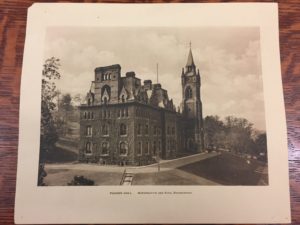

The University Center used to be known as Packer Hall when it opened in 1868. The building was home to the civil engineering, mathematics, philosophy and psychology departments. (Will Newbegin/B&W Staff)

The purchase of Christmas Hall by Asa Packer in 1865 set the first stepping stone in a path toward the mountain slope campus known as Lehigh University.

Lehigh’s storied campus tradition is synonymous with its architecture. That is, to tell the history of the campus’ structural change is to tell its history as a university — dynamic and innovative.

Although The Brown and White, founded in 1894, was not around to document the campus’s earliest establishments, the publication has closely followed university development since its earliest incarnation.

The university’s story begins with what University Architect Brent Stringfellow calls the campus’s “historic core.”

After purchasing Christmas Hall, which was renamed Christmas Saucon in 1872, Packer pursued a greater undertaking. He insisted on a stone-built statement to house his university, which included a railroad line as a means of transporting the building’s material. In 1868, Packer Hall, which is now known as the University Center, opened its doors to all academic and social activity.

In its youth, the triple-partitioned building housed the President’s office, laboratories, classrooms and a museum. For nine decades, Lehigh’s earliest departments of civil engineering, mathematics, philosophy and psychology were also in the University Center.

Lehigh then began to stretch itself outward, and the $100,000 addition of Linderman Library — a roughly $2.4 million undertaking today — marked the first step outside of Packer Hall. Packer named the building after his daughter, Lucy Packer Linderman, and the building was finished in 1877.

“(Linderman Library) is what a lot of people’s mental image of a college library looks like,” said political science professor Al Wurth.

The following years included the construction of similarly-styled Gothic revival pieces, such as Coppee Hall, home to the journalism department and The Brown and White. The building was originally an open-floor gymnasium, which was finished in 1885. Other Gothic-style buildings included Packer Memorial Church, which was finished in 1887, and Chandler Hall — now Chandler-Ullmann Hall — which was finished in 1884.

Chandler-Ullmann, designed by Philadelphia-based architect Addison Hutton and Lehigh chemistry department head William Chandler, optimized the flow of ideas generated inside the building during the time of chemical science’s proverbial gold rush. Due to its state-of-the-art laboratories, the building was recognized at the International Exposition in Paris in 1889.

Lehigh theater professor Pam Pepper, who started working at Lehigh in 1987, had her first office in Chandler-Ullman. She said she felt firsthand the impact of working among such rich history.

“I loved that building,” Pepper said. “The worn stairs. Hundreds of people have walked up and down the stairs. That always resonates with me.”

Stringfellow said he believes that Chandler-Ullman is not only historically important, but also academically important.

“Lehigh’s historic legacy isn’t just how the buildings are old,” Stringfellow said. “From the time that Asa Packer started the school, there’s been an idea that the buildings put on campus should be forward-looking as well.”

Lehigh’s architectural mode of operating thereafter reflected a similar initiative that inspired the construction of Chandler Hall. Lamberton Hall was built in 1907 followed by Fritz Laboratory in 1909 and Packard Laboratory in 1929. These places answered a call for innovative spaces of learning.

Fritz Laboratory’s use of wide-flange steel i-beams, courtesy of Bethlehem Steel, was one of the country’s first, and it hinted at future generations of productive engineering research. On Sept. 27, 1910, The Brown and White printed an update on the new Fritz Laboratory, highlighting the facility’s vertical screw machine, which was the largest in the world at the time.

The Brown and White also followed the progress of Packard Lab throughout its 35th volume. The articles ranged from an alumni discussion about the lab’s plans and approval for the contractor by the Board of Trustees to the first clubs and sessions held in the building.

Pepper said that she experienced the campus’s progression by means of structural change in Zoellner Arts Center, which opened in 1997. She formerly worked in what is now Wilbur Powerhouse. She said she recalled standing inside of Baker Hall with her senior students, tears in their eyes, in response to their new venue of learning.

“It (is) a space for students to be able to tackle new projects—things that they had never done before,” Pepper said. “The physical structure of the building — the office spaces in conjunction with the scene shop and the costume shop — allows us to physically be together, which is so important to what we do.”

Ken Kodama, earth and environmental science professor, said he feels similarly about his own workspace in STEPS, which was finished in 2010. Formerly stationed in Williams Hall, Kodama said the facilities were not optimal for conducting research because he had to carry his own unwieldy equipment up flights of stairs.

“(STEPS) is a really up-to-date, modern facility,” Kodama said. “(Students can) learn how to do measurements and how to analyze data.”

The Brown and White printed an article in Vol. 115 about the new addition to the campus. Tony Hanna, director of community and economic development of Bethlehem at the time, said STEPS would set an example and improve the university’s relationship with the city.

As Lehigh embarks on future developments, such as its Path to Prominence campaign, Stringfellow believes that the university will keep similar interests in mind.

“We want to… create better pathways, better connections and better relationships,” Stringfellow said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

6 Comments

Therefore to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Packer Hall’s – that is, the U.C.’s – founding, its legacy, as well as the university and our campus more generally, we are going to tear down the back third of the structure (erected in 1958) and then coat much of the northern front with a glass wall? Is this a celebration, or is it an effacement…? I would submit the proposed renovation, by the administrators, should be considered a suppression of the past, even a dissolution of it.

One can have modern architecture on campus, and even close to the older buildings, if planned carefully and respectfully. Deconstructing much of the exterior walls of our U.C. – a beautiful building, really, by American standards – is hardly a celebration of it, and more so a wish that it would somehow go away.

Do we really want this…? I am very disappointed with the relative lack of complaints and activity on campus, by students and professors, even administrators, about the proposed ‘renovation’ to our founding structure. The project is proud and thorough in its dissolving the past, and so is really rather shocking given the conservative nature of Lehigh historically.

Dr. Simon has come from Virginia, along with the appearance of other administrators, and so has discovered a peach of a building in which he can funnel a lot of money and resources at, creating a vast re-interpretation, while quashing the past. A building that had fortunately sailed all through the 20th century, to be finally dissolved in the 21st? What building will be next…?

A more logical approach is to leave the core of our campus as it exists, more or less, while emplacing newer structures around it, on the periphery, or in respectful conjunction to it. Mr. Stringfellow, and others, will speak of our ‘historic core’, yet how little they truly seem to appreciate and understand it….

Would someone be able to explain the reasoning behind the brick arch located on Packer Hall (UC)? It seems to be incompatible with the rest of the stone building.

Replying to Mr. Davenport: You mean the brick arch, high up on the eastern end of Packer Hall? (This being the end opposite the tower end, and visible in the photograph.) Yes, I have wondered a bit about this myself… That massive brick arch actually joins together two tall chimneys. There were many chimneys funneling out of the old Packer Hall, servicing numerous fireplaces, perhaps even on the order of 20. The chimneys had to be quite tall in order to clear the Mansard roofing. So at the extreme eastern end the chimneys would have appeared awkward if left alone, being somewhat ungainly as two tall, lank chimneys so close to each other. Therefore, a bridge, or an arch, was emplaced between them, making them seem much less unwieldy. The bridge was however additionally functional in the stabilization of both structures.

Additionally, Robert, and as an addendum to my last post, I have learned there was actually a complementary second brick arch on the building, of the same design and no doubt constructed for the same reasons. It was located roughly mid-building, but at the other end *of* the larger, rectangular, eastern portion of Packer Hall. [If you divide the original structure, “Packer Hall”, into three parts, there is, firstly, the larger eastern end, with seven windows on the north and south faces on the 1st and 2nd floors; secondly, the slim middle section, which now houses the dining areas and the Asa Packer Dining Room on the third floor; and finally, the third, tower, west end.] This other brick archway was therefore located mid-building, when the structure is considered as a whole. It would not be visible in this present photograph.

Thanks. Your explanation makes perfect sense. Often a utilitarian solution to a problem fails to provide an artistic success. A brick arch that would be pleasing if located at any of several locations on campus but is ugly where it is located. Probably the cost of removal is the reason it still exists. Being obvious only from the east and being four stories in the air it is fairly well hidden in plain sight, that may lessen the incidence of dysphoria.

The proposed glass wall will be more obvious. Will it be perceived as ugly? The use of glass at the power house, I think this is true, would seem to be a structure enhanced by glass. Packer Hall/UC may not be the right location for the use of massive amounts of glass.

I forgot to mention: I believe Packer Memorial Church should rather be classified as Romanesque than Gothic. Linderman Library – also – was originally a Romanesque structure until it was reinterpreted in a vast renovation/expansion circa 1929. A very successful project back then, and so in a sense I suppose you might say this was one of Mr. Stringfellow’s renovations of a “forward looking” type.

———————————————————-

In a reply to Mr. Davenport, I don’t think the massive arch high on the east end of the U.C. is ugly or even unaesthetic. I rather view it as one of the quarks of the building, neither really pretty nor unattractive.