if there are no diverse applicants in the pool in the first place, there is no way to end up hiring diverse applicants. Phillips said they’ve been putting effort into creating the pools in such a way that diverse backgrounds are represented while searching for new faculty.

Chintalapudi believes the problem is cyclical. The fewer minority professors students see as they study as undergraduates, the more they become nervous about continuing to pursue these fields. This then deters them from following that route and decreases the number of diverse faculty students see, which only serves to make the problem worse.

“I don’t think we’re going to get that diversity until we address it at this root level where we’re not giving them the tools to succeed at those highest positions,” Chintalapudi said.

She believes having more faculty she could relate to and ask about their experience as women, or as a minority in her field, would have been beneficial to her.

DeWeerth said having minority faculty for students to look up to and to serve as mentors is one part of the benefit. The other benefit of having diverse faculty is that studies have shown diverse groups are often better at solving problems and answering difficult questions. The value of diversity doesn’t just lie in student success, but faculty research success, as well.

Peterson believes hiring diverse faculty is not the hardest part of the issue. He said the work begins with hiring but it doesn’t end there. The retention of diverse faculty is the harder component. To make sure those faculty members stay, Lehigh has to provide an inclusive environment for them to work in.

The number of women in faculty has risen from 20.6 percent in 1998 to 33.1 percent in 2016, according to the university profile. Similarly, the percentage of diverse faculty has also risen.

“My sense is that Lehigh hasn’t tapped out on its diversity for faculty — that we probably still have plenty of room to grow,” Ambar said. “But by no means do I think we have arrived, and I think that challenge mirrors the national challenge to have greater numbers of African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans and so forth in positions on the faculty. It’s a national problem.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

3 Comments

Oh that there would be a way to choose the most qualified person for a position based solely on merit. There has been progress and I am confident that Lehigh will hire qualified and diverse applicants.

Looking at my senior year Epitome; there were 2 black, 1 Asian and 0 female students also 6 female instructors (3 graduate school only). There has been progress.

After time in the military, even in that era an equal opportunity employer, I went to work for a company that a year before had hired it first minority employees for management. The six floor building that I worked in originally had no rest room facilities for females because there were none at the time.

The engineering department had no females until the 1980’s. The original hires were co-ops from a nearby engineering school. Some were hired as full time employees when thy graduated.

The best strategy for hiring and promotion is well known, connections and ability. If you’re lucky you have connections; if not work to make your own. I look at diversity not for itself but for how it relates to ability. What does the diversity add to the goals of the organization. It is obvious to me, having seen changes over time, that Lehigh desired more diversity while maintaining the high quality of its education. The primary goal of Lehigh is to provide a high quality education not a diverse faculty or student body.

Would hope the university would still provide the high quality professors and teachers for our children instead of picking somebody of diversity first to fill that role. With the high cost of tuition, one can only hope that is the goal here. Of course, more power to any great qualified under represented individual so long as we aren’t lowering standards.

I am personally appalled that you as a responsible journalist have not reached out to the office that is responsible for hiring diverse faculty, i.e. the Vice Provost for Academic Diversity.