For the unbeatable price of just $240,000, you can be the proud owner of six 2.5-carat Tiffany diamond engagement rings. Or rent a mid-priced Manhattan studio apartment for eight and a half years. Or buy a 2015 Bentley Continental GT — and have a cool $10,000 to spare.

Or, of course, you can be the recipient of a Lehigh bachelor’s degree.

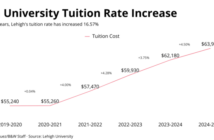

On March 2, Lehigh’s administration announced that the university’s board of trustees had approved a 3 percent tuition increase for the 2015-2016 academic year. The $1,340 increase will boost the annual cost of attending Lehigh as an undergraduate — complete with tuition, room and board and a technology fee — to $58,510, the announcement said.

Four years — indeed, just one year — adds up to quite a pretty penny.

But for some students at Stanford University, which costs about $59,800 to attend annually, those 24 million collective pretty pennies will remain firmly planted in their families’ savings accounts.

On March 27, Stanford announced it will amend its financial aid program beginning next year by offering free tuition to students who come from families making less than $125,000 annually – up from the current $100,000 standard, US News reported. Beyond that, the report indicated that for those students whose family income is below $65,000, the university will foot the bill for room and board, as well. The institution funds, and will continue to fund, its financial aid initiative partly from the tuition revenue that its wealthy students generate, according to US News. Its $21 billion endowment fund certainly doesn’t hurt, either.

For many Lehigh students, access to a financial aid plan like Stanford’s would be a dream come true. But that dream, for now, exists only in the ether.

According to Lehigh’s Office of Financial Aid, 43 percent of the university’s undergraduates receive need-based financial aid, while 10 percent receive merit-based financial aid. The university also pays an estimated $1.5 million in work-study per year. Money generated by tuition, furthermore, is put into a pool and distributed among different aspects of university life, including salaries, wages, general expenses (such as utilities) and financial aid itself.

While the facts seem promising, many students in low- and medium-income brackets still face monstrous obstacles in paying for their college education. The lowest-income students are asked to provide money they may not have in the first place, while middle-income students are often forced to funnel their families’ income directly to their college funds. But why the premium price in the first place?

As Paul F. Campos writes in The New York Times, student enrollment in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs has increased by almost 50 percent since 1995. Although state legislative appropriations for higher education have risen far faster than inflation, total state appropriations per student — because of the increased student population — are lower than they were at their peak in 1990, Campos says. And another major factor driving increasing costs, he says, is the constant expansion of university administration, often to temper campus climate flares or accommodate subjects involving newer technologies.

But the loans that often promise to linger for years after graduation have some wondering whether college is even worth it.

We’re often showered with the sensational success stories of college dropouts like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. But the simple likelihood is that a combination of genius and sheer fortune won’t play so heavily in our favor. For most of us, career-oriented success relies primarily upon a staunch education.

As The Stanford Daily reported, those in the highest levels of government appear to share that belief. President Barack Obama announced an executive memorandum March 10 called the Student Aid Bill of Rights, which intends to “mobilize the energy and focus the attention of everybody…around the basic principles that can make it easier for young people to get the education they need. We can’t allow higher education to become a luxury.”

And yet higher education continues to be a staple of the wealthy and a stretch for the disadvantaged. The cycle of rising education simply continues to perpetuate that disadvantage — to the point that some students who receive scholarships, for instance, don’t report them to Lehigh so the university will not cut the amount of financial aid they will receive.

While Lehigh’s resources cannot automatically guarantee free or cheap education for all students, the university must increasingly contribute to an effort to make education attainable for those of all different walks of life.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.