Bethlehem city government launched an initiative known as “We Build Bethlehem” in an effort to increasingly seek out public opinions for citywide decisions.

It was imagined and created by Mayor J. William Reynolds, who was elected five months prior to the program’s inception in April 2022. It became part of a greater effort to bridge communication gaps between constituents within Bethlehem and the leaders tasked with addressing their problems.

They planned to do this for a community that is culturally, economically and geographically diverse — yet divided.

Janine Santoro, Bethlehem’s first director of equity and inclusion, said the mayor’s staff came into office with a focus on proactive rather than reactive work.

“When you’re in crisis mode, you’re just trying to do the next thing that is going to soften the blow for whatever is coming right now,” Santoro said. “Instead, we are trying to find ways to create systematic support for initiatives that anticipate and serve communal needs to prevent crises.”

She said the mayor’s office has a “refreshing” way of working. They are not hesitant to alter plans — something she believes some organizations, especially in the public sector, shy away from.

As one example, when they realized the online portal for the We Build Bethlehem Initiative was geared more toward English-speaking middle- to upper-class individuals, they pivoted. The office started distributing paper surveys in English and Spanish and offered pop-up community engagement opportunities.

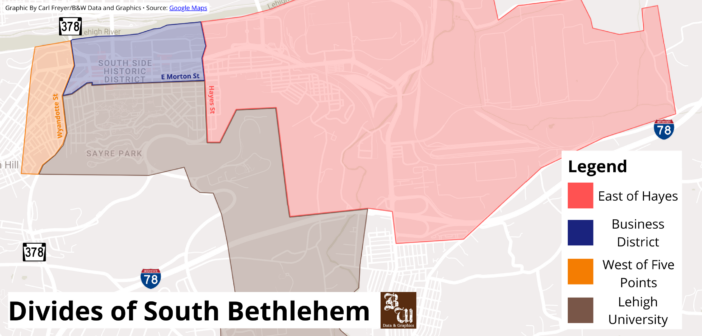

Yet, understanding and tackling these projects is challenged by geographical divides, especially within the South Side.

Bethlehem first united three geographical jurisdictions in 1741, then known as West Bethlehem, South Bethlehem and Bethlehem.

Now, however, the most commonly known division exists between the North Side and the South Side.

Cars line up along New Street on the South Side at a red light, making their way toward Lehigh’s campus. This spot is close to one of the unofficial geographic divides on the South Side between the Lehigh University area and the business district on Third and Fourth Streets. (Sam-Barney-Gibbs/ B&W Staff)

Political science professor Karen Pooley teaches courses on city planning, neighborhoods and housing issues at Lehigh. She said the decision to allow a casino to be built jumpstarted South Bethlehem development about a decade ago. Funds were channeled back into the South Side community, invigorating predated community action groups and organizations.

“Now, we have two areas,” Pooley said. “So the challenge is: does one sort of take all the oxygen out of the room? How do you make sure that both of those parts of town continue to benefit from that kind of focus and support?”

She said the Northside Alive initiative was created to replicate what is now known as Southside’s Tomorrow. Both initiatives assemble community partners, residents and small businesses to invest in the livelihood of constituents.

But, she said, these voices tend to consist of the bigger organizations in the area, keeping them focused on big-picture ideas rather than noticeable changes.

Before it was called Southside’s Tomorrow, the initiative went through various iterations. The name changed yearly to reflect progress over time: Southside Vision “2010,” “2014,” “2020,” until “Tomorrow” eventually stuck.

Councilwoman Rachel Leon — the only representative of Bethlehem City Council residing on the South Side — is concerned about what “tomorrow” will resemble for residents of South Bethlehem.

Leon said these initiatives don’t necessarily solve many of the preexisting struggles the rest of the community faces.

“It feels like a different city at this point,” Leon said. “If we’re going to be keeping promises to the South Side, we need to look south of Fifth Street, east of Hayes Street and the Five Points area. That’s all South Side too.”

People cross the street on East Fourth Street near the Five Points intersection. This spot is close to one of the unofficial geographic divides on the South Side between the Lehigh University/business district areas and more local residents to the east. (Sam Barney-Gibbs/B&W Staff)

Not only may the North and South sides be competing for attention, but the priorities within each district of the South Side also skew.

Pooley said the development boom is becoming a pattern on South Side streets — but the construction on East Third Street resembles a different Bethlehem than east of Hayes Street, west of the Five Point intersection or around Lehigh University.

“It’s not one neighborhood,” Pooley said. “You can think you’ve solved something, but it really is only going to impact these four blocks. What happens in one may influence what happens in another — it may be totally unfelt in another.”

The pattern of planning to augment Bethlehem is something Leon thinks can actually take away from the wants and needs of what — and more importantly who — already exist there.

With geographic divides instigating conflicting discussions both within South Bethlehem and between the North and South sides, Leon understands how difficult it is for local government to gauge community needs.

Regardless, she said she thinks some more basic but significant problems must be acknowledged and addressed head on.

“Talk to the people who live there — not just the nonprofits or the for-profits,” Leon said. “It would behoove us to spend the time to make real connections within the community where they are comfortable to tell us their stories.”

A church at the intersection of Hayes Street and Fifth Street. This spot roughly marks one of the unofficial geographic divides on the South Side between the Lehigh University/business district areas and more local residents to the west. (Sam Barney-Gibbs/B&W Staff)

Santoro said the city government doesn’t address citywide issues “in a vacuum.” They facilitate roundtable conversations with community stakeholders and residents so they do not assume what is best for Bethlehem.

“The city can give power and ease to our community leaders — that’s the way we would like to structure, and that’s how Southside’s Tomorrow has been operating,” Santoro said.

Pooley said she thinks there is potential for the city to reinvest in existing infrastructure. Abandoned storefronts, historic structures and “fancy” new buildings could become part of the commercial “corridors” where people interact and fulfill daily needs.

She said it takes a concerted effort for a city to admit high-end facilities are not the only form of productive development. Rather, variety is a key step in fulfilling the stratified needs of South Bethlehem citizens.

More people getting what they need from similar spaces means more foot traffic and better business.

“When you have a place that’s eclectic, there’s room for a whole bunch of different kinds of stuff that could attract a whole bunch of different kinds of people,” Pooley said.

But, she said there has been less focus on these basic, hyperlocal needs. She thinks more attention and investment has been given to attract suburbanites and students, meaning the people interacting in South Bethlehem are mostly traveling into the common spaces rather than already living in them.

Leon said Reynolds’ administration has taken notable steps forward in policy areas she thinks are important for South Bethlehem. Though they may not agree on how policies are handled, she said she believes much of the foundational content and intention behind their work is aligned.

“I think there is a genuine desire from this current administration to understand what’s going on on (the) South Side and how certain people feel on (the) South Side,” Leon said. “A united community is much more able to advocate for itself.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

1 Comment

Wow, what an amazing insightful, well researched article. Bringing to light something that has been felt in the wide Southside community, but not necessarily talked about with such clarity and plan of action.