Eating disorders, masquerading through college campuses under the guise of a quick diet or fitness kick, often remain unrecognized or overlooked until the consequences are no longer ignorable.

Lehigh senior Taylor Wise said she didn’t believe she had a problem because she felt as though she was in command of her actions.

“I always thought I had the control, but then I realized it had control of me,” she said.

Another Lehigh senior student athlete, who asked to remain anonymous, said he did not even see the issue himself at first.

“I actually didn’t realize it was a problem until my mom brought it up,” he said.

These alarming sentiments reflect an increasingly common mentality among both male and female Lehigh students facing pressure everyday to perform flawlessly in school, social and, for some, varsity athletics settings.

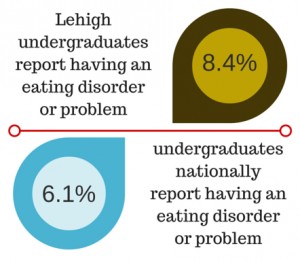

According to the Lehigh Office of Health Advancement & Prevention Strategies, data from the Spring 2014 National College Health Assessment revealed that 8.4 percent of Lehigh undergraduates report having an eating disorder or problem, compared to 6.1 percent of undergraduates nationally.

When broken down further, 1.7 percent of Lehigh undergraduates reported that an eating disorder negatively impacted their academic performance compared to the 1.3 percent of undergraduates nationally. Additionally, 1.4 percent of Lehigh students said that they were diagnosed or treated for anorexia and another 1.4 percent for bulimia. Both of these numbers were higher than the national average, which sits at 1.2 percent and 1.1 percent, respectively.

According to the 2013 National Eating Disorders Association report, Eating Disorders on the College Campus, the most common time for an eating disorder to onset is between the ages of 18 and 21.

The correlation is more than coincidence.

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, 91 percent of college women attempt to control their weight by dieting. Dieting, although commonly perceived as a stride toward a healthier lifestyle, can have adverse effects.

“That part has become really normal in American culture,” said Rita Jones, the director of the Women’s Center at Lehigh. “Everything is focused on weight issues or weight loss because of obesity.”

The most common clinical types of eating disorders are bulimia, anorexia and binge eating disorder. Less common disorders include body dysmorphic disorder, orthorexia, bigorexia, night eating disorder and feeding disorders not elsewhere specified.

Psychology professor Tim Lomauro said despite these categories, eating disorders often operate on more of a continuum than a distinctive diagnosis.

Disordered eating, often characterized by an obsession with food, diet or body image, is also extremely prevalent on college campuses. However, since clinical criteria are not met these victims are often not fully addressed.

“If I just go in with a standard approach, I’m going to miss almost everyone I’m targeting,” Jones said. “It can’t be a one size fits all approach.”

Lehigh staff psychologist Cristina Cunningham and counseling psychology doctoral candidate Maxine London agreed with Lomauro, saying that various factors affect students differently so there must be different ways to help different people.

“The hardest thing can be to figure out the starting point, what this individual needs,” Cunningham said.

Finding that starting point is difficult not only for staff trying to help, but also for students themselves.

Wise, a senior pre-med student, current Zeta Tau Alpha sorority member and former Lehigh varsity swimmer, said she has always faced a lot of pressure. She said the diet change first began in middle school, but as her swimming career picked up and pressure from coaches increased the problem turned into a habit.

Wise was a sprinter and coaches were not shy about telling swimmers they needed to stay light and thin, yet extremely strong if they wanted to be successful in the pool.

Upon entering college her diet morphed into an obsession, and she said she became extremely hyper-aware of not only her habits but those of her teammates, as well.

“I knew I had an issue with eating, but I didn’t know I had an eating disorder,” Wise said.

During her sophomore and junior years the problem intensified and she said she started to become anemic from purging. A pre-existing heart condition that she had began to worsen at an alarming rate. Finally, during a routine check-up a doctor noticed how severely imbalanced her heart, circulation and other vital signs had become and that was the end of her swimming career.

For her, that news was devastating.

“I wasn’t done,” she said. “I still had work I wanted to do.”

Another senior Lehigh student athlete told a similar tale with one seemingly important difference. He is male.

“They’re slipping by when in fact what they’re doing is not healthy,” Jones said when speaking about the tendency to exclude male undergraduates from certain body image efforts.

Male students feel the sting of that stigma, especially when they find out counseling and talk therapy are part of their treatment.

“You’re a guy, you don’t do that,” said the senior student athlete.

Cunningham and London said they see both male and female students in the counseling center despite the stigma of eating disorders as a strictly female problem.

The male student said it started out as a quick method to slim down for athletics and to look better, but it soon surpassed the point of a minor diet.

“It got to the point where it was like clockwork after every meal,” he said. “It was like going through a week of hard practices without eating.”

One of the most dangerous parts of eating disorders is the permanent, lingering effects. In some of the most severe cases victims have their colon or half of their intestines removed or go onto dialysis just to stay alive.

Despite the very real consequences of an eating disorder, recovery to a functional state is possible and does not have to be an independent journey. Along with nutritional conscientiousness, counseling and support play a key role in recovery, according to both students and experts.

The Lehigh Health and Wellness Center nurses and doctors are aware of the prevalence of eating disorders on campus and try to offer nutritional advice while working closely with counselors to get students help.

The counseling center homes trained professionals who offer both individual and group counseling to students. Students agreed that advertising both group and individual counseling services more openly and obviously would be extremely valuable.

Wise said the group counseling sessions were the most helpful to her because she was able to relate to peers who understood her struggles. The group meets once per week and consists of roughly 10 students who often attend in conjunction with their one-on-one sessions.

The Women’s Center has also spearheaded numerous efforts to help Lehigh students open dialogue about eating and body image issues. During the last week of February the center headed up an agenda of events in support of National Eating Disorder Awareness Week.

From an academic perspective, Lomauro teaches a psychology class focused on eating disorders and body image that originated from student demand, yet some resources seem to be hidden in the woodworks, much like the students suffering.

The consensus among Jones, Lomauro, Cunningham, London and the students interviewed was that support has begun to sprout from many different departments on campus, but there is still work to be done.

Students say that many resources in existence are not fully reaching the student population and therefore not making a maximum impact. For example, Women’s Center and Student Affairs offer two separate webpages on eating disorders. Jones said all sources would be most useful if they were connected. They will be working to provide a link to the Student Affairs page from the Women’s Center page.

Jones also suggested engaging coaches and other faculty members in awareness training could make a positive impact on the recognition and recovery of struggling students.

“The more I go through recovery, the more I can see the bad part of me going away and the good moving in,” Wise said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.