In a world where numbers and analytics are now much more available than ever before, the game of baseball has seen some significant changes. However, the extent of these changes across different levels of competition varies.

Major League Baseball is often seen as the sports league that is most advanced when it comes to analytics. After all, there is even a word specifically for using advanced statistical analysis in baseball: sabermetrics.

The game of baseball has been dissected significantly in recent years, making information on how to gain an edge on opponents readily available. The statistical part of the game has extended even to college ball, where programs such as Lehigh are using the information that is out there.

“When guys come in and have an understanding of it, the learning curve is so much quicker, and it makes for a more productive career,” said Sean Leary, Lehigh’s baseball coach.

For players, having an analytical mind and being able to process visual information are traits that are valued on the team.

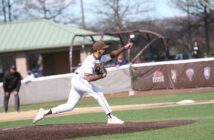

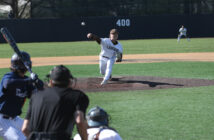

“We always watch video and take a look at guy’s swings,” senior starting pitcher Kevin Long said. “For me as a pitcher, I know where I want to pitch them basically.”

The use of analytics extends to several areas for the Hawks’ program. Leary mentioned pitching to contact and throwing first pitch strikes as important attributes for pitchers, and plate discipline, getting on-base and shrewd base running as crucial for hitters. These are skill sets that can be studied a lot more extensively than before now that there is more information available.

Leary elaborated on the base running, even saying that the team that has been able to take more free bases on the base paths by stealing bases and knowing when to advance winds up winning the game around 90 percent of the time.

“On the offensive side we like guys who make contact and get on base and from the pitching side we like guys who can pound the zone with multiple pitches,” Leary said. “And obviously, when push comes to shove, I’m a defense-first guy so that metric means as much to me as anything.”

Long said that as a pitcher, there are certain benchmarks to appropriately measure performance. Specifically, he sees a pitching approach as being successful if there are at least two strikeouts for every walk, at most 15 pitches per inning and the rate of strikes thrown is at least 65 percent.

Along with this, analytics and the famous defensive shifts go hand-in-hand more than anything. Defensive shifts can include infielders moving to the right or to the left depending on which side of the field the hitter normally pulls the ball toward. They also include the infield moving in to protect itself in situations with a high probability of a bunt.

From this information, the Lehigh baseball team has access to a collection of spray charts, which show detailed information on where hitters tend to hit the ball, so that the infield knows the most effective way to align itself in preparation. This is shared with both the team’s hitters and pitchers.

Limitations at the college level

However, there are some limitations to how the team uses analytics. For a variety of reasons, college programs in general are far behind MLB in how big of a part the analytics play in the game.

In regards to shifts, MLB is known for its rise in cases of three infielders being on one side for extreme pull hitters, especially left-handed power hitters who hit almost strictly to the right side of the field. However, this is much less common in college ball, and is rarely ever seen in a Lehigh game by the Hawks or by the opponent.

“If I over shift and our guys miss the spot all day, we are not helping the over shift,” Leary said. “We are not playing to the data that we put out there. It has been a huge part of what we do, but I would say it’s very much married to an old school approach, too, of just a feel of our own level, a feel of the team and a feel of the opponent.”

Specifically, Leary is hesitant about putting three fielders on one side, a situation he refers to as the over shift, because it can be countered easily at the college level. He fears that at his level, it would backfire as hitters would successfully be able to bunt the ball to the neglected side of the field for an easy opportunity to get on base.

However, there are definitely philosophical differences between coaches at the college level, and that plays a part in which strategies certain programs like to implement. For example, sacrifice bunting — a bunt designed to advance the runners that are already on base, although the batter will probably get forced out at first base — is used a lot in college baseball now. How much teams sacrifice bunt depends on a lot on coaching philosophy.

This applies to defensive shifts as well. Some programs use them more than others. Ben Jedlovec, the president of Baseball Info Solutions and instructor of a course in Sabermetrics at Lehigh (Economics 295), believes shifting is a beneficial strategy for all levels.

“Certain hitters, who might be more higher profile, more prolific hitters, who may have the one-dimensional power approach…why not shift them at the college level if it can help you out,” he said.

He added that across any level, there are players who have the type of skill set that would make shifting a correct strategy.

Balancing old-school and new-school

Jedlovec described another misconception about how strategies are implemented. He believes that one should not have to choose between using mainly numbers and using mainly scouting information, because a successful strategy naturally can incorporate both at the same time. The analytics can confirm that what is seen when scouting is reliable and vice versa.

“Analytics and numbers should be factored into every decision in some extent but by no means are you making any decision based on numbers,” Jedlovec said. “Every decision should be based on numbers and every decision should be based on your intuition and scouting at the same time.”

Leary agrees with using both strategies, saying that how much he emphasizes each is probably close to 50-50. He takes advantage of the technology that is available and shares it with his players. However, he also makes several decisions based off of a gut feeling, mentioning how he commonly does this when deciding whether or not to pull the starting pitcher from the game in crucial sixth inning or seventh inning at-bats.

Still, he is fortunate to be able to work with this data.

“From 15 years ago to today, there’s so much more technology available that we want to use as much as possible,” Leary said.

While the interaction between baseball and analytics has definitely changed a lot over the years, it remains a fluid situation today. Even more technology is expected to be available going forward.

Because of this, programs every year have to reevaluate which analytical approaches are used and how they are used. Leary said that based on what additional technology becomes available, more can be utilized as a way to gain as much of an edge on the opponent as possible.

Still, baseball is a game of both old-school and new-school philosophies, and to most, both have a sacred place in America’s pastime.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.