Luke Martin owns three single-family row houses, all constructed in 1900, on South Bethlehem’s Montclair Avenue.

Martin, a managing partner of B&L properties, which rents properties to around 750 students in Pennsylvania, said when he purchased these houses, he was immediately struck by their age.

Shortly after acquiring 421 Montclair Ave., Martin gutted the property, stripping it down to the wooden framing of its walls, ceilings and floors.

With only the structural framework intact, he installed new wiring, plumbing, insulation, drywall, windows, flooring and hot water heaters.

When he purchased 431 and 433 Montclair Ave., he, once again, completed a full-scale remodel.

“We wanted to make sure our houses were well-maintained and clean and safe,” Martin said. “The older a property gets, the more expensive and difficult maintenance becomes. These houses are much easier to maintain now, because they’re essentially new.”

The median age of Bethlehem homes is 70 years, roughly 12 years older than the state average, according to the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Study. Sara Satullo, the city’s deputy director of community development, said Bethlehem’s aging housing stock is contributing to the city’s housing crisis by burdening homeowners and threatening their physical and financial well-being.

Older homes often pose health risks, such as mold and lead — assumed present in all homes built before 1978, according to the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency — and safety concerns, like structural instability or inadequate weatherization.

These houses can also be energy inefficient and require frequent maintenance, resulting in high, ongoing costs. Fully addressing these issues can be prohibitively expensive, as Martin’s updates each cost more than $30,000.

In a city where 18% of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the United States Census Bureau, many homeowners lack the financial resources to maintain or remodel their homes.

If left unaddressed, maintenance problems can lead to serious injuries, such as lead poisoning or hypothermia, and render a house uninhabitable, displacing its residents, according to the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative.

As the city grapples with a growing housing crisis, characterized by deteriorating housing conditions, limited affordable housing options and rising housing costs, Community Action Lehigh Valley has developed a holistic response.

Community Action Lehigh Valley is a branch of the National Community Action Partnership, a network of over 1,000 agencies dedicated to combating poverty by mobilizing communities to address its conditions and causes.

The Lehigh Valley chapter operates programs across six key areas, including its housing coalition — Community Action Homes — which focuses on improving the quality of affordable housing through a comprehensive strategy.

Chuck Weiss, the associate executive director of Community Action Homes, said designing this strategy required an understanding of the local drivers of the housing crisis — age of housing stock, limited land for development and increasing demand.

“In Bethlehem, we have a land problem,” Weiss said. “There’s very little left to build on.”

Satullo said this is because Bethlehem is a historic city. She said the majority of the land was developed in the 1900s to meet the needs of the region’s thriving steel and textile industries.

This has left just 2.2% of vacant residential land in the city of Bethlehem available for development, Satullo said.

A Forbes analysis of the 35 largest U.S. cities found the percentage of available land for development to be inversely proportional to home values.

“That limited land goes at a very exorbitant price, so you end up getting very expensive houses being built, and there’s nothing left for middle and low-income people,” Weiss said.

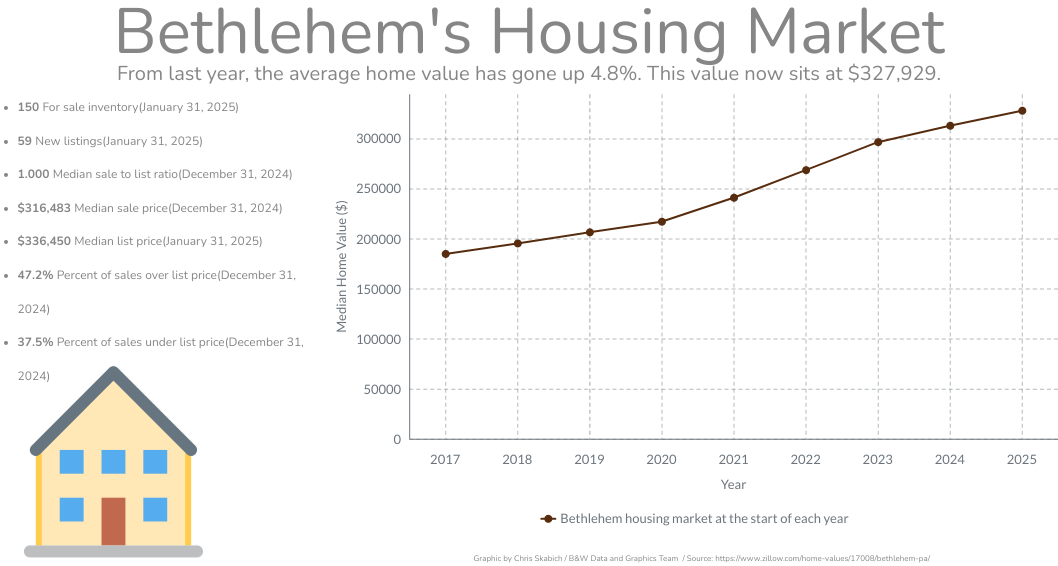

The average home value in Bethlehem is $328,916, which is affordable for less than 30% of the city’s population, according to its strategy to build housing security.

In 2023, the Census Bureau reported there were 33,248 housing units in Bethlehem. Over 98% were occupied, resulting in a vacancy rate of 1.4%, according to the American Community Survey.

Weiss said a healthy vacancy rate — essential for ensuring affordability, market stability and economic mobility — is around 8%.

The housing market pressures in Bethlehem have been exacerbated by an influx of people moving to the city. Since 2020, according to the Census Bureau, the population has grown by about 3,000 residents, partly driven by the COVID pandemic-era migration shift.

In this same period of time, Bethlehem’s median home sale price increased by 49.18%, according to Zillow.

“I was surprised by the speed and the amount that prices went up,” Martin said. “When we bought properties in Bethlehem, we were expecting the value to go up some, but since COVID, they’ve gone up way more than that.”

Weiss said he’s seen the housing crisis skyrocket since the start of the COVID pandemic.

“The housing situation is so desperate now that we’re always trying to develop new programs and partnerships to address it,” he said.

Community Action’s programs include the construction, acquisition and rehabilitation of homes, as well as housing counseling and weatherization services, like energy and heating assistance.

From 2023 to 2024, Community Action sold one house, managed the renovation of two properties, completed 11 facade improvements, coordinated rehabilitation for 40 homes through the Whole-Home Repairs Program, counseled over 200 homeowners and completed over 600 weatherization jobs, according to its annual report.

To qualify for these programs, participants must own a home in Northampton or Lehigh County and meet income eligibility requirements, which vary by program.

“If they’re calling us, life is bad,” Weiss said. “We do everything we can to help them turn it around.”

Mike Austin, the director of weatherization at Community Action Homes, said homeowners either seek out its services independently or are referred through the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program — a funding benefit administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Austin said this program has a substantial waitlist, as demand significantly outpaces Community Action’s service capacity.

Program applicants are assigned a hardship number based on their circumstances, and those with the greatest need receive priority assistance.

“Someone that might not have as much hardship as somebody else can keep getting bumped, because we just grab the people with the most need,” Austin said. “But we do try to service everybody we can.”

Applicants to other initiatives, like the Whole-Home Repairs program, are processed on a first-come, first-serve basis.

In 2022, the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development launched the COVID-19 ARPA Whole-Home Repairs Program. This allocated $125 million in federal pandemic relief to county-wide organizations to address safety and habitability.

In Lehigh County, Community Action was selected to receive $2.7 million in funding, which it would redistribute to homeowners as home improvement grants.

Community Action Homes launched its application in May 2023 with 60 slots for homes — 30 went to homeowners on a waitlist, and the remaining 30 opened to new applicants.

Weiss said he watched as the slots filled up in just two hours and then grimaced as 500 more requests came in throughout the day.

By the end of the following week, 2,500 additional requests joined the waitlist.

According to their webpage, as of Feb. 25, 2025, the organization is not taking new applicants as they serve current customers.

Community Action Homes frequently sees overflowing waitlists for its programs due to limited financial resources, which hinder the agency from meeting the needs of all Bethlehem residents seeking its services.

In November 2023, the city of Bethlehem completed a year-long exhaustive housing strategy research project, resulting in a five-year strategic plan titled “Opening Doors: Strategies to Build Housing Stability in Bethlehem.”

The plan recognized Community Action as a contributor in addressing the housing crisis through initiatives like Whole-Home Repairs, facade improvements and housing counseling.

It also highlighted the overwhelming unmet demand for these programs.

Weiss said he knows the agency alone cannot solve a crisis affecting the entire city, but the days when he can transform even one person’s life make his work meaningful.

One such day, while working on a house in Allentown, he received a call about a heating system failure at a nearby house whose owner was enrolled in the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program.

Weiss saw one of the agency’s contractors arrive at the house and followed him inside. While the contractor worked on the heater, Weiss walked through the home.

“It was a woman and her two children,” Weiss said. “There was no food in the house, the roof was leaking and their windows were busted.”

Through Community Action’s connections, Weiss arranged for food to be delivered to the family. He also had their roof and windows replaced and set up a payment plan to help them catch up on their taxes.

The woman was earning $7.25 an hour at a local warehouse, so Community Action helped her secure a job paying $17 an hour.

Weiss said her life was turned around in the span of two weeks. After a little help, she excelled, which he said is common in the stories the agency sees.

“There’s a definite feel-good factor when you can change people’s lives by giving them a hand up, not a handout, and watch their lives turn around,” Weiss said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

1 Comment

Luke Martin is a part of the problem with affordable housing as out of state companies buy up existing inventory & turn them into student housing for exhorbitant rental fees.

These homes were homes for residents that essentially have been taken out of the inventory for transient rentals.

This practice coupled with Airbnb purchasers doing the same thing is a huge part of the problem in all major cities.

Bethlehem has a zoning ordinance that prohibits this practice in most neighborhoods but elects not to enforce their own codes.

Grace Crampsie Smith from City Council is running for Mayor in May primary against existing Mayor & this is a major part of her agenda to preserve neighborhoods in Bethlehem.

She is our only hope to solve this problem