Sexual assault is a traumatizing experience, leaving people hurt, vulnerable and furious. Nationally, and here at Lehigh, Title IX offices are tasked with protecting students who experience sexual harassment, violence and discrimination. However, some students report that the drawn-out Title IX investigative process adds to their anguish.

Lehigh University’s Title IX Office promises to respond to allegations of sexual harassment and misconduct and to generally resolve cases within a 60-day timeline, though this suggestion is not federally mandated. This timeline has not been the lived experience of some students who have seen cases lasting months past the 60 days, even reaching a full year.

Three women have shared with The Brown and White their experiences, documents and email exchanges detailing Title IX formal investigation processes that took between five and 12 months. The Title IX Office did not consistently provide regular updates in any of the three cases and in two of the cases, attorneys for the victims got involved in light of timeline issues.

The allegations of the three cases range from sexual misconduct to sexual assault. The nature of the reports and investigation timelines were verified through a review of email transcripts and final reports the alleged victims shared with The Brown and White investigative team.

Title IX language and technicalities

The University’s Policy on Harassment and Non-Discrimination states the Title IX Office “takes steps to respond promptly and effectively to allegations of sexual harassment and sexual misconduct.” The office assists students and faculty with cases, counseling and investigations.

Sections 6.2.5 and 6.3 of the Revised Title IX Policy on Harassment and Non-Discrimination state that cases and their subsequent investigations — whether formal or informal — will “generally be resolved within sixty (60) calendar days of the filing of the complaint.”

However, if a case were to take over 60 days due to “extenuating or unforeseen circumstances,” the policy states that “where there is a need to extend this timeframe, the parties will be notified of any delays and provided an explanation for the delay.” Parties will also receive regular updates regarding the status of the complaint, the policy states.

In explaining the 60-day timeline, Lehigh’s Title IX Office coordinator Karen Salvemini said this guidance was rescinded, and in 2020, new Title IX regulations were issued which did not state a specific timeframe within which a complaint must be resolved. However, the most recent policy available on Lehigh’s website, dated Aug. 14, 2020, and titled “Revised Title IX Policy on Harassment and Non-DIscrimination,” still says that complaints will generally be resolved within sixty (60) calendar days of the filing of the complaint. Director of the Office of Student Conduct Holly Taylor said that Lehigh adopted this language because it had previously been recommended by the Department of Education.

Attorney and professor of law Peter F. Lake said while there is no hard federal timeframe mandate for Title IX cases, in 2011 the Department of Education guided institutions to work within an investigation frame of 60 days.

Lake teaches at Stetson University’s College of Law in Florida and is a senior higher education attorney at Steptoe & Johnson PLLC. According to Steptoe & Johnson’s website, Lake is “a nationally recognized expert on a variety of higher education topics, including Title IX.”

“It was never a rule, but rather just guidance,” Lake said. “A lot of people incorporated the 60-day guidance into their policies, and it’s been there ever since.”

Lehigh is one of the schools that adopted the federal guidance into its policy.

“It is very common for complex investigations to take significantly longer than 60 days,” Lake said. “Also, specific prior notice at the outset of an investigation that may take more than 60 days has never been federally mandated. If it is going to go longer than 60 days, you’re not required to say that the case will go beyond the timeframe, unless institutional policy so provides. Some institutions have such policies internally.”

Lake explained that each investigation is different, and the 60-day timeline is more of an aspiration rather than a promise – and is often an unrealistically short time frame.

He added that there are some cases that open and close in a matter of days, but the complex ones tend to go well beyond 60 days. He said if you are dealing with multiple witnesses, evidence and a police report, the process might take months to reach a resolution.

Furthermore, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), makes it hard to disclose information throughout the investigative processes.

“In a public justice system, you would be able to track this in a very public way,” Lake said. “With FERPA, it’s such a block to be able to observe what’s going on, which I think leads to a lot of suspicion and, frankly, criticism, because you don’t always know what’s going on.”

Lake said FERPA and the 60-day timeframe may pit students and universities against one another.

Institutions’ inability to complete cases within the 60-day window has left some students feeling downtrodden and defeated, thereby impacting their psyche and academic performance. Some universities’ Title IX offices are understaffed, forcing one person to do the job of many. Fresno State, Connecticut College and Harvard University are a few examples to be reported on in the media. This obstacle makes it difficult for both students and Title IX staff to come to a compromise and finish cases in a timely manner.

Alleged victims’ stories

Three students have shared their stories with The Brown and White. Due to the sensitive nature of their cases, the students asked to be identified by their initials and class year, only.

C.L.

(Jenna Simon/B&W Staff)

C.L., ‘23, said she was sexually assaulted in December 2018. An email chain she shared with The Brown and White shows she first reached out to Salvemini to inform her that she wanted to pursue a “university process” on May 10, 2019. A university process is a proceeding handled internally and not in conjunction with the criminal justice system.

The university officially opened C.L.’s case on June 20, 2019, and the alleged assaulter was ultimately found not guilty of sexual assault on June 4, 2020, after a period of 12 months.

Over the summer of 2019, C.L. emailed Salvemini twice expressing concern about the lack of updates regarding the status of her case.

On June 19, 2019, in response to C.L.’s first email, Salvemini said it would be best to start the investigation in July when the investigators and Taylor would be back in the office. C.L. agreed to wait.

C.L. emailed Salvemini a second time on July 23, 2019 and said, “I must admit that I feel like I’ve been left hanging for long periods of time during this process. Between my anxiety over the constant waiting and the overall high stress of reliving what happened to me, I’d appreciate if in the future you could keep me more consistently updated on the case. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about this, so even if there’s nothing going on, an email here or there to keep in touch would make everything a little less difficult for me.”

Salvemini responded on July 25, 2019, apologizing for the lack of updates.

Between July 25 and Sept. 6, C.L. and Salvemini emailed back and forth, sharing evidence and setting up meeting times.

From Sept. 6, 2019, to Jan. 28, 2020, C.L. received no correspondence from Salvemini. Two faculty advocates emailed Salvemini on behalf of C.L., as well, but neither received a response.

C.L. eventually met with Salvemini after nearly five months of silence. During this meeting, the Title IX coordinator said she would aim to wrap up the case within the next month. The case ended up concluding six months later.

During the waiting period, C.L. reached out to a staff member who works as an advocate through the Gender Violence Office in hopes of speeding the process up. Advocates are Lehigh staff and students who support survivors of gender violence. C.L.’s advocate later emailed a member of the administration to question the length of her case.

“I have been working with a student, (C.L.), for about a year now and she has not had any resolution with her case,” the email read. “She has met several times with Karen (Salvemini) and has been told that she would be communicated with repeatedly and has failed to receive said communication on several occasions. … I am in touch with C.L. regularly and she asked that I reach out to folks on her behalf to ensure that what is happening to her does not happen to others.”

On April 15, 2020, C.L. emailed Salvemini and Taylor, asking to be updated on the state of her case.

“The last time I heard from you or your office was in February,” the email read. “To be clear, you expressed to me when we met on January 28th that you wanted to wrap up my Title IX case by the end of February. It is now April 15th. You also assured me that I would receive weekly updates, which also stopped very shortly after they started.”

C.L. further went on to write that she was exhausted “of being held in limbo” by the Title IX Office.

In response, Taylor wrote, “in an effort not to muddy either process, Karen (Salvemini) and I paused this investigation briefly. Since the physical closure of Lehigh’s campus, both Karen and I have had to reprioritize our case loads but are now ready to move forward with your case.”

As the case was concluding, Salvemini sent C.L. an email on May 20, 2020, with the recommended verdict she would later send to a panel tasked with affirming or denying the decision.

“We find that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that Respondent engaged in sexual misconduct (dating violence) and sexual harassment against Complainant based on the information summarized herein,” Salvemini’s email said.

However, one day after sending the email, Salvemini told C.L. there was a typo in the document. She then sent another email on May 21, 2020, containing a corrected draft of the final report.

In the new draft, the word “sufficient” was changed to “insufficient.” Otherwise, the entirety of the 30-page document read exactly the same.

“We find that there is insufficient evidence to conclude…” the updated version read.

C.L. emailed Salvemini, upset with the handling of the typo.

“I find it incredibly discouraging and irresponsible, and honestly a little unbelievable, that the only ‘typo’ within a 30 page document occurred in the verdict of your findings,” she said. “I was feeling very hopeful after reading over your conclusions yesterday, and now that has been taken away from me suddenly.”

In the end, C.L.’s alleged abuser was found not guilty of rape.

J.D.

(Jenna Simon/B&W Staff)

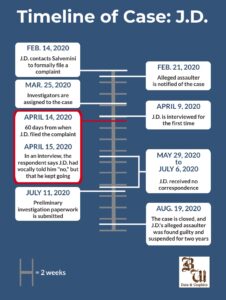

J.D., ‘23, said she was raped in the spring semester of her freshman year. Her case lasted from Feb. 18, 2020, to Aug. 19, 2020 — four months longer than the 60-day window.

In an email chain shared with The Brown and White, Salvemini reached out to J.D. on Feb. 10, 2020, following up on a message from a mandated reporter. J.D. met with Salvemini for the first time on Feb. 12, and Salvemini put her in contact with the assistant dean of students. J.D. emailed Salvemini on Feb. 14, asking if she could formalize the complaint.

The alleged assaulter was notified of the case on Feb. 21. Investigators weren’t assigned to the case until March 25, over a month after the case was formalized through the Title IX Office.

J.D. said she was interviewed for the first time on April 9. The respondent was interviewed on April 15, according to J.D.’s final report, which she shared with The Brown and White. He admitted J.D. had vocally told him “no,” but that he kept going.

The preliminary investigation paperwork was submitted on July 11, five months after the case started.

Both J.D. and her lawyer contend that the investigators were biased and stretched the case out much longer than necessary.

Her lawyer emailed the Title IX Office three times to ask why the process was taking so long. J.D. received no correspondence between May 29, 2020, and July 6, 2020.

J.D.’s lawyer eventually reached out to the office again on July 6 after nearly a month of no communication. Her lawyer asked about the status of the investigation and for a timeline of the remainder of the process.

Salvemini responded with an update and assured them that the report and subsequent panel review would most likely be finalized in one to two weeks.

In an email sent on July 20, J.D.’s lawyer again questioned the office’s slow pace.

“You (Salvemini) had stated in your email two weeks ago that the plan was to have the report complete that week, so I am hoping it will be ready to be reviewed by the parties this week.”

After some back and forth between J.D., her lawyer and Salvemini, the case was closed Aug. 19, 2020.

J.D.’s alleged assaulter was found guilty and was suspended for two years.

J.D. has since transferred to another university, citing the handling of this case as one of the main reasons for her leaving.

“Since my own case, I have heard numerous stories of other women who have tried to go through the Title IX Office or who have been too scared to go through the process,” J.D. said. “I just don’t feel confident that Lehigh would protect me or any of my friends if something were to happen.”

J.D. said if something were to happen to her again, she would rather deal with it on her own than go to Lehigh with it.

“That is not how a student should feel in college,” she said.

E.F.

(Jenna Simon/B&W Staff)

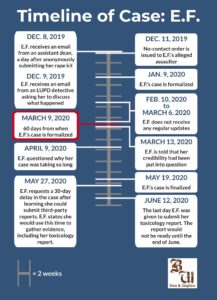

E.F., ‘23, said she was raped by a student living on her floor during the first semester of her freshman year. She said she felt pressured to speak with the Title IX Office after Salvemini learned of her case through the Lehigh University Police Department. E.F. also hired a lawyer.

At the hospital, E.F. was told survivors could submit their rape kits to LUPD and they would be kept anonymously for up to two years. On Dec. 8, 2019, the day after E.F. anonymously submitted her rape kit to the police department, she received an email from an assistant dean who had learned of her case from LUPD. E.F. explained that the assistant dean said she was notified of E.F.’s “traumatic event” and offered her the option of postponing finals and finding alternate housing. E.F. had not reached out to the school prior to this email and did not know how the university knew about the incident.

On Dec. 9, 2019, an LUPD detective emailed E.F., asking her to call the police department to discuss what had happened to her. E.F. said she felt forced into speaking with LUPD since she had wished to keep her rape kit anonymous and not discuss the incident further.

A no-contact order was issued to E.F.’s alleged assaulter on Dec. 11, 2019, and the case was formalized on Jan. 9, 2020. It lasted a little over five months.

E.F. had several witnesses to her case and a positive sexual assault kit performed at St. Luke’s Hospital, which ultimately was not considered to be enough evidence in the eyes of the Title IX Office. As noted in the final report, the alleged assaulter admitted to having sex with the victim during his interview, so it was difficult for E.F. to prove it was nonconsensual despite the evidence she submitted.

E.F. did not receive any correspondence from the office from Feb. 10, 2020, to March 6, 2020, and did not receive any regular updates during this span of four weeks.

On March 13, 2020, E.F. spoke with the investigators on Zoom and was told that her credibility had been put into question.

In an email on April 9, 2020, addressed to the investigators, E.F. questioned why the case was taking so long to conclude.

“I was told this would take up to 60 days, even after Christmas break, and I do not understand how it’s even legal for this to be taking so long,” E.F. said in an email to the investigators.

The case was finalized on May 19, 2020. Soon thereafter, E.F. learned of her ability to submit third-party reports, which would provide additional evidence, and she requested a 30-day delay in the case. On May 27, 2020, E.F. asked if she could have a month to gather the evidence she requested.

Salvemini responded, writing, “On May 27, 2020, you indicated that you did not know that you could submit third-party reports and that your own toxicology report would be forthcoming. As I mentioned previously, I do not know why you believed you could not submit third-party reports prior to reviewing the investigation draft. Taking all of this into account, as well as the fact that I do have a responsibility to both you and the Respondent to continue to move the case forward, you may provide the toxicology report that you’d like to submit on or before 5:00pm on Friday, June 12, 2020.”

This gave E.F. two weeks out of the month she requested to hand in the toxicology report, which would not be ready until later in June.

In response, E.F. said, “It is entirely unclear to me why you would assume that I have knowledge of what is and is not permitted to be introduced in a Title IX investigation. I have never been raped on a university’s campus before and, therefore, I have never been through this process before. … With that said, this investigation has taken six months to this point. I cannot fathom that a few more weeks is going to be the time period that throws this investigation from ‘concluding’ and into the category of ‘languishing.’”

E.F. never ended up sending her toxicology report because she felt as though the office was doing everything in its power to undermine her and she did not want to continue retraumatizing herself.

The police chief’s perspective

Near the end of August 2021, E.F. approached LUPD Chief Jason Schiffer, hoping to talk to him about her case and offer insight as to how to conduct investigations moving forward.

After this conversation, Schiffer was able to reflect on the outcome of cases, especially E.F.’s.

“A lot of us are disappointed in the outcome of that investigation,” Schiffer said. “Unfortunately, most of these cases do not go in the direction of the survivor’s liking.”

LUPD conducts sexual assault and harassment cases independent of the Title IX Office. Police investigations go through the District Attorney’s Office.

“It is incredibly difficult to successfully prosecute cases of sexual assault, and the District Attorney’s Office is tasked with making decisions about whether to have charges brought, based upon the facts available in any of these investigations,” Schiffer said. “I understand why the decision was made not to prosecute, but often decisions like this are hard to accept.”

In regards to Title IX cases, Schiffer said he is aware of cases that have gone over 60 days.

He said it is his understanding that the 60 days is a guideline, and depending on the complexity or issues of the investigation, it can extend beyond that timeframe.

“I think that the (Title IX) office is overwhelmed and needs more resources, like more staff members,” Schiffer said. “The size of the population of the school and the nature of those investigations require more resources. They have one person doing the job of many. The most well-meaning people can’t do more than they can do.”

Advocates and their role

Brooke DeSipio is the director of Gender Violence Education & Support and head of the advocate program. Her responsibilities include recruiting advocates, coordinating on-call scheduling and training new members.

“One of the things that is really unique about the advocates is they have a designated role at Lehigh to just offer support,” DeSipio said.

Throughout her work with the program, DeSipio has noticed cases going beyond the 60-day mark.

“The timeline varies depending on the specifics of the case,” DeSipio explained. “If someone comes forward and reports in May, the case may spill over into the next academic year because the school can’t get students in for interviews. The most important thing is that we have a fair investigation and do the student right.”

DeSipio said cases reported around finals or before summer break typically get pushed back to the next semester. She explained certain circumstances will lengthen the timeline of a case, such as the number of witnesses and subsequent interviews. She said if the victim wants the investigators to talk to more people, the case will take longer, as well.

If a student feels as though they are experiencing significant delays in the Title IX process, DeSipio encourages them to reach out to advocates to see if they can help.

Scott Burden, director of the pride center, is part of the advocate program and works under DeSipio.

“As an advocate, my job is to believe and support victims of gender-based violence,” he said. “We can also be connected to support services or to students who may need support through other channels.”

Burden has heard of long cases occurring during his time as an advocate, including cases that lasted well beyond two months.

“A lot of our victims and survivors, when they hear the options, say they don’t want to go through the Title IX process, and I believe that is because they are afraid it will be a long, drawn-out process,” he said.

Burden said he has heard students openly share about their issues with the Title IX Office as well as the reporting process.

Burden encourages students to reach out to the advocate program if they feel the case is too stressful for them to handle on their own.

Administration response and commentary

As part of her job as Title IX coordinator, Salvemini said she is responsible for overseeing the response to incidents of sex discrimination. This includes arranging supportive measures, connecting individuals with support resources, and initiating and implementing university processes to investigate and address the reported behavior.

Both Salvemini and Taylor said many factors influence the longevity of a case. This includes availability of students or witnesses, impacts or delays from external processes such as criminal investigations, numbers of interviews, accessibility of evidence, outside legal counsel and the complications which arose from COVID-19.

“On my end, the policy also requires a certain number of days’ notice before a hearing, or a certain number of days someone would have to respond to information,” Taylor added.

Taylor said the 60-day timeline is challenging. Salvemini said that this is the timeframe within which she strives to complete an investigation, but before the start of any university process, she tells the parties involved that the timeframe will be dependent on many factors and may exceed the 60-day timeframe.

Salvemini also noted that how often she speaks to the parties depends on the case.

“The frequency of communication with parties from the time that a report is received through the conclusion of any process varies,” she said.

Salvemini also clarified that her primary title is Equal Opportunity Compliance coordinator but is also designated as the Title IX coordinator. She is the only full time staff member who oversees these processes and responds to reports of sex discrimination.

“I am currently in the midst of the hiring process for a full-time staff member who will serve primarily as an investigator and will also assist with responding to reports received by my office,” she said.

This new staff member will help Salvmemini with her caseload, as she noted that the university recognizes the volume of reports received by her office has increased since she began working in her role in 2015.

Some individuals have concerns about the Title IX Office being housed within the Office of General Counsel, painting the perception of a conflict of interest. General Counsel serves as legal counsel for the university, the Board of Trustees, officers, colleges, and academic and administrative departments for Lehigh.

“Based on my observations and experience, the perception of a conflict of issue relating to this role tends to exist regardless of the reporting structure,” Salvemini said.

Taylor emphasized that much of Title IX policy is dictated by federal obligations, and the school tries to abide by the policy in a way that will be best for the student body.

“The committees which are tasked with keeping the policy updated are a group of people who all care deeply about the students that the policy will impact,” Taylor said.

Why does this matter?

Holona Ochs, an associate professor in the Political Science Department, said she has gone to the Title IX Office once on a student’s behalf, and she left feeling as though the process is flawed.

Ochs said those who report are not given enough information about how investigations and cases work, such as how the 60-day timeline is more of a suggestion rather than a federal mandate.

“Follow-up information doesn’t often include enough information or even any resources for them,” she said. “There are no mechanisms for restorative justice. Moreover, there are no apparent efforts at prevention based on problematic behaviors of repeat offenders or patterns of reporting. There are few reasons — if any — for people to trust the process as it stands.”

Ochs also questioned the office structures.

She feels that it’s contradictory to have a Title IX Office — which is supposed to be an advocate for students — housed within an office that generally has the institution’s best interest in mind.

“The process is set up to find reasons not to investigate,” Ochs said. “The predators get protected by Lehigh University’s counsel’s process.”

She said if legal counsel conducts an investigation following the letter of the law, the quality of the investigation doesn’t matter because they just have to prove they went through the motions.

Ochs believes that listing the Title IX Office under Lehigh’s General Counsel makes it more difficult for survivors to come forward as it would mean not just going after their assaulter, but also the university.

“You’re suing the predator and the institution,” Ochs said. “Then, you’re up against this goliath.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

4 Comments

Salvemini has shown repeatedly that she’s exactly as advertised: there to protect the university. The stories above make it clear that if you want anything to move through the university process with anything resembling speed and fairness, you need to lawyer up and make it plain that there are lawsuits and bad publicity in the offing if Karen drags her feet, then shrugs when you don’t bring in multiple-angle, time-and-date-stamped video of the guy raping you, with clear face shots and then probably a special PIV camera just to make sure, and says yeah, it’s a shame, there’s just not enough evidence.

Get a lawyer and get your parents involved. At schools that are more serious about holding rapists to account, you can report your rapist confidentally here: https://www.mycallisto.org/survivors#matching . The info is encrypted, and if multiple people report the same person, Callisto puts them in touch with a legal counselor to explore options. Karen’s repeatedly refused to discuss enrolling Lehigh in this service.

Actually it’d be amazing to be able to report Lehigh rapists retroactively. What a giant database that’d be. But I think we’d all like to know who got top hits. Would be awesome for commenting on those “Great job!” linkedin posts left by unwary winners.

Amy! Sign our petition! It includes that in the list of demands.

https://chng.it/sBrP7bTT4h

Signed. While I don’t agree with every demand in the petition, I think it’s the right direction, and the COI business is nuts. In the meantime, when I was talking with my daughter about this stuff earlier in the school year, she said she got why people were down on Clery notices, but that you could keep the same info on a dashboard that’d not only make it more accessible and also allow you to see patterns, including year-on-year and geographic, that the one-at-a-time emails don’t.