The cost of college has skyrocketed over the past four decades, and only continues to climb higher.

Meanwhile, the cost of textbooks lies beneath the radar, crammed inside the broader issue of college affordability.

A July 2018 survey conducted by Morning Consult on behalf of Cengage, a digital education company, found that 85 percent of current and former students believed “textbook and course material expenses” were financially stressful, more so than other categories like food, housing, and health care, and second only to tuition costs.

Jennifer Swann, a professor in biological sciences and Lehigh’s former director of student success in the College of Arts and Science, said she knows students are struggling to afford their course materials.

She said oftentimes, she would only learn a student was unable to afford the required textbooks after the student was sent to Swann for a disciplinary warning.

Swann said her concern is that more faculty need to be aware and proactive about the issue to effect real change, and cautioned that as Lehigh attempts to admit more diverse and socioeconomically disadvantaged students, problems with textbook affordability will become more prevalent.

Swann said she has pushed for faculty to use open access resources, like the free OpenStax program run through Rice University.

But she says in general, faculty aren’t thinking of new ways to teach or deliver content.

“I think the problem is bigger than we think it is,” Swann said.

Because Lehigh’s Office of Institutional Research said it has not conducted its own study on textbook affordability, The Brown and White surveyed faculty and students — separately — to gauge the issue on campus.

The results were striking

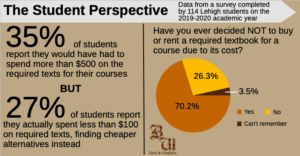

Out of 114 student respondents, spanning across Lehigh’s five colleges and all class years, 7 in 10 students reported having not bought or rented a required textbook for a course due to the textbook’s cost within the past academic year.

The student survey also showed a significant disparity between what students were asked to spend on textbooks deemed necessary for their courses in the past academic year and what students actually reported spending on required textbooks.

For questions pertaining to cost, students were asked to assess price options as if they were going to rent the book from the campus bookstore for consistency. Response options were listed by $100, ranging from “less than $100” all the way up to “more than $500.” About 1 in 3 students reported their required textbook costs were more than $500 for the past academic year — the most commonly reported answer compared to any other price range.

However, more students — nearly 30 percent — reported they actually spent less than $100 on textbook costs, in the past academic year, compared to any other price range.

For the purposes of the survey, “textbook” refers to any required text a student needs to acquire for a course. Both the faculty and student surveys were anonymous, but both surveys gave respondents the option to leave a name or share their thoughts in written form.

“It’s unfortunate that many classes make the use of textbooks mandatory without considering the cost for students who may not be able to afford them,” said one sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences. “In the end, the student who truly cannot pay the hundreds of dollars associated with the cost of textbooks is at a disadvantage.”

More than 75 percent of students reported they are most likely to acquire textbooks through Amazon, with the campus bookstore and Chegg coming second and third, respectively. About two-thirds of students said they preferred physical textbooks to a digital book.

Several students shared their frustrations with a perceived contrast between what faculty say is necessary for the course and what is truly a necessary component to learn the material.

“I feel as though as much as the cost is an issue, another issue is most professors require these textbooks online through the bookstore and don’t actually need them,” said Anna Bunnick, ‘21, a civil engineering major. “I try to be as cost efficient as possible and rent from the cheapest site, either Amazon or Chegg. At least three of my six classes this semester I rented books for I have not opened or used for assignments this semester. By the time I realized that we weren’t going to need the book, it was too late to return them online.”

Some faculty try to get creative

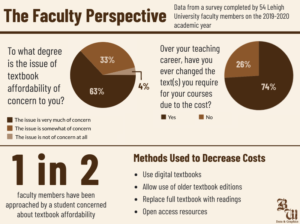

A separate survey was administered to faculty on the issue of textbook affordability. Out of 54 respondents, half said they have been approached by a student expressing their concern over their ability to afford texts required for the class.

Forty-four out of 54 respondents said they considered themselves to be “very aware” of the price of the textbooks they select for their courses. Sixty-three percent said textbook affordability is “very much of concern” to the respondent, compared to “somewhat” of concern or “not of concern at all.”

But only 15 percent of respondents said the issue is “very much of concern” to the Lehigh faculty at large.

While three-fourths of respondents said they have changed their required texts due to the cost over their teaching career, Virginia McSwain, an associate professor in physics, said this can come with sacrifices.

McSwain teaches the Intro to Astronomy course that can seat between 30 and 150 students. She still requires a textbook — “we absolutely, 100 percent still need them” — but in part after she would photocopy entire chapters for students in her higher level classes who were unable to afford the book, she made the switch to a free digital OpenStax astronomy textbook.

McSwain said it wasn’t an easy decision to change course. She said since there are always rapidly changing data, missions and pictures in the field of astronomy, new editions of books are important and “consolidate the main points… to convey it efficiently to students” who may not have developed the skills yet to seek out “high quality information” on their own.

While the OpenStax resource she turned to updates its editions in a timely way, she admitted it also required her to lower her standards.

“The free book is not as good of quality as the books that my students could be spending money on. I am not as happy with the quality of the book,” McSwain said. “The content of the book, the organization is not ideal at all. But I’m willing to sacrifice that.”

Dork Sahagian, a professor of earth and environmental science, developed a different approach to the textbook affordability issue.

Sahagian came to Lehigh in 2004. He remembers an email from then-Provost Mohamed El-Aasser in the mid-2000s — reminding faculty to be conscious of the cost of their required textbooks — prompting him to make a change in his intro to environmental science course.

He said with books between $100 and $300 each, he knew he had to do something.

So, Sahagian wrote his own textbook.

“A User’s Guide for Planet Earth,” published through Cognella, came out in 2012. Sahagian wrote the book with the specific intention of saving his students money.

He told Cognella that he wanted the book to cost no more than $60 — and he’s proud to report that to this day, even after publishing an updated edition in 2019, that the book still costs his students no more than $60. Sahagian, whose intro course is taken by as many as 150 students per year, said he places several copies of the textbook on the course reserves at the library in case students are still unable to afford the reduced price.

He said he makes little money off the book.

“I wrote the book to be both affordable and useful for the students,” Sahagian said.

He said he is moving away from requiring textbooks for his advanced and graduate classes, but he does feel a need for his introductory course to require a textbook for basic concepts and as a supplement to class lectures.

The balance between individuality among faculty and a one-size-fit-all approach from the administration, though, is a fine line, Sahagian said.

“Professors are notoriously independent when it comes to this kind of thing,” Sahagian said. “But, it was an email from the provost that alerted me and brought to mind that as an institution, the university cares about this. Maybe all that is needed for faculty to hear from time to time is — ‘Hey, check it out, these students are spending too much money, and it shouldn’t be as much on textbooks.’ To be heavy handed is difficult — faculty would not respond well to edicts from above on how to teach their classes.”

Lehigh tuition shoots up

Lehigh has followed the trend of increasing costs for college — an issue which has made splashes in headlines around the country and has meandered its way onto the presidential debate stage and into the nation’s popular culture. Lehigh raised tuition by 4 percent for the 2020-2021 academic year — almost double the 2.3 percent average annual growth rate for the cost of college. The increase follows multiple years of Lehigh tuition increases by 4 percent or more.

It now costs more than $72,000 per year to attend Lehigh, including room and board for a first-year student.

All of this while wages grew on average only 0.3 percent annually between 1989 and 2016, according to Forbes.

Some of the textbook options for students

Monika Skuriat Fritz, Lehigh’s director of Retail Partnerships and Marketing, said in an email that faculty members are able to stock required textbooks each semester at the campus bookstore. She said the bookstore’s operations are contracted out to Barnes and Noble.

Though Fritz said the split in profits between Lehigh and Barnes and Noble is “protected contractually,” she added that the bookstore will apply “an industry standard margin” to the cost of a textbook set by its publisher. This “standard margin” covers expenses like freight and labor, “to receive, shelve and return excess inventory” along with the costs “to maintain both a physical and online bookstore.”

A percentage of the bookstore revenue, Fritz added, goes to support Lehigh financial aid and scholarship initiatives.

Swann lamented that the bookstore is a “victim of the situation,” often ordering more books than the students can afford, resulting in “huge waste of time and money” when the unsold books must be shipped back to a warehouse. Fritz, however, said the bookstore generally “has a good idea of the number of materials that will be needed for a certain course, and can order accordingly.”

Fritz highlighted the bookstore’s Price Match program, which she said is popular among students and “ensures students get the best prices available on their course materials,” along with rental and digital options.

“The Lehigh University bookstore is a full-service store whose sole mission is to ensure that the right textbook, for the right class, is on the shelf at the right time,” Fritz said. “This commitment to service includes stocking every book that is requested for every class, even obscure foreign language books, customized course packs and loose-leaf format textbooks. Online textbook competitors do not provide that type of guarantee. … In addition, they do not have the same commitment to stocking textbooks for every student who wants one.”

John McKay, the senior vice president of communications for the Association of the American Publishers, cited a Student Watch study that found a 35 percent decline in student spending on course materials over the past five years.

Meanwhile, McKay said the average full-time undergraduate student this year is buying or renting roughly two less textbooks compared to the 2015-16 academic year.

“Publishers are working hard to provide students with affordable options, including subscription models and digital models that can be purchased in bulk, which leads to greater affordability,” McKay said in an email.

Pearson, the British-based publishing company, deferred comment to McKay.

McKay said the subscription service model allows students to access “massive digital portfolios for one set price,” while the Inclusive Access model allows publishers to negotiate with individual schools for discounts based on large volume sales — thus passing the savings on to students.

He added that renting textbooks is a continuously growing market.

Cheryl Costantini, the vice president of content at Cengage, agreed that affordability is the focus for those involved in higher education.

Costantini said “Cengage Unlimited” is one way the company offers savings to students. The program allows subscribers to access over 22,000 digital course materials for $120 per semester. Costantini said with over 2 million subscriptions sold since the program started in 2018, students have saved over $125 million. And Cengage Unlimited eTextbooks, set to launch in August, gives students access to over 14,000 eTextbooks for $70 per semester. The program will also allow students to order four print rentals for $8 each, plus shipping.

“As for updating books and producing new editions, our focus is on updating books when they need to be updated for currency, new discoveries, or new ways of thinking and learning,” Costantini said in an email. “We are also focused on how to bring our content to life through the use of technology. … Overall, our energy is spent on delivering the highest quality and best learning content in the market in a format that students want.”

With a growing field of options for course materials, and as students and faculty navigate cost concerns, McSwain and Sahagian agreed that more can be done to address the issue. However, the nuance to the issue may slow progress on a potential solution.

“Faculty in different departments and fields have radically different options,” said Joshua Pepper, an associate professor in physics. “Some faculty have the option to choose high-quality open textbooks that are free electronically and cheap for physical copies, while in some specialized fields, the only textbook option is a single high-priced text. So while the problem is widespread, any solution will have to be field-specific.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.