As a private institution — much like other private organizations and corporations — Lehigh is not strictly bound by First Amendment rights.

Still, in the Policy of Freedom of Thought, Inquiry and Expression, and Dissent by Students, the institution makes statements supporting students’ rights to express themselves as long as certain parameters are followed.

However, students, faculty and Lehigh Valley community members started to question Lehigh’s policies related to free speech principles following a rally held by the Lehigh Student Political Action Coalition (SPAC) to stand in solidarity with Palestine.

At the center of this concern, SPAC and three Lehigh Valley residents shared documents and statements with The Brown and White that call into question free expression at Lehigh.

Starting April 29, 2024, SPAC hosted Palestine Solidarity Week, during which the group held different events each day of the week on Lehigh’s front lawn. On May 3, 2024, SPAC held a culminating rally.

On the day of the rally, approximately 300 people marched together from the front lawn to East Morton Street, turning onto Webster Street and stopping on West Packer Avenue.

West Packer Avenue was closed for approximately two hours while attendees gathered in the intersection, making speeches and chanting their requests of the institutions and companies in the area. The closure was not planned, and traffic was blocked.

The requests for Lehigh included: to call for an immediate and permanent ceasefire, to disclose financial investments, to divest from Israel, and to uphold its right to freedom of speech.

Lehigh’s Policy on Freedom of Thought, Inquiry and Expression, and Dissent states, “students and student organizations are free to discuss all topics and questions of interest to them and to express opinions publicly and privately.”

According to the policy, students also have the freedom to hold a demonstration on campus as an expression of support or dissent as long as they abide by the rules, policies and procedures laid out in the Student Code of Conduct.

Toward the end of the summer, Ciaran Buitrago, ‘25, president of the SPAC, said administration contacted the club and cited them for violating two principles, Respect for Community E and Respect for Community I, outlined in the Student Code of Conduct.

Respect for Community E is outlined as “failure to comply with the reasonable requests of University officials (including law enforcement) while acting in the performance of their duties.”

Respect for Community I refers to “violating any Lehigh University policies, rules or regulations, including but not limited to, residential living policies (General Provisions for Occupancy) and policies related to the use of the University computer network.”

Community warning

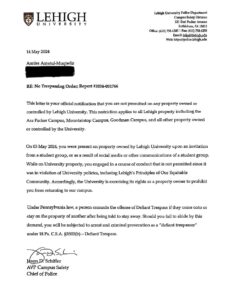

Meanwhile, five Muslim Lehigh Valley residents were delivered letters through certified mail, signed by Jason Schiffer, chief of the Lehigh University Police Department, stating they were no longer “permitted on any property owned or controlled by Lehigh University.” Three residents shared a copy of their letters with The Brown and White.

The letter is a No Trespassing Order, which further states the individuals “engaged in a course of conduct that is not permitted since it was in violation of University policies, including Lehigh’s Principles of Our Equitable Community.”

Following Palestine Solidarity Week, five Muslim Lehigh Valley community members were banned from Lehigh’s campus. Pictured above is the No Trespassing Order Eastern resident An-Nisa Amatul received from the Lehigh University Police Department on May 14, 2024. (Courtesy of An-Nisa Amatul)

Schiffer has not directly responded to numerous requests for comment regarding the letters.

LUPD business manager Ashley Strause said in an email, “Given the sensitive nature of the subject matter, Jason (Schiffer) has requested to review specific questions in advance of the interview.”

In this instance, The Brown and White elected to share 10 questions over email but did not receive a response. The last request for comment was made March 17, and no response was received.

Mubashar Mughal, an Allentown resident who is Muslim, received a letter. He said the vague language concerned him.

“They didn’t specify exactly what policy we violated or how we violated it,” Mughal said.

The letter states Lehigh has decided to exercise its right as a property owner to prohibit the receivers from returning to campus.

Under Lehigh’s Policy on Freedom of Thought, Inquiry and Expression, and Dissent by Students, it’s stated “persons or groups who are not part of the University community have no right or privilege to demonstrate, protest, post or solicit on University property.”

This said, the same policy outlines that outside community members can be present and protest on campus if they are invited by a university-recognized student organization or by a Lehigh faculty or staff member for a legitimate educational purpose.

The policy further states, “If invitation or sponsorship is extended, it is subject to the compliance of such person or group with all University rules, policies, and procedures, and applicable legal requirements. Failure of a person or group on University property to adhere to an official request to leave University property may result in arrest or removal for trespassing.”

Buitrago said the community members were invited to the march by SPAC.

“We were collaborators, and they were included along the whole process,” he said.

Buitrago said he is not aware of an official process clubs have to go through when inviting outside community members. He said he does know, however, that when scheduling an event, the club can specify if it’s closed to Lehigh ID holders.

“Most events on campus are, by default, open to everyone, but you can specify it’s closed, and our event was certainly not closed,” Buitrago said. “We encouraged and invited community members.”

An-Nisa Amatul, an Easton resident who is Muslim, also received a letter.

Amatul said she was surprised when she read the letter and began asking other attendees if they received the same notice.

Out of the 100 attendees not affiliated with Lehigh who have been contacted, she said she has yet to hear of anyone else who has been banned from campus following the march.

Amatul said the five people who were banned are not aware of how they were identified or why they specifically received letters.

The No Trespassing Order states, under Pennsylvania law 18 Pa. C.S.A. §3503(b), a person commits the offense of Defiant Trespass if they come onto or stay on the property of another after being told to stay away.

The letter closes with the statement, “Should you fail to abide by this demand, you will be subjected to arrest and criminal prosecution as a ‘defiant trespasser.’”

Amatul said her biggest concern is the lack of clarification about what Lehigh’s property is.

“So many things are owned by Lehigh University, and I feel like the language in the letter was very specific and very targeted — saying basically, ‘We don’t want you a part of anything that has to be near us,’” Amatul said.

For those who reside in the Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton area, Amatul said, these restrictions are unfair, even for those who live in neighboring cities, as so much property is owned by the institution.

“Coming up on a year since the ban, there’ve been many community events I’ve not been able to attend because they’re considered to be on Lehigh’s property (or) at Lehigh,” she said. “And out of restrictions (and) safety concerns, I haven’t gone.”

Many universities, including Lehigh, own land and property outside of their campuses. However, according to Pennsylvania’s Office of Open Records, private universities are not subject to the Right-To-Know-Law. This includes open-record laws, meaning a private institution, such as Lehigh, is not obligated to disclose property ownership, along with other financial information.

Since the No Trespassing Order does not outline what does and does not include Lehigh’s property — across its four campuses that make up 2,355 acres — Amatul said she has had to remain careful.

“I’m already being hyper-vigilant enough, just because of the world that we live in and how it treats Muslim women, but even more so now,” Amatul said. “It’s very threatening, and it’s also very concerning that they have the power to do that in the first place, because you shouldn’t have to feel that way, and where you live.”

Being a long-time resident of the area, Amatul said she plans to continue fighting the ban.

“You’re barring people from such a large area of where they live, where they reside,” Amatul said. “I went to school right across the bridge, and we visited Lehigh’s campus frequently.”

Mughal said he personally did not speak at the march. He said the five of them have tried to find out if another individual had said or done something that they, as a group, would not condone. He said they have not found anything alarming.

“We’re not there to harm anybody,” Mughal said. “We’re not there to cause a riot or create a hostile environment for anybody. We’re there to speak for justice, equal rights and humanity.”

Prior to receiving his letter, Mughal said he noticed LUPD’s Instagram account had been viewing his stories and liked one of his older posts, suggesting they might have been viewing his social media accounts to find his personal information.

Being frequent organizers and relatively public people, some of the individuals said they were not shocked Lehigh found their personal information.

However, Allison Mickel, an anthropology professor at Lehigh who often works with SPAC, said two of the banned individuals had never taken part in any organizing and were not involved in planning the march.

“One of them had never attended a protest or rally before in their life and was driving a rental car that day and goes by, publicly, a name that’s not their government name, which raises questions about how they were identified and how their home was identified,” Mickel said.

The five individuals got in touch with Mickel and CAIR Philadelphia, a grassroots civil rights and advocacy group.

“Legally, Lehigh, as a private landowner, has the right to charge anyone with trespass that they technically want to, but we should all be really concerned,” Mickel said.

Given every individual banned from Lehigh’s property is Muslim, Mickel said it seemed like an intentional decision made by the university.

Raya Abdelaal, a Bethlehem resident who received a letter, said with the help of Mickel and CAIR, the group reached out to Schiffer to further discuss the legal actions taken against them.

She said Schiffer suggested they meet at the police station, which worried the group, as the station is a part of Lehigh’s property.

“You told us we were banned, so why would we go somewhere we were banned from?” Abdelaal said. “We kept going back and forth. We asked if we can please meet in a neutral zone so we can make sure everybody feels safe, and they declined.”

After a neutral location was not agreed upon, Mickel said Schiffer stopped responding to her and CAIR Philadelphia, and she has not reached out since June 2024.

Abdelaal said she believes Lehigh will take the angle that their actions during the rally were anti-semitic; however, she said what they’re fighting for is not anti-semitic.

“I think the students at Lehigh are entitled to protest,” Abdelaal said. “Things that their university has participated in, in my opinion, is complicit in what is going on in Israel, whether they want it or not, we know that they have ties to Israel.”

More on the Student Political Action Coalition’s disciplinary hearing

As for SPAC, the specific details that led to the disciplinary charges are unclear.

The Brown and White reached out to Emily Collins, a media relations specialist for University Communications and Public Affairs, and had an email exchange in November 2024. She stated in an email that administration cannot answer specific questions regarding individual disciplinary actions due to confidentiality requirements.

Buitrago said he was one of the witnesses called for the hearing. Prior to the march, he said, the club filled out a student affairs event registration form and a demonstration registration form.

He said the demonstration registration form described the details of the march, with a map of where it would take place, which was emailed directly to the associate director of student involvement and student center operations. He said the university later denied the request due to not having adequate police resources to ensure safety.

The club then met with the associate director to discuss the event. Buitrago said he reiterated that people were coming to march, and it was infeasible to cancel on such short notice.

However, Buitrago said he assured the administration that SPAC would ensure everyone’s safety.

“We wanted to get as much approval as we could in the short amount of time, so we decided to submit another form,” Buitrago said.

With three days remaining until the scheduled event, Buitrago said he filled out a second form that did not outline details of a march.

Alongside the form, he said he emailed Student Affairs explaining that SPAC would not declare a march, but with the number of people who planned to attend, the club could not control whether or not a march would happen.

“Basically, we said, ‘Be warned, it will probably happen anyways, even though it’s not been officially approved,’” Buitrago said.

He said the second event form was then approved by the university.

LUPD officers and members of Lehigh administration were present at the event.

Buitrago said there was no communication or effort made by them to stop the march, which led student organizers to assume their actions were condoned.

He said part of the reason SPAC was in trouble was due to disrupting traffic.

Packard Avenue is property of the City of Bethlehem, not Lehigh. To block off the street legally, the club would need approval from the Bethlehem Police Department.

During the march, LUPD blocked Packer Avenue. However, Buitrago said no requests were made by SPAC to close the street.

“No one was in danger, nothing unsafe happened, and no one told us to stop marching,” Buitrago said.

Lehigh’s Policy on Freedom of Thought, Inquiry and Expression, and Dissent by Students states students’ right to free speech and expression does not include activity that “Materially disrupts or obstructs the functions of the University or imminently threatens such disruption or obstruction.”

The Brown and White spoke with Ziad Munson, a sociology professor at Lehigh, in October following a Campus Voices he wrote on free expression and the actions taken by the university following SPAC’s May 2024 protest. He said while there is evidence the student coalition violated certain policies, they seemed to be relatively minor violations that occur with regularity in other contexts.

In his Campus Voices, Munson wrote about the Marching 97 and the Lehigh-Lafayette Rivalry.

The long-held tradition entails the band marching around across campus, entering buildings and disrupting classes to play their instruments in the days leading up to the rivalry game.

Munson said he loves the tradition, but one cannot argue it isn’t disruptive. In comparison, one cannot argue that SPAC didn’t disrupt traffic, but he said there are times when the community accepts certain events are more important than the rules.

“I think the Marching 97 and school spirit in that context is one of those,” Munson said. “Student speech about one of the major conflicts in the world, one in which tens of thousands are being killed, is worthy of being heard, and that’s where I think Lehigh fell down. Lehigh is not applying rules equally in equal situations.”

Mickel said she is disturbed by the precedent in which student organizations are punished for protesting, as it’s a cornerstone for democracy. She said she is also concerned about the vagueness of the charges.

“We teach in so many of our classes that it’s actually necessary to disobey things that are unethical and to disrupt sometimes,” Mickel said. “And so for Lehigh to say no one was harmed, nothing got damaged, but this was out of line with the principles of our community, it doesn’t feel right.”

As a result of the hearing, SPAC was let off with a warning and two stipulations.

Buitrago said the first stipulation was a mandatory meeting with the associate director of Student Involvement and members of SPAC’s executive board.

“That meeting was essentially just talking about how (SPAC) can be better at organizing and making sure communication with the university administration is clear,” Buitrago said.

He said it was a friendly meeting, going over how the club can be better at conducting activism.

Buitrago said the second stipulation is a meeting with the Office of General Counsel, which 85% of the rostered members are expected to attend. He said this has yet to occur.

Buitrago said the last time he heard of this meeting was during a discussion he had with Christopher Mulvihill, the associate dean of students.

He said Mulvihill asked for potential topics the student coalition would like to cover during the meeting. One which Buitrago suggested was the Campus Voices written by Munson.

“I imagine that he looked through it, and I haven’t heard anything about this meeting with general counsel since,” Buitrago said.

The future of the Student Political Action Coalition

Buitrago said he isn’t worried about the future of SPAC and its ability to continue organizing.

He said in terms of the conduct case, panelists told him the club plays an important role on campus as social justice advocates, expressing appreciation for the compassion and support it provides to the university community. Additionally, he said they commended their commitment to fostering a strong, positive relationship between SPAC, LUPD and the broader university administration.

“I thought it was generally a friendly attitude, and the panelists were just doing their job,” Buitrago said. “I think the more important issue is, ‘Why did the trial happen at all?’”

Buitrago said one of the problems he has with the situation is the inconsistent application of rules.

In November 2023, the student coalition held a similar protest to the one held last May.

Buitrago said attendees marched from the STEPS lawn to the flagpole on the front lawn with hundreds of people and blocked off Packer Avenue for a significant period of time.

He said LUPD and administrators were present at the November 2023 protest, and there were no repercussions.

“Lehigh’s administration had kind of unrealistic expectations for us,” Buitrago said. “We tried our best to play by their rules, but if even we can’t play by their rules, then no one can in terms of activism.”

Buitrago said SPAC has continued to hold events, and they hope to do more in the upcoming semesters.

At the same time, he said the club has not held another protest since, as they’ve felt discouraged by the university ignoring the purpose of their activism overall.

“It was very discouraging to see that the university is very quick to punish students for sharing their voices but didn’t meet any of our demands in terms of stopping the violence in Gaza and normalizing the violence perpetuated by Israel,” Buitrago said.

Despite this, since the beginning of the spring semester, Buitrago said the club has continued to organize events since the hearing, such as a Vigil for Palestine, multiple trips to City Hall to advocate for the protection of groups targeted by President Donald Trump’s administration and educational events attended by hundreds of people.

The future of free expression at Lehigh

Munson said free expression is a foundational value in higher education, as it’s the basis of Lehigh’s central mission.

According to Lehigh’s mission statement, the goal is “to advance learning the integration of teaching, research and service to others.”

Munson said in terms of research and teaching, it’s difficult to discover and develop novel or creative ideas if you have to censor yourself due to concerns of what people in power may say or do.

“Higher education is unique in that nowhere else is there a place where anyone is claiming that you should be able to speak your mind freely and not be sanctioned for it in an official way,” Munson said.

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization defending the rights to free speech and free thought, recently released their 2024 College Free Speech Rankings.

Lehigh was ranked 148 out of 248 schools, naming the school slightly below average on upholding free speech.

On Lehigh’s FIRE profile, the speech code rating is red, which indicates the university has at least one policy that both clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech.

Specifically, sections 2.2 and 2.2.1 of Lehigh’s Policy on Harassment and Non-Discrimination have been flagged.

When asked about the concerns students and community members have on policies having arbitrary application, Collins wrote in an email that Lehigh’s primary responsibility is always the safety and security of students, faculty and staff.

“It is our expectation that they behave in a manner that supports campus safety and aligns with the Principles of Our Equitable Community,” Collins wrote. “Lehigh, as a private institution, has the right to limit speech and expression when it contradicts the mission of the university and the values of the community.”

Buitrago said he doesn’t believe the reason SPAC was brought to a disciplinary hearing was due to safety concerns. He said if they were concerned about campus safety during the march, LUPD or members of administration would have asked them to disperse.

“The conduct case is not about campus safety, it’s not about the code of conduct,” Buitrago said. “It’s about punishing students for trying to stand for what’s right and trying to use their voices as activists.”

Munson said the value of freedom of expression needs to apply to everyone equally, but context still matters.

Hypothetically speaking, he said if there were 1,000 people on campus yelling derogatory terms toward students of specific identity groups, that would be a different conversation.

In the situation of people sharing their beliefs on the war in the Middle East, Munson said it’s a national issue students and community members should be able to speak on.

Collins wrote in an email that Lehigh continues to work with student groups and faculty to ensure events are held in ways that are consistent with their policies for peaceful, respectful free expression.

“In polarized times, dialogue is more important than ever,” Collins wrote. “We see the current global and national events as opportunities to continue to cultivate an environment that fosters openness, debate and curiosity about diverse perspectives. By seeking and hearing a range of perspectives we can continue to build a community where every member feels welcome, supported, and valued, and where every person knows they belong and feels safe.”

Collins said a committee of faculty, staff and students met last semester to review Lehigh’s policies of free expression.

She said the committee recommended Lehigh adopt the Chicago Principles, which support free expression, along with a Lehigh-specific preamble that places it in the context of other guidance, including the Principles of Our Equitable Community.

The Chicago Principles were created and enforced at The University of Chicago in 2014, affirming commitment to free expression. According to the FIRE Organization, the model has since been officially adopted or endorsed by 111 institutions and faculty bodies.

Collins said the final piece of implementing the Chicago Principles is underway, which includes releasing the committee report to administration, recommending the adoption.

“Decisions are not made unilaterally and leaders across the university are consulted before decisions are made,” Collins wrote. “The Lehigh community has always operated in ways that are respectful of a range of views on any issue and the recent events hosted on campus continue to illustrate these values.”

Munson said he acknowledges the world is more polarized than ever, and operating a university is complicated. He said there is not one right or wrong answer to address issues related to free speech and expression.

However, he said he believes the first principle universities should always think about is how decisions impact free expression.

“How can we make sure the most diverse, most varied number of voices are heard, with particular attention to voices coming from those that aren’t typically in power?” Munson said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

2 Comments

Excellent reporting. Lehigh (and universities in general) have no consistent principles. They can have their silly code of conduct and vague policies that celebrate “making students’ voices heard” and “freedom of expression” – or some other garbage like that. But at the end of the day, it’s all about public relations and risk management.

The university will not uphold any free speech principles if the speech in question presents a risk to their reputation.

I’d like to say that’s fine. They’re a private institution, they can decide what happens on their property.

But it’s not that simple. Not only because their own policies state otherwise, but because universities hold a very special place in our world. If one place was to exist outside the bounds of property law, reputation management, and finance, where you would hope students could explore and express their ideas (provided they’re not harming others) without prejudice, it would be at a university.

Not only is this action inconsistent with Lehigh’s own stated policies, but inconsistent with the university’s place in the western world as bastions of free speech and exploration. This is no surprise, but is still worth mentioning how far we’ve fallen.

It also crosses into dangerous territory if any of these students are facing disciplinary action. Having their education destroyed, tuition money gone, futures severely negatively impacted, all for expressing their opinion, would be outrageous.

This would certainly call into question whether I want my kids attending the university in the future.

As Lehigh continues to suppress student activism and political speech, the genocide in Gaza is at its worst moment yet. Millions of Palestinians face starvation and lack housing, clean water, and medicine. Israel’s military enacts targeted killings of doctors, journalists, and children. What good is our supposed freedom of expression if it can’t be used to call for the end of this American-backed atrocity?

https://www.dropsitenews.com/p/total-siege-starvation-displacement-gaza-city