On top of studying for 4 o’clocks and balancing his extracurriculars, Kaung Myat, ’19, has a crisis on his mind.

More than 8,000 miles across the globe, his home country of Myanmar, also referred to as Burma, is in the middle of a humanitarian crisis.

Myat was born in Yangon, a city of around five million people in southern Myanmar. He attended an international school his entire life until he came to the United States for the first time at the start of Lehigh’s freshmen orientation.

Myat’s father, who worked in the fishing industry, was able to create a comfortable lifestyle for the family by the time Myat was born in 1997.

However, Myat’s family’s status is much different from that of his Burmese friends. Many of them have grandparents who work in the government and have access to a large amount of power and resources.

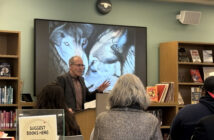

Courtesy of Kaung Myat

In Myanmar, 25 percent of the parliament is run by the military. When Myat left for Lehigh in 2015, there were parliamentary elections and power transfers as political instability started to hurt the country’s economy. Myanmar as a whole had become untrustworthy in the eyes of other nations.

Myat said since he’s been at Lehigh, things have gotten worse for Myanmar.

“It was so quiet during my time there, and then something sparked and everything became undone,” Myat said.

In August, clashes broke out after a Rohingya militant group claimed responsibility for attacks on Myanmar’s police and army posts. The government declared the militant group a terrorist organization and launched a campaign to expel the Rohingya people, a Muslim minority in western Myanmar. Myanmar is a predominantly Buddhist country.

Since August, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced and forced to flee to neighboring countries. The Myanmar government has been condemned by the global community and the United Nations. According to the Council of Foreign Relations, human rights groups and United Nations leaders have described the events as “ethnic cleansing.”

“It’s in our culture that part of being Buddhist is you leave things for other people, show compassion and show that you care,” Myat said. “And you never cause harm to other people. Based on what the media is saying, I think it’s messed up to hear how another Buddhist could do atrocities like these.”

Myat said the crisis is sending the entire country into a downward spiral, especially when international condemnations and sanctions are enforced.

“I don’t know who started this, who’s playing what role, because it could be politics (or) something bigger,” Myat said. “It’s just so inhumane. You don’t see the purpose of why people are doing this. I feel bad that this is happening, that people are suffering.”

While Myat condemns the actions the government is taking to displace the Rohingya minority, he is hesitant to point fingers at a specific group for causing the crisis.

He believes media coverage that places blame on all sides might leave people with a blurry picture of the crisis.

“Burmese media is providing support, but world media is pointing blame at the government,” Myat said. “There are so many things you don’t know, that if you kept thinking about it, it would be a waste of time. I’ll just be waiting until more information comes out.”

Despite the situation unfolding in his home country, Myat tries to stay dedicated to his studies and work at Lehigh. He has only spoken to two other people about the issue, both of whom are professors.

As vice president of the Global Union, Myat is less inclined to talk about the issue, especially at Global Union, because he wants people to first understand Myanmar’s culture before he launches into a disturbing and complicated account of his country’s current state.

Clara Buie, the program director of Global Union and community engagement, said it is out of place for Global Union to become fully engrossed in the crisis.

“We really don’t want to take any political stance on issues like these,” Buie said. “Most of what we provide are educational pieces.”

Cheryl Matherly, the vice president and vice provost for international affairs at Lehigh, said it is an extremely complicated issue to discuss.

Matherly, who is traveling in Africa, wrote in an email that organizations like the Global Union and United Nations programs are good ways to engage in campus discussions regarding human rights and refugee issues or the complexities of diplomatic responses to a humanitarian crisis.

“The crisis of the Rohingya in Myanmar is of tragic proportions, and the international community has still not issued an effective response,” Matherly wrote. “Even those aware of the refugee crisis may well not understand its roots, impact on southeast Asia or reasons for lack of response by Aung San Suu Kyi (the State Counsellor of Myanmar).”

For now, the crisis continues to unfold, and Myat continues to wrestle with his distance from home and lack of control.

“What can I do from here? I can’t let go of my education and go home,” Myat said. “It’s horrible that people are dying. More people die everyday. But thinking about it, taking a side, who could I even tell it to?”

Despite all that is happening in his home country, Myat hopes the crisis can be resolved in a timely manner.

“I hope people come up with a solution for this issue,” Myat said. “And any solution is worth considering in a time like this.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

1 Comment

If the Muslim group claimed responsibility for the attacks why does everyone have such a hard time wondering why the government has taken retaliatory action against them?