The Bethlehem Area School District strives to give all students an equal opportunity to succeed, but researchers continue to see disturbing trends year after year when academic statistics like test scores and graduation rates are analyzed in terms of race and socioeconomic status.

The Bethlehem Area School District strives to give all students an equal opportunity to succeed, but researchers continue to see disturbing trends year after year when academic statistics like test scores and graduation rates are analyzed in terms of race and socioeconomic status.

The Latino/Hispanic population is one subdivision that struggles the most, and according to the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly one in three students enrolled in the school in the Bethlehem Area School District fall into that group.

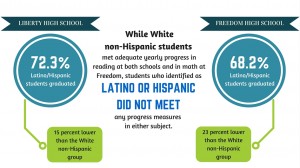

Data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education Adequate Yearly Progress report, commonly referred to as AYP, showed that neither Freedom nor Liberty High School, the two high schools in the Bethlehem Area School District, met the target AYP in 2011 or 2012. When assessed at a demographic level, it is clear that the Latino/Hispanic population is severely underperforming in relation to their peers.

AYP reports are a direct result of the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, an effort by the George W. Bush administration to even the standards in public schools. AYP is measured in terms of individual school and its subpopulations as well as by district. It calculates the final status of each school using a combination of graduation rates and test participation and scores from the assessment given during 11th grade.

While White non-Hispanic students met the AYP in reading at both schools and math at Freedom, students who identified as Latino or Hispanic did not meet any progress measures in either subject. The graduation rate for Latino/Hispanic students from Liberty High School in 2012 was 72.3 percent, about 15 percent lower than the White non-Hispanic group. At Freedom, the gap was even larger. Only 68.2 percent of Latino/Hispanic students graduated, which is more than 23 percent lower than the rate of their White non-Hispanic counterparts.

Despite efforts by the school district, academic success encompasses more than just money and resources. At the most basic level, the differentiating factor between successful and struggling students is deeply rooted in familial cultural understanding and standards of achievement.

Leigh Kuenne Rusnak, the administrator for high school special education in the Bethlehem Area School District, said teachers and researchers often talk about performance starting at home, but then wrongly assume that kids who don’t do well have parents who don’t love them or care about them. But this is nearly never the case. She said the first obstacle is defining success and the second is knowing how to access the system to make success a possibility.

“Knowing what success means for students and teaching them how to get it is part of our job, whether we like it or not,” said Vivian Robledo-Shorey, the supervisor for student and community engagement in the Bethlehem Area School District.

Robledo-Shorey and Kuenne Rusnak agreed that the vision of success in many Latino/Hispanic families is often drastically different than the traditional American dream. Families with limited education, English skills and outside support define success as a lower standard than a family well established to the American culture. As a result, many children of Hispanic origin are not exposed to the American version of attaining success by means of education and simply don’t realize that they can achieve more than their parents.

Neiad Ammary, an English teacher at Liberty High School, sees the consequences of this disconnection every day. He said in his experience it’s not normal for kids to achieve great academic or social outcomes without positive parental involvement. For example, just a few weeks ago he saw one student teaching another to roll a joint with a gum wrapper. After approaching the students and disciplining them by threatening to send them to the office where their parents would be called, one student simply looked at him and said, “I don’t care. My mom knows I smoke.”

From this experience, Ammary realized the enormous ripple effect of the parent on the child. Ultimately, he said, the biggest key to change will be educating the parents so they are aware of the opportunities their child can have if they are willing to strive for success.

Gabriela Velazquez, 14, a Liberty High School freshman, underlined Ammary’s point when she said parents are the biggest factor in determining a student’s success at school.

Kuenne Rusnak said an overwhelming majority of parents, regardless of race or income, want to see their children succeed. She explained that the issue that faces many Hispanic families is the lack of knowledge and understanding of the process that must be followed to achieve in this country. Lorna Velazquez, the executive director of the Hispanic Center Lehigh Valley, said that navigating a system in a new place is a skill in itself that is not inherent, contrary to popular belief in the American culture. Robledo-Shorey pointed out that if a parent does not know who to call, the right questions to ask or how to get their child help, that child is much more likely to fall behind.

The Hispanic population has a higher incidence of special needs in school, according to Kuenne Rusnak. She attributes this to the late start they usually get in school, not a lack of ability.

“All students start on the same place but as you see them struggle, academics start to effect behavior,” she said.

As students continue in school, their struggles compound and parental motivation lags, resulting in students beginning to miss assignments and stop participating. As self-confidence begins to waiver, these students’ experiences begin to differ more and more from those of their peers.

“Their meshing with traditional high school students becomes different,” Kuenne Rusnak said.

As students stray further from the path to high achievement, it becomes more difficult to pull them back, said Kuenne Rusnak and Robledo-Shorey. They said that the pathway for each student varies with their personal view of success and their self confidence in achieving that success.

“Do all students have access?” Kuenne Rusnak said, “Yes…in theory.”

The ability to recognize, understand and strive for success is the missing link for many Latino/Hispanic students. Despite having the same academic resources, equity doesn’t mean equality if the family support and experiential pieces don’t fit together at the right time for the right student. If any of these components are missing, academic success becomes a frustrating blind hunt for an intangible goal.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.