The gender-based violence spotlight often shines on sexual assault and rape, but in the background lurk other traumatic forms of abuse.

Obsessively checking a partner’s texts and emails each time they leave the room.

A drunken fight turned physical one night, but only one partner wakes up with bruises the next morning.

Threatening to kill the other if they leave the relationship after they said they’ve had enough.

Feeling like the beatings are deserved. Excusing it, because he said it would be the last time. Again.

From physical to emotional, acute to chronic, domestic violence isn’t limited to relationships with two partners living together.

Domestic and dating violence — now often referred to as intimate partner violence to encompass all relationships, be it casual or serious — happens on college campuses across the country.

It happens at Lehigh.

Brooke DeSipio, the director of the Office of Gender Violence Education and Support, defined intimate partner violence as abuse by a current or former partner in forms that include, but are not necessarily limited to, physical, sexual, emotional, verbal and financial abuse. The abuse might occur in one incident or over a course of time.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, intimate partner violence rates are highest among 18- to 24-year-olds — covering the general age of college students.

Based on data from the National Crime Victimization Survey, the bureau also reported that women suffer from intimate partner violence at a higher rate than men, with 82 percent of cases committed against women. Although DeSipio said men generally underreport abuse, possibly fearing it diminishes their masculinity.

Scott Burden, the associate director of the Pride Center, is a gender violence education advocate who works with students who might need support throughout the process of reporting an incident of abuse. He said bisexual women suffer higher rates of intimate partner violence, and often their abusers use their sexuality against them as a form of control.

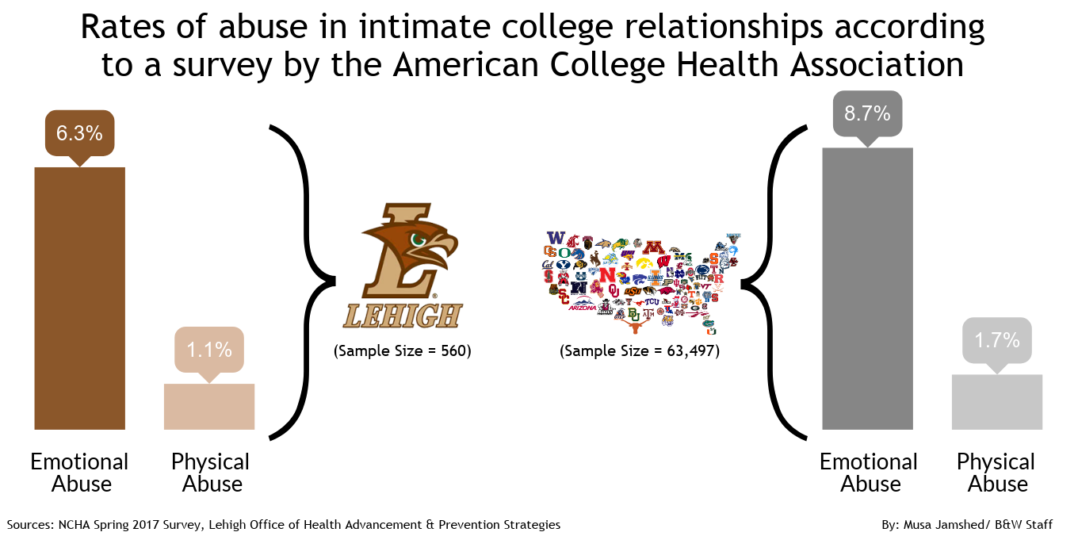

In a college health assessment issued to a randomly selected group of Lehigh students each year, out of 560 respondents in spring 2017, 6.3 percent reported experiencing an emotionally abusive relationship and 1.1 percent reported a physically abusive relationship. The national research survey reported 8.7 percent of students experienced emotional abuse and 1.7 percent experienced physical violence.

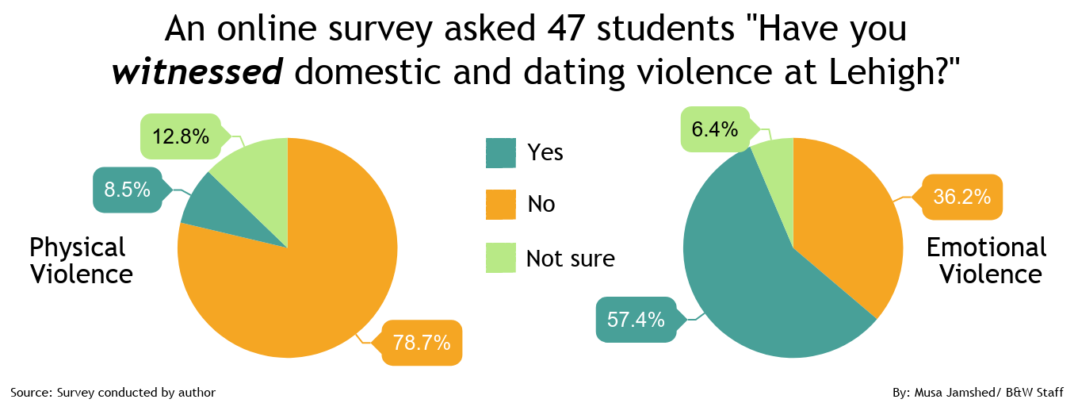

In a survey of 47 Lehigh students conducted by The Brown and White, four reported being a victim of physical abuse and nine reported being a victim of emotional abuse, with one answering that they were unsure if they had experienced abuse. All four students that experienced physical abuse while at Lehigh also reported being emotionally abused by their partner.

These 10 students who reported abuse or possible abuse were all female. Nine described their sexual orientation as heterosexual and one respondent was bisexual.

Nicole Johnson, an assistant professor in Lehigh’s counseling psychology program who has research background in intimate partner violence, said there can be a direct relationship between emotional and physical abuse.

“Often, abusers don’t tend to decide or focus on one — there tends to be all of these things coming together,” she said.

Johnson said one theory for why intimate partner violence is highest among college-aged victims is because college students often develop an “anything goes” mentality, acting in a way they wouldn’t if they were in “the real world.” She said the part of the brain that makes rational decisions doesn’t fully develop until a person is in their mid-20s, so young adults might not think about consequences before they act.

Abuse isn’t reserved only for committed relationships. In the Brown and White survey, one student anonymously reported being emotionally abused by her partner in a “hookup” relationship. She said he would repeatedly “shame” her and “put her down,” scolding her through text messages for telling her friends about their relationship and not acknowledging her “outside the bedroom.”

DeSipio said abuse happens in a cycle. The relationship starts in a “honeymoon phase” where the abusive partner makes the other feel loved. As tensions build, violence happens, and the cycle restarts as the abuser apologizes and promises it won’t happen again. The longer the relationship lasts, the shorter the cycle gets.

Another female student, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, fell into this cycle her freshman year.

He started physically abusing her when they were drunk and afterward he’d say he didn’t understand why it happened.

“It was always rationalized,” she said. “Each time was the last time, and I would genuinely believe it.”

DeSipio said abusive behavior is typically learned behavior for both the abuser — who might have grown up in an abusive household, for example — and the abused, who might have learned to expect abuse as part of a relationship.

As the abuse worsened over time, the student’s boyfriend blamed her because she wasn’t doing enough to keep him from hurting her, taking an emotional toll.

After about two years of dating off and on, she eventually escaped the relationship when an incident between her and her boyfriend required police intervention.

If it wasn’t for the police, the student said she might not have gotten out of the relationship.

“After the police got involved, it was out of my hands,” she said. “I hate to say it, but at first I was resistant to everyone saying it needed to be over because I was still rationalizing it, so as awful as that was, it needed to happen almost.”

DeSipio said it takes a survivor an average of seven to nine tries before they successfully leave an abusive relationship.

Johnson said victims might fear that leaving an abusive relationship is more dangerous than staying — for example, a partner might threaten to kill them for leaving. However, she said this is more often seen in partners who live together. She also said leaving an abusive relationship can be difficult because the abuser often controls their partner, separating them from others and becoming their only outlet of support.

According to the University of Michigan’s sexual assault prevention and awareness center, the small social atmosphere that a college campus creates can make it hard for victims of abuse to leave their relationship.

“On a college campus, you’re living in the same place, eating in the same place — everything is shared among the same people,” DeSipio said. “So, there are different challenges when offering safety and protection and resources to college students because of the nature of a college campus.”

However, DeSipio also said universities like Lehigh can provide students resources that the outside world can’t, including her office, free counseling and psychological services, and a Title IX coordinator.

Title IX states that a student cannot be discriminated against based on their sex. Under Title IX, measures such as class or dormitory changes can be made to protect a survivor of intimate partner violence from their perpetrator while allowing them to still have equal access to resources and opportunities on campus.

The most recent Title IX guidance issued in 2014 was rescinded in September 2017. However, since no new guidance has been put into place, DeSipio said Lehigh will continue to follow the old requirements, which requires universities to employ a Title IX coordinator whose role is to be neutral during an investigation.

“Title IX is not about survivor support, it’s about all students being treated fairly,” DeSipio said.

Lehigh’s Title IX coordinator, Karen Salvemini did not respond for comment.

The student survivor said Lehigh’s investigation process is separate from a criminal investigation, and a survivor can open a university investigation, request a no-contact order or do neither.

“The options aren’t that great, and it’s hard for them to place that in your hands,” the student said. “I think it’s great they have that in place, but I think it’s trickier than just having three options.”

She was glad, however, that Lehigh was able to keep her situation from becoming publicly known.

She said counseling services were also encouraged, and she attended sessions once a week before deciding to see a counselor off campus, who she still meets with regularly. She said making that decision made her feel more in control.

Her off-campus counseling center has allowed her to connect with other survivors through a support group, and she said talking with others who understand has helped.

“I would be lying if I said it didn’t cross my mind at least once a day,” she said. “I’ll always be a little different from other people.”

Those who have experienced intimate partner violence can reach out to the Office of Gender Violence Education and Support or Counseling and Psychological Services for support. The 24/7 on-call advocate can be reached at 610-758-4763.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

1 Comment

Pingback: Combating Intimate Partner Violence on Campuses – Vanderbilt Political Review