This year’s presidential election season has been underfoot for months, with more than half of U.S. states and territories voting or caucusing to select their party representatives.

On April 26, Pennsylvania voters will flock to their polling places, contributing to an already high primary election voter turnout. According to the Pew Research Center, 2016 primary voting has reached its highest percentages for both Republican and Democratic voters since the ’80s and ’90s, respectively — disregarding 2008’s record turnout. But this year’s numbers rival even that election season, according to the data.

But while the current national race may see steadily increasing participant numbers, the same cannot be said of elections that take place closer to home.

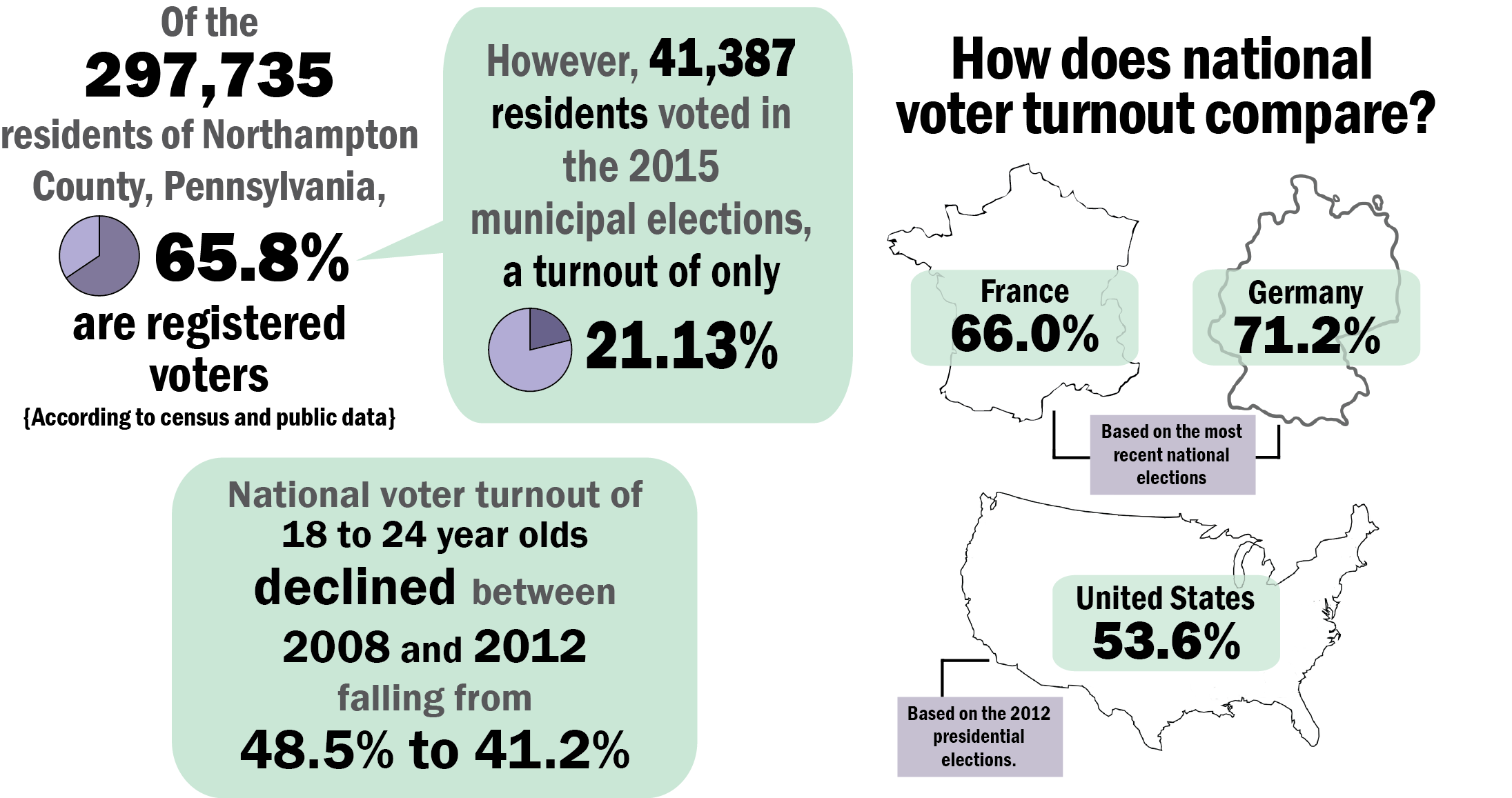

Of the 297,735 residents of Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 65.8 percent are registered voters, according to census and public data.

Kelly McCoy/B&W Photo

On Nov. 3, those eligible were given the opportunity to cast their ballots in municipal elections, part of a greater collection of United States general elections taking place on the day.

The 149 county polling places stayed open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. for decisions to be made on candidates, among which were prospective selections for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court as well as district attorneys and mayors, among others.

Yet only 41,387 Northampton residents took part, resulting in a 2015 local election turnout of 21.13 percent.

But these low numbers are neither unique to the county nor rooted in any one issue. Mirroring the national trend, local election turnout has been consistently low — Northampton county’s data from November proving no different. Officials and voters alike share a two-fold reasoning for dwindling civic participation: a lack of political engagement supplemented by structural barriers.

“It’s a rational behavior, sadly, for Americans to only vote in presidential elections,” said Saladin Ambar, a professor of political science at Lehigh. “And even then, it’s harder for voters to see the efficacy of their vote.”

While gauging importance of a single vote in an election of millions might pose difficulties on a national scale, local elections face a similar, yet heightened, issue. Local elections may more directly impact voters based on sheer government-citizen proximity, but according to Ambar, those same individuals may find it hard to perceive a county judge or school board member’s position as clearly as a president’s.

Like low voter turnout, this conceptual challenge exists beyond Northampton’s borders.

Heather Simoneau is a Lehigh County resident living in Upper Saucon Township and consistently votes in local elections. She said she understands how ambiguity surrounding positions and jurisdictions can translate into voter apathy regarding local government.

“They might not know what a position might do,” she said. “Upper Saucon has a board of supervisors, is that like a mayor? What do they do? What are they deciding? . . . What does it matter then, what these people are doing?”

For J. William Reynolds, a Bethlehem city councilman who won re-election last November, as far as understanding respective local positions goes, “people tend to lump everyone in government together.”

Low turnout is not entirely a fault of misconceptions regarding the positions, but rather, the issues that these politicians address.

Reynolds acknowledges that there’s a contrast between national issues and localized ones. While a presidential election might consider the issues of marriage equality or foreign policy, local politics deal with public safety or road maintenance, he said. Reynolds believes this comparison accounts for some disinterest.

“The services that are provided by your local government won’t often be the type of things that people get as fired up about,” he said.

This lack of passion might befall any group of voters, but of an already-low turnout percentage, youth voters — generally considered between 18 to 24-year-olds — are a group of even less engaged individuals. According to a Pew Research Center study based on a census voting report, young voter turnout declined between 2008 and 2012, falling from 48.5 percent to 41.2 percent.

But this discrepancy of interest among the youngest voters is prevalent locally, too. That much is apparent in Jeffrey Corpora’s Easton Area High School classroom, where he teaches advanced placement government and politics.

“Some of them are engaged,” Corpora said. “(But for) some of them, politics is like a foreign language to them and there’s no interest.”

Corpora attributes some of his students’ disinterest to the pertinence of some issues to young adults, as opposed to their parents.

“There’s that disconnect,” he said. “Someone else is paying the bills.”

So while topics such as social security might not garner the needed interest for a young, prospective voter, Corpora believes making the connection relies on making the topic matter to the individual. Student loans and debt, he said, are something that, given the socioeconomic context of Northampton County, will be a topic many students become familiar with.

“That’s something that’s right in front of us now,” he said, referring to his class of high school seniors. “So that might be the issue that’s going to drive those voters.”

But even equipped with this political drive, voters may meet logistical obstacles as they head to the polls. While the difficulty of garnering political interest and participation plays a large role in low voter turnout, the physical challenges of casting a ballot also have influence.

“We had election day on a Tuesday,” Reynolds said. “Oftentimes, if you’re working, you might not have time to get to the polls.”

Though polling lasts for 11 hours on the day, this may not be sufficient.

Simoneau, who works for Lehigh University as an exempt employee, said she’s privileged with flexible hours. But for working-class families without 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedules, heading to the polls may not be as simple as balloting during a lunch break.

“Four polling places (in Upper Saucon Township),” she said of her own region. “Then you look at the lines in Allentown or even in Bethlehem — these long lines for people to vote.”

Faced with structural inconveniences, a federal holiday or weekend might be solutions to providing the necessary access to boost votes.

Other countries have adopted such practices, such as France and Germany, nations with voter turnouts of 71.2 percent and 66.0 percent, respectively, in the most recent national elections, according to Pew Research Center data. Comparatively, the 2012 U.S. presidential election turnout was 53.6 percent, the data reads.

“We could make it easier,” Ambar said. “Election day could be a federal holiday . . . Other countries don’t have this problem.”

Reynolds said alternative measures exist, such as same-day voter registration, early voting and online registration — methods that “more progressive states” have implemented.

In 33 U.S. states, not including Pennsylvania, early voting is permitted, according to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures. While all states permit absentee voting, 20 require an excuse, the data reads. Pennsylvania is one of them.

And while the existence of these regulations may be limiting, awareness and comprehension of voting and election logistics may be problematic, too.

For Lehigh student and Bethlehem resident Faarah Ameerally, ’18, it’s pre-election logistics that have barred participation. She has yet to vote in a local election.

“(Local politics) wasn’t something that was brought to my attention,” she said. “When the elections are held, where they’re held, how to get there (and) how to register isn’t something that is very well known.”

As a student, she said, there’s little time to learn the issues and the subject matter is “extremely difficult to follow along with.” Only after studying political science did Ameerally feel informed enough to participate.

But according to Reynolds, it’s fault that cannot be placed solely on government, nor citizen.

“As a country, and a state, we need to make it easier to vote,” he said. “At the same time, I . . . think that Americans don’t often pay as close attention to their government for issues that they should.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.