Inspired by the popular children’s song “Watermelon Meow Meow” by artist Innovation Movers, a public health project of the same name is providing College of Health students with a real-world example of how quickly an epidemic can spread.

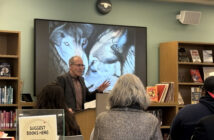

Tom McAndrew, a professor of community and population health, executed the project by creating a fake epidemic simulation for students in his Outbreak Science & Public Health Forecasting class this semester. The project extends beyond the classroom to the general student body to mimic the spread of an epidemic.

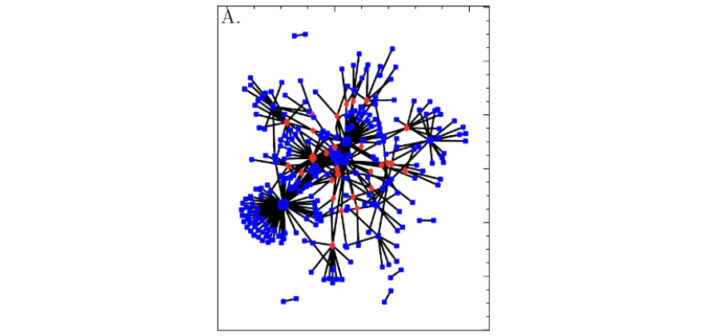

Infectees and infectors use a website to log infections, which can then be used by students in the class to analyze their own outbreak data.

When presenting Watermelon Meow Meow to the class — which he worked to develop over the summer — McAndrew incentivized students with extra credit to participate.

He was “patient zero” and infected the class by showing them the Watermelon Meow Meow video. Each student was then responsible for infecting at least three people.

“The course is called outbreak science,” McAndrews said. “So (students) should have their own outbreak, right?”

Neha Paras, ‘25, a population health major, developed a website over the summer to track the project.

Paras said there are three important features on the website — the Watermelon Meow Meow video itself, fields to collect the Lehigh emails of the infector and the infectee, and a contact network to show viewers the number of people involved in the project.

McAndrew said the project will teach students about contact networks and mathematical models of infectious diseases. It also reveals social dynamics, such as trust networks and major infectors.

One of the infectors, Ava DeLauro, ‘26, said the simulation helped her better understand how diseases can spread and die out.

“It mimics how a disease works in real life,” DeLauro said. “It kind of just dies down when people become less infected.”

McAndrew said he expects the project to reveal groups on campus that have a significant impact on infectious disease dynamics. He said the data will make this observation clear, since he expects students to infect others who are in and closer to their social circle.

“Typically in epidemic models, you say ‘Well, everybody’s randomly bouncing around infecting one another in some large space,’ which is dumb,” McAndrew said. “I know that you don’t do that, and I don’t do that either,”

Many professors were interested in the results of the Watermelon Meow Meow experiment and have been following along since the start. McAndrew said even the Dean of the College of Health, Elizabeth Dolan, was infected by DeLauro.

Rochelle Frounfelker, a professor of community and population health, said she’s focusing on the educational side of the mock epidemic.

Frounfelker said McAndrew asked her to evaluate the simulation’s impact on student learning, and she believes the project will positively impact student engagement.

“I thought this is a really cool way to integrate experiential learning within a classroom that’s focused on data science and biostatistics,” Frounfelker said.

McAndrew said he believes students will learn to analyze the data from the epidemic’s contact network to help them to understand data sets.

“I think what it’ll teach students is, what can you do with this data set?” McAndrew said. “How can you incorporate it into mathematical models of infectious diseases?”

Hsuan-Wei Lee, an assistant professor and public health researcher, said he joined the mock epidemic because it aligned with his research interests in information propagation and diffusion.

Lee wanted to understand why people share information and what triggers them to share within specific groups. He also said the simulation has been successful so far.

“I love to see how networks grow from nothing to some phenomena,” Lee said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.