Medicaid continuous coverage, which was widely expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, will wind down in the coming months.

This signifies the largest transition in health coverage since the passing of the Affordable Care Act in March 2010.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services temporarily waived certain requirements for individuals to maintain coverage throughout the public health emergency. Now, eligibility will be reaccessed.

Health policy professor Michael Gusmano said around half a million people across Pennsylvania were able to receive Medicaid because of the pandemic.

States will be able to terminate Medicaid enrollment for individuals no longer eligible as soon as April 1 as a result of the Consolidated Appropriations Act. More information on key dates related to Medicaid continuous coverage can be found at medicaid.gov.

One issue, however, is the inevitability of eligible individuals’ removal from their coverage due to administrative errors.

“Moving out of the pandemic, moving out of the public health emergency rules, going back to the old way of doing business with Medicaid and allowing administrative complexity to boot people from a program they need and are eligible for is a move in the wrong direction,” Gusmano said.

Economics professor Chad Meyerhoefer said the process of unwinding Medicaid coverage was inevitable. While the program originally monitored the eligibility of participants, the pandemic made it fluctuate in unprecedented ways, and therefore, difficult to track.

Before coming to Lehigh, Meyerhoefer worked as a research economist at both the CNA Corporation — a federally funded security non-profit — and the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, familiarizing him with the subject of Medicaid. His research focuses broadly on the economics of health and nutrition.

While not unexpected to Meyerhoefer, he said the unwinding of Medicaid highlights problems with its enrollment recertification process.

Meyerhoefer said the recertification process varies widely between states, causing some individuals to be disproportionately impacted by the rollback.

In anticipation of these problems, the federal government has required each state to submit a plan for how they will handle this process.

In states that did not expand Medicaid coverage, Meyerhoefer said there will be people whose income level causes them to be too wealthy to qualify for Medicaid, yet too poor to qualify for subsidies under the Affordable Care Act.

“The most disadvantaged people sometimes have the hardest time either becoming enrolled or maintaining eligibility because they have difficulty complying with the administrative requirements,” Meyerhoefer said. “The particular worry here is that there is this huge backlog of cases that need to be evaluated.”

He said the volume increases the potential for administrative errors.

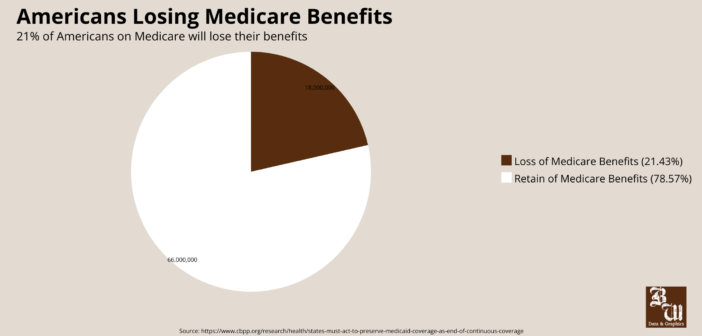

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “between five and 14 million people will lose Medicaid coverage when states ‘unwind’ the continuous enrollment provision this year.”

Meyerhoefer said individuals who were previously on Medicaid may be left behind simply due to difficulty in locating them, caused by the changing of addresses, phone numbers and other contact information held by various organizations.

Gusmano said the process known as “Medicaid churn,” where people get bumped off the program temporarily and then get back on, causes disruptions to their coverage and ability to access medical care and can lead to “devastating” results.

“It’s a frightening development for a lot of very vulnerable populations,” Gusmano said. “There is a real possibility that when the public health emergency ends in the coming months, statewide there could be thousands of people in the greater Lehigh Valley losing coverage.”

Meyerhoefer said strategies used to reduce the likelihood of truly eligible people being removed from the program include hiring more administrative workers, finding new ways to communicate with citizens and trying to expedite the recertification of people based on their age and disability status.

Meyerhoefer is confident Bethlehem will not be disproportionately impacted. Instead, he said he predicts Allentown to see more eligibility concerns due to the lower than average income of its residents.

Lehigh faculty continue to research the effectiveness of Medicaid to educate the public on the subject. Gusmano studied how requiring work documentation limits access to the program, advocating for universal healthcare.

“We have an obligation to share what we know so that policy has a chance to be grounded in fact and explicit arguments about policy goals,” Gusmano said. “We ought to be using this as an opportunity to force the conversation about what is problematic about how we make health insurance available for people.”

Meyerhoefer said having both Lehigh Valley Health Network and St. Luke’s Health Network in the area will help to mediate adverse consequences. Since Pennsylvania expanded Medicaid during the pandemic, the state will be able to focus on income-based eligibility, simplifying the process.

John Medalla and Kean Villanueva work as patient care partners within Lehigh Valley Health Network. They both said they think universal healthcare should be the standard, but its effectiveness can be brought into question.

“Depending on the degree of the healthcare and what is provided or how much treatment can be given, effectiveness can fluctuate,” Villanueva said.

Medalla agreed that the type of healthcare determines its effectiveness, regardless of one’s location.

“I believe it’s a gold standard that all countries should eventually have,” Medalla said.

Gusmano said he believes the United States should move away from the current healthcare model where sicker people pay higher premiums for insurance, and health insurance should not be tied to health status.

Meyerhoeffer agrees.

“We definitely could make this whole process easier if we could just agree as a society that everyone should have access to healthcare, and then think about how to make that happen,” Meyerhoefer said. “Let’s not worry so much about whether the country is moving towards nationalized health, and spend our energy creating a system that is both inclusive and effective.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.