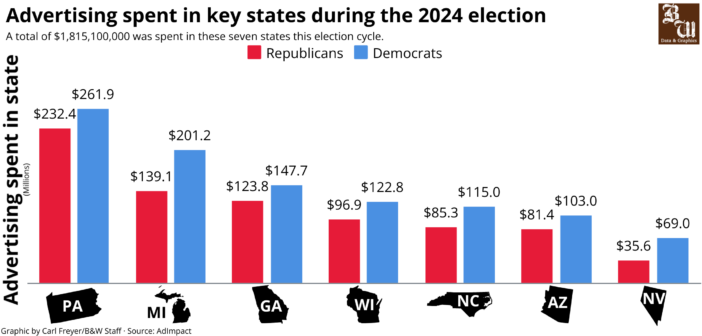

Pennsylvania was widely considered the most decisive state in the 2024 presidential election, and advertising played a role in constituents’ opinions and voter registration.

Sitting in the middle of political races — from the local state house to the presidential race — is not unusual for the Lehigh Valley.

“You happen to be at the very center of this election cycle,” Christopher Borick, a professor and the director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion, said. “So the number of ads that are being run is higher than many places in the country.”

The Keystone State had the most presidential advertisement reservations in the nation, totaling $137 million, according to The Conversation.

Marie Schenk, an assistant professor of political science at Lehigh, said she’s lived in Pennsylvania for a few years and has been “stunned” by what it means to live in a swing state.

She said despite studying politics for years and often hearing about the overwhelming flood of advertisements leading up to the election, she’d never experienced it as intensely as she did during this cycle.

“I (was) getting daily postcards from people urging me to vote,” Schenk said.

He said campaigns study audience demographics and viewing preferences to create targeted content.

Although television networks offer some level of demographic targeting, social media enables “micro-targeting in a much more direct way,” Borick said.

Ava Lorette, ’26, said she noticed the targeting of these campaign advertisements.

“Social media ads are more so geared towards a younger audience where television ads are more geared towards older audiences as they are the ones who are still watching cable,” Lorette said.

Brian Fife, a professor and the chair of the political science department at Lehigh, said he’s seen significant changes in political advertising strategies over his career.

“Throughout my lifetime, there has been a tendency for political candidates to use negative advertising,” Fife said.

Despite public complaints about negative political advertising, Schenk said emotional and negative ads remain effective campaign tools.

“People really complain about negative, scary and toxic advertising, but the fact of the matter is, it works,” Schenk said. “It gets people’s attention, and it gets people’s emotions running high.”

It’s common for voters to complain about the negative valence of campaigns, Schenk said, but campaigns continue to rely on them because they prove to be effective at motivating voters.

Borick said campaign advertisements often depict opponents in black and white, while presenting the incumbent, who the advertisement is in favor of in color — potentially swaying voters’ perceptions.

“It’s all based on emotion,” he said.

Schenk said older voters are typically viewed as more reliable targets for political campaigns since they have established voting histories, unlike first-time voters like college students, whose turnout can be less predictable.

Campaigns approach college students with particular caution, he said. While students represent potential new voters, they’re seen as a risky demographic to target.

“College students are always interesting because it’s not necessarily clear where they’re going to be voting,” Schenk said. “They’re eligible to register to vote at their college campus, but they’re also eligible to vote at their permanent home address and vote absentee.”

Borick said students encountering local political ads should ask questions and think about what’s not being shared.

“The very first thing I always ask is ‘what is missing?'” Borick said. “‘What is included in the frame?’ ‘What is outside the frame?’”

He said advertisements might use factually correct statements reported in media but remove surrounding details that give viewers a complete picture.

Fife said the complexity of modern political messaging requires careful analysis from voters.

“The politics of deception is omnipresent, and context matters,” Fife said.

For local voters trying to navigate the barrage of political advertising, Schenk said voters should maintain a skeptical approach and check multiple sources for corroboration.

“Look at research-backed sources as it will give you a clearer perspective,” Schenk said.

However, Borick said research hasn’t shown a clear connection between political advertisements and voter behavior. Even when conducting it from a social science perspective like experiments or polls, it’s challenging to measure impact since people don’t always remember which ads they’ve seen.

In today’s hyper-partisan environment, Borick said campaigns recognize their ads won’t dramatically shift voter preferences.

“It’s really hard to move a lot of voters,” Borick said. “Campaigns think on the margin — ‘Who can we get to turn out that might not turn out?’”

He said despite these uncertainties, especially in the 2024, campaigns continued investing in advertising because they’re not going to risk not trying given the close margins.

He said since they had the financial means to do so and knew how close the race was at the presidential level, advertisers tried to reach as many voters as possible.

In the future, as the political landscape and means for disseminating information continue to evolve, advertising will likely remain a key part of election campaigns.

Fife said citizens should continue to do their homework to fact-check what they see in advertisements.

“If candidates and their aides knew that we, the people, had a more sophisticated knowledge of public affairs and policy, they would be forced to make more substantive and fact based ads,” Fife said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.