Every Wednesday morning at 7:45 a.m., 15 healthcare providers and coordinators gather for their weekly meeting, mapping out the schedule and tasks for the following days. They send appointment reminders to patients and follow up on referrals as their patients’ primary care doctors.

Except they don’t see their patients in an office or hospital. Instead, the Valley Health Partners Street Medicine team travels to see their patients at their homes or rotating clinics.

How it works

The health care practitioners visit encampments and homeless shelters during the week, providing care to people experiencing homelessness in Lehigh and Northampton counties. This is the same quality care that any traditional primary care office would provide, wherever their patients are most comfortable, said Bennie Eliason, the VHP Street Medicine program manager.

Eliason said the team does everything in their power to eliminate any transportation concerns, which is the No. 1 healthcare barrier their patients face.

If a patient doesn’t have a phone, she said the team members will visit them and give their patients an in-person reminder a day or two before their appointment.

Brett Feldman, the current director of USC Street Medicine, founded the program after he followed up with patients experiencing homelessness once a week, leading to a decrease in repeat emergency room visits.

On the days they are in the field, medical teams will meet up at the start spot, put on their packs, hike out to see the patient and administer the appointment, said Eric Rivers, the program’s clinical coordinator.

Another nurse team will run blood pressure checks, perform lab draws and glucose checks, and provide donated survival supplies. Rivers, who is also a registered nurse and previously worked in emergency medicine, said the general outreach team will also check on encampments and schedule appointments with current and new patients, while the behavioral health specialist facilitates individual therapy with patients.

The team includes Kate Dreisbach, a social worker and behavioral health specialist. She said their patients are some of the most kind and caring individuals she’s met.

“We get the honor of being allowed into their reality,” Eliason said.

She said teams consist of two to four people out of respect for patients, but sometimes the makeup of the team is incorrectly viewed as protection from the patients themselves.

However, she said they can’t blame patients for not trusting them as they have consistently been led down paths that lead to little to no change.

“A lot of time we have to rebuild those bridges, and that’s OK,” Eliason said.

She said the organization must give their patients time and attention to gain that trust, though it doesn’t happen overnight.

To receive social services, Eliason said patients have to have an up-to-date physiatric assessment. But to receive the assessment, patients normally have to wait several months for an appointment.

By meeting people where they are and providing psychosocial assessments, evaluating possible diagnoses and creating a treatment plan on the spot, Dreisbach breaks down many doors for their patients, Eliason said.

Dreisbach said once the patients have a diagnosis, they can be used to access Intensive Case Management services and housing services that need proof of mental illness to qualify for the programs.

“When you don’t have a phone (or) transportation and are in survival mode your first priority is not your appointments,” Dreisbach said. “By traveling to our patients, we go a step beyond showing their patients that we care, giving them hope.”

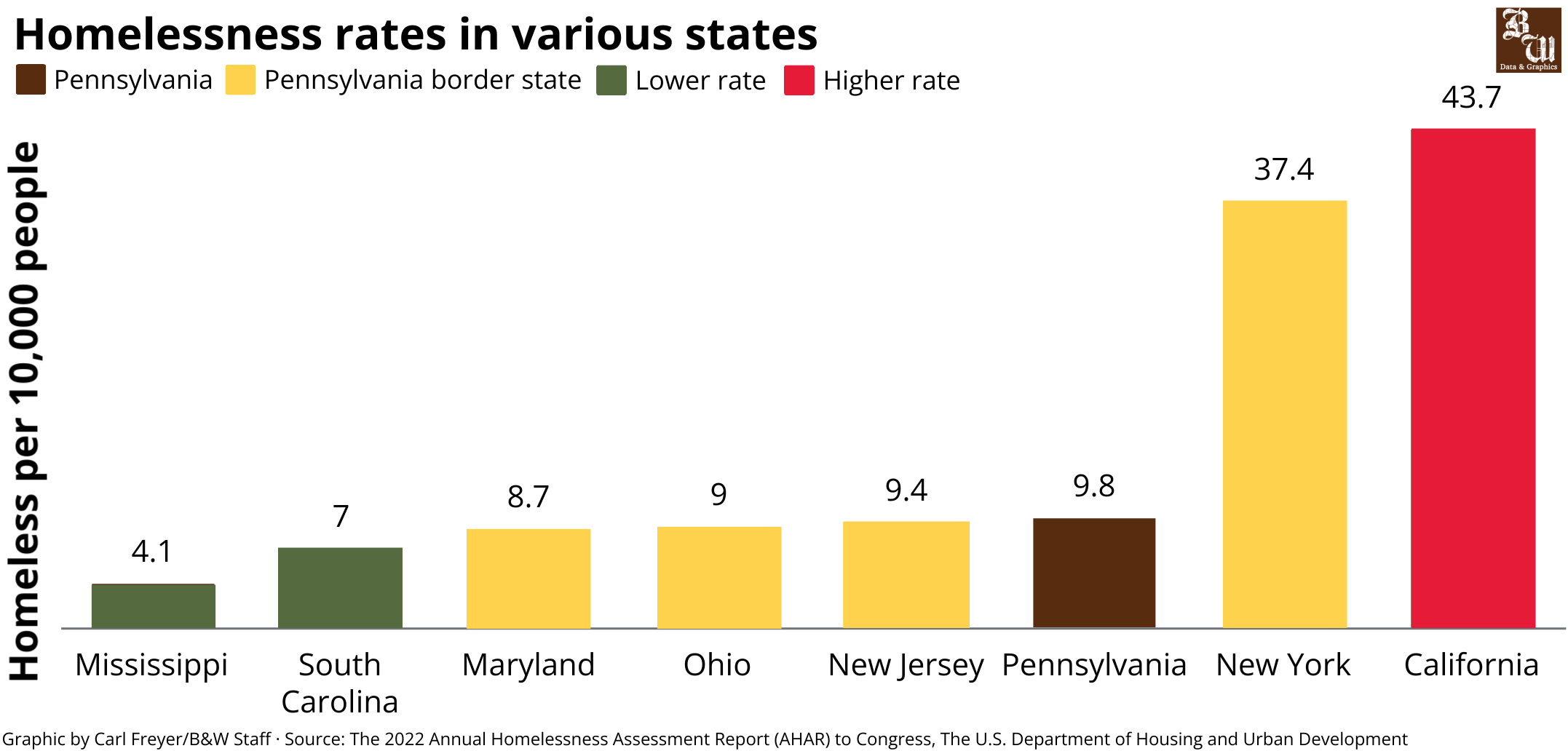

She says she wishes it was more commonly known that people are sometimes one illness, one mental health diagnosis or break, or one financial issue away from experiencing unstable housing.

“We are all fallible,” Dreisbach said.

The Valley Health Partners Street Medicine team is made up of 14 people. The team includes a clinical care coordinator, registered nurses, and physicians assistants. (Courtesy of Bennie Eliason)

Specific programs

The team requested donations for an autorefractor, a machine used for eye evaluations, in efforts to break down more barriers for their patients. This allowed them to provide 25 patients with eyeglasses since July.

Rivers remembers one of these patients putting on his new eyes for the first time and saying, “I can see! This is great!”

He said they can practice medicine and provide medication, but if their patients can’t see their medication bottles, they risk taking the wrong medication. So, providing glasses greatly improves the safety and quality of life for their patients.

Rivers said the team has also seen success in blood pressure treatment.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hypertension was a primary or contributing cause of 691,095 deaths in the United States in 2021.

Rivers said the team can provide blood pressure medication to patients who might not have been aware of their hypertension before the appointment.

Cancer, which is the second leading cause of death in the U.S., is extremely difficult to treat when experiencing homelessness, he said, especially because patients are required to have a safe place to recover once they are discharged to receive surgery.

VHP Street Medicine’s respite program, which is a philanthropically funded program that provides a place for patients to stay for a few days after treatment, works to eliminate this barrier.

For patients who have lower extremity wounds, Rivers said the team will also travel to patients daily for dressing changes, which allows sometimes month-old wounds to start healing within a week.

He said a certified recovery specialist on the team will also work with patients struggling with alcohol or other substance use addiction by talking with them about treatment and recovery options.

If any of their patients end up incarcerated, Rivers said that VHP Street Medicine’s criminal justice navigator will visit the prison to meet with patients and develop a plan once they are released to ensure they don’t go without medication.

“We have seen patients at 7 a.m. in the parking lot of the prison (when they’re released),” Rivers said, “so they can have the best success rate possible.”

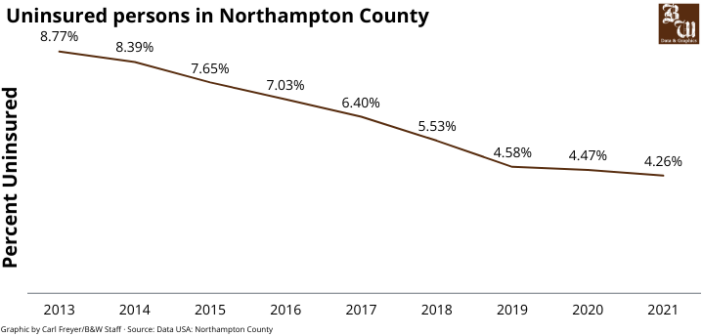

As a Federally Qualified Health Center Look-Alike, Eliason said VHP Street Medicine provides medical care to individuals regardless of their ability to pay and their immigration status.

If a patient doesn’t have benefits or needs their plan transferred to a different county, the community health care worker on the team can set that up for them, allowing them to receive state benefits like food stamps.

The team also updates medical charts in the field to provide continuity of care, so if the patient ends up in the emergency room, Eliason said their medical history is up to date.

“After the end of the eviction moratorium (after the COVID-19 pandemic), VHP Street Medicine saw an influx of 30 to 40 patients a month, a statistic which has not slowed down,” Eliason said. “While we are not 911, we never turn away anyone who needs care.”

Rivers said their department will take the time it needs for a visit, whether it’s 10 minutes to an hour, allowing them to understand what they can for the patient.

A full list of VHP Street Medicine rotational clinics can be found on their website. To get in contact with the team or to make an appointment, people can call 484-268-0755.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.