When Mohsen Mahdawi asked for a favor, his friend hardly expected him to request a 40-foot ladder be constructed for the next day.

He looked at Mahdawi with astonishment and asked if he was kidding.

“I said, ‘You’re an engineer, you can make a ladder, man,’” Mahdawi said. “‘It’s very simple…Make sure it’s strong enough to hold a man.’”

The next morning, Mahdawi found the ladder ready for use. His friend and friend’s brother helped him carry it to the border, preparing for the next step of his plan.

They placed the ladder against the wall. Rope around his arm and pliers in hand, Mahdawi climbed up and saw Israeli land for the first time in his life. Upon peering over, he noticed a military car stationed near his position. It wasn’t safe to cross yet.

A tumultuous upbringing

Mahdawi, ’22, was a third-generation refugee in the al-Far’a camp in the West Bank. He is the oldest of eight, and after his mother left the camp when he was 7 years old, Mahdawi was in charge.

Pictured here is the al-Far’a refugee camp in the West Bank, where Mohsen Mahdawi, ’22, lived until he was 18 years old. The camp is 0.26 square kilometers. (Courtesy of Mohsen Mahdawi)

In the al-Far’a refugee camp, there are gray walls everywhere, according to Mahdawi. The houses are built over each other, an image he calls the “Wasp’s nest.” The camp was started by the United Nations when refugees were displaced after the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. It is only 0.26 square kilometers with a population just over 8,500.

“(It’s) a very crowded, very intense and very irritated space,” Mahdawi said. “Poverty is there.”

Medication in the camp is quite basic. Mahdawi said doctors used to see roughly 100 patients in a typical day.

Water was limited. Schools had 40-50 kids in each classroom, and supplies such as pencils and notebooks were lacking.

“We didn’t have places to play, so after school we would play in the street,” he said.

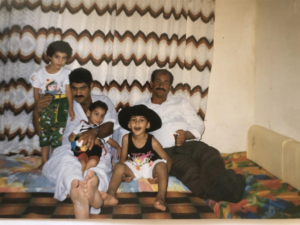

Mohsen Mahdawi, ’22, in the center wearing a hat, poses with his sister from right, Jaffa, his father, his brother Mohammad on his father’s lap, and a family friend. (Courtesy of Mohsen Mahdawi)

When he was 8 years old, Mahdawi’s younger brother, Mohammad, passed away. After this tragedy, he said his life began to get darker.

Two years later, during the second intifada, or uprising, which saw Palestine clash with Israel over the occupation of the West Bank, Mahdawi and his friends were playing in the street after school.

They heard the gunfire of Israeli soldiers inside the camp.

“We were playing basketball in front of the house, in the street,” he said. “The shooting started — da-da-da-da-da — very loud, very scary.”

Mahdawi and his close friend Hemida Mubarak spoke in hushed voices and planned to retaliate. Mubarak was the only other child on the street who lived without a mother, and Mahdawi said they found solidarity in that together.

The two boys discussed their next move.

“We ran into one of the alleys and he said, ‘Let’s throw some stones,’ and I responded, ‘Let’s do that,’” Mahdawi said.

They aimed for the tank, but were too far away to reach it. A different group of soldiers blindsided them in the alley, and as Mubarak turned around to face them, he was shot.

Mahdawi was rushed into a house by a neighbor, still frantic about the events that had just transpired.

After roughly a half hour, Mahdawi went outside to find Mubarak’s resting body on the ground. The soldiers had shot him in the chest.

Upon Mubarak’s burial, Mahdawi felt anger boiling within him.

“We put Hemida in the grave, and the crazy life continued,” he said. “And I get crazy about revenge — stones and Molotov’s weren’t enough for me.”

Mohsen Mahdawi, ’22, who grew up in the West Bank, and his friend Hemida Mubarak threw stones at a military tank in this alley when they were 10 years old. As a result, Israeli soldiers killed Mubarak in this spot. (Courtesy of Mohsen Mahdawi)

He said he often visited the cemetery after Mubarak’s death, sitting next to the graves of his brother and his friend, sharing his thoughts and hoping they could hear him. During one of his visits, Mahdawi’s uncle, Thayer, approached him from behind and sat next to him, looking into his teary eyes. Thayer told Mahdawi to treat the land as if it were his mother, protecting the people in it. He told his nephew that his mind was the only weapon he needs.

“Invest in your mind and live on hope,” Mahdawi recalled his uncle’s words.

A change in perspective

From then on, Mahdawi committed himself to working hard in school in honor of his uncle, propelling him to finish in the top five of his class by the 12th grade. Outside of school, he became a student leader, educating his peers and making them more aware of the world around them. He said he helped them deal with the constant fear of explosions and gunfire.

“I didn’t realize how tough my life was, until I left the camp — until I left Palestine,” Mahdawi said.

At Lehigh, Mahdawi has developed a connection with Rabbi Steve Nathan, the director of Jewish Student Life and the associate chaplain.

“In spite of everything he’s gone through, to still remain an optimist (is amazing),” Nathan said.

Mahdawi was granted a scholarship to study computer engineering at the Birzeit University in the West Bank, and at 18 years old, he left the camp to further his education.

At Birzeit, Mahdawi joined the student council on top of his studies, helping students to become more involved in the community.

“There, life started opening up for me and my perspective started to change,” he said.

David Bisno met Mahdawi when he was working as a bank teller in Hanover, New Hampshire, shortly after he arrived in America.

Mahdawi spends every Thanksgiving at Bisno’s house and speaks to him frequently, to a point where he has almost become part of the family due to his kindness and personability, according to Bisno.

Bisno sees himself as a “sideline mentor” for Mahdawi and is confident he will achieve his goals.

Once, while he was working on the council during a school day at Birzeit, Mahdawi heard a woman speaking in broken Arabic – his native language. Her name was Meagan and she was an American who ventured to Birzeit to study Arabic after earning her master’s degree in the U.S.

Mahdawi said he turned to his friend after seeing Meagan for the first time and told him he was in love.

Fast forward, and Mahdawi and Meagan were living together in Palestine. She would teach him English, and he would help her learn Arabic.

When Meagan was accepted to study medicine in the States, her relationship with Mahdawi became long-distance. They would message each other over social media, and speak over the phone whenever possible.

“This deep, caring connection between us kept happening, and the love (grew),” Mahdawi said.

When Meagan lost a close relative, she called Mahdawi. She was audibly upset, he said, and needed comfort beyond just a screen. He decided he must visit her in America. She told him it was impossible, but he insisted on the journey.

The timing had to be perfect.

Mahdawi had heard bullets whiz by him many times while he was in the al-Far’a camp, and was determined to make it to America alive and well.

A risk worth taking

With the ladder up against the 30-foot wall, once Mahdawi saw the Israeli military car pass by on the other side, he sprung into action. He cut the barbwire with his pliers, tied the rope around the post that poked out of the wall and belayed down.

Mahdawi went straight to the American embassy.

“I convinced them to give me a visa and they said, ‘We will do a background check and send you a passport if you pass,’” he said.

Mahdawi left the embassy and crossed back into the West Bank. This time, he could pass through the gate entrance along the wall rather than climbing back over, since it is much easier to get into Palestine from Israel than the reverse, he said.

Two weeks later, he received his visa in the mail.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Mahdawi said. “I just packed a bag with my clothes and I left to the (Jordanian) border, (which) is controlled by Israel.”

The next challenge Mahdawi faced was at the border in Jericho, an Israeli-occupied land in Palestine.

The Israeli guards checked his passport and discovered his Palestinian identity. After calling him a “troublemaker” for crossing the border into Israel illegally, the guards advised him to sit down and wait for his arrest.

Hours went by, and no one came to detain Mahdawi.

“I said, ‘I’m losing, I’m waiting,’” he said. “‘I’m not going to lose anymore.’”

He approached an officer and explained the situation he was in, expressing his impatience. But, once she checked his name and looked over his passport, she too refused to help because of his illegal entrance into Israel. He sat back down.

This time, he said, he would try a different approach. He walked to her and explained the purpose for his trip to America.

“I said, ‘Please, don’t see me as an enemy. Don’t see my color, my accent, my Palestinian heritage,’” Mahdawi recited his line by heart. “I said, ‘I am a human being, like you. Look at my eyes and you will know that I hurt nobody.’”

He said she started to open up to him after hearing these words. He asserted his desperation to visit his girlfriend in the U.S. after she lost her relative. She understood.

“She said, ‘I believe in you, I believe in love,’” Mahdawi said.

He said the officer gave him instructions to the next checkpoint on his mission: crossing into Jordan discretely. Mahdawi eventually made it to the airport in Jordan — against all odds, he would soon be far away from the conflict he had faced for his entire life.

”I wanted to cry, my heart was in too much pain, but I kept telling myself, ‘Just hold on, stay strong until you get out of (Palestine).’ The moment I left the country, I was crying all the way.”

On American soil

Mahdawi arrived in the U.S. in 2014, and has stayed ever since on account of his acquired green card.

His goals haven’t changed since his conversation with his uncle in the camp.

“I have a dream, a dream of a freedom, a dream which can bring people together where we can share love — where we can save other kids from traumatic situations (like I had),” he said.

Mahdawi strives to become an international leader, and according to one of his close connections in America, this isn’t just a pipe dream.

Don Foster, a supervisor of the English education program at Columbia University, spoke highly of Mahdawi’s charisma, calling him an integral part of his life ever since they met a few years ago in a cafe that Mahdawi managed at the time in Hanover.

“I call (Mahdawi) the ‘Mandela of Palestine’ because what he wants is what (Nelson) Mandela wanted, which is peace among everyone,” Foster said.

Since arriving in the U.S., Mahdawi said he has found truth in all religions he’s had experience with.

“He knows what he wants to see in the world and wants to do everything he can to work toward it,” Nathan said.

Mahdawi is in the IDEAS program at Lehigh, majoring in computer engineering and planning to pursue a degree in international law.

His goal is to connect people, no matter their differences. Mahdawi hopes to build bridges between groups pitted against one another — a dream that can be applied to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At Lehigh specifically, he aims to promote inclusivity on a campus where subcultures are prevalent and can be disconnected from each other, he said.

Over the past two years, Mahdawi said he has given over 60 talks at various locations, including a synagogue in Rochester, New York, and at Middlebury College. His next talk will take place at Lehigh in mid-February, hosted by the Global Union. In his talks, he shares his story and his aspirations to facilitate cross-cultural networks.

“Kids are pure,” Mahdawi said. “Why do we let these kids around the world suffer because of our fears and segregation? We need to break this. All kids deserve the same opportunity, no matter what color, religion, race, background or faith they grow up on.”

Editor’s note: The article was updated with an accurate spelling of Mohsen Mahdawi’s name.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.