Jeanne Clery was raped and murdered in Stoughton Hall in 1986.

Jeanne Clery was raped and murdered in Stoughton Hall in 1986.

More than 30 years after the tragedy, Clery’s name echos in colleges and universities across the country in the form of the Clery Act, which requires institutions to report crime statistics, notify campus communities of threats and create and distribute annual campus security reports.

On Oct. 4, President John Simon, Provost Patrick Farrell and Vice President of Finance and Administration Patricia Johnson sent an email to notify the campus community that Lehigh Title IX Coordinator Karen Salvemini had received eight reports of sexual misconduct since the start of the 2018-2019 academic year.

“(The increase in reporting) revealed to me some of the lack of understanding of some of the really basics in what happens after reporting, what does get reported (and) how different Clery reporting and those numbers are from the number of cases that come in,” Simon said.

Investigation

Brooke DeSipio, the director of Gender Violence Education & Support, said more students are likely to choose to go through the university process, which involves a civil process, than the criminal process that appears in Clery reports.

Criminal cases require the victim to report to the police, have a district attorney accept the case and have the case go to trial, which DeSipio said rarely happens.

Aside from the Clery report, data on reports of sexual misconduct can be found in Equal Opportunity Compliance Coordinator Annual Report that Salvemini compiles.

“I’m not required to do my report,” she said. “I did it because I thought it was important for our community to have an idea of what I am doing and what comes to my office.”

DeSipio said the university uses preponderance of evidence — a “more likely than not” standard — and the most the university can do is expel or suspend someone.

Cases of sexual misconduct at the university level are investigated by two co-investigators. Salvemini is always an investigator, and her co-investigator is determined based on who is accused of the behavior.

“I basically make sure that we move forward and follow the process,” Salvemini said. “That we interview people, document everything, put a report together.”

Investigations are supposed to take 60 days under university policy, but Salvemini said they sometimes take longer if there are several investigations going on, or if she is occupied with her regular education workshops.

Salvemini said she wants to get the right answer, not the quick answer.

DeSipio said the investigators put together a report that is then presented to a panel.

The victim is not questioned or in the room with the perpetrator at any time during the investigation process, and students are not included on panels to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of survivors and alleged perpetrators, DeSipio said.

Salvemini is also responsible for making sure parties have the resources and support measures they need, such as academic support or a change in residence hall placement.

“Because in a gender violence incident, the survivor’s control is taken from them and they don’t have choices, it’s so important in the aftermath to give as much choice and control back to the person,” DeSipio said.

DeSipio said the university tries to let the survivor choose the route they would like to take when it comes to reporting, as some people decide not to move forward with the process at all.

Cases where the campus is at risk, however, are cases where DeSipio said the process moves forward regardless.

“We have an obligation to keep this a safe campus,” she said. “So, if we have a situation that puts other members of the campus community at risk the university would need to move forward with that.”

National trends

DeSipio said she thinks sexual misconduct behaviors have been occurring consistently, but it is the reporting that seems to be increasing, due to university policy and national trends.

She said national conversations around sexual misconduct also impact reporting and campus climate.

“Over the last several years from the Cosby case to the Brock Turner case, the MeToo (movement) and, most recently the Kavanaugh (case), there have been numerous national platforms that are encouraging folks to come forward and share their stories,” DeSipio said. “So nationally we are seeing increases in reporting.”

She said national sexual misconduct reporting hotlines saw a major increase in reports after the Kavanaugh hearings.

Salvemini said her office has not seen any significant rise in reporting because of the Kavanaugh hearings or the Me Too movement, however. She thinks sexual misconduct is under-reported on campus, but reporting numbers are more accurate now than when she came to Lehigh in 2015.

“If you look at the annual reports for the two years that are published, the numbers have gone up significantly,” she said. “And that’s a good thing because we knew it was happening but nobody was reporting it before that.”

Salvemini said eventually the hope is that reporting numbers will peak and then decrease, with the help of the prevention work and actions taken to address sexual misconduct on campus.

Conversations about how to make Lehigh a safe and healthy community happen, DeSipio said, because the university wants affected students to come forward and get help.

She said she doesn’t think these issues are pushed under the rug at Lehigh.

“I guess I personally don’t see any reason not to report what’s going on on campus,” Simon said. “Putting the information out there gives people pause and they start thinking about the implications of the information.”

The impact of alcohol

Chris Mulvihill, an associate dean of students, said campus drinking culture can play a role in sexual misconduct cases.

“Alcohol definitely plays a role in a lot of the (sexual misconduct cases) because college students aren’t great at communicating about sex, and sometimes they use alcohol to get over some of that,” he said. “But that doesn’t excuse any of the behavior.”

Alcohol can serve as a date rape drug, Mulvihill said, because the person accused of sexual misconduct may supply the victim with alcohol until the victim is not able to consent.

He said victims can also be too intoxicated to consent even if alcohol is not used in a predatory nature. He said the standard of proof in sexual misconduct cases is “incapacitated” — someone incapacitated by drugs or alcohol is not able to give consent, according to the code of conduct.

Incapacitation comes on a spectrum.

People can be incapacitated, for instance, he said, if they are unconscious, unable to grasp where they are or what’s around them, incapable of using motor skills on their own or lose bodily function. In addition, there are cases where it is harder to tell if the victim is incapacitated because some people can seem perfectly fine when they’re blacked out.

Victims may not label experiences as sexual assault, Salvemini said, perhaps because they think they were at fault because they drank. She said self-blame impacts some people’s decisions not to report sexual misconduct.

Resources

President John Simon thinks the discussions around sexual misconduct on campus will continue to increase.

“Having campus dialogue surrounding (sexual misconduct) is a really good thing,” he said. “The question is how do you do that, and how do you engage? You can get those who are already engaged in a dialogue, but how do you have dialogue on a campus that engages those who need to be engaged?”

For the past three years, Salvemini said her office has offered annual harassment training to students. This year, the mandatory online training was tailored to specifically address sexual harassment and misconduct. These training programs are administered in addition to on-going in-person training sessions held throughout the year.

She said the goal of the training is to make sure that people have a basic understanding and are thinking about these topics and behaviors.

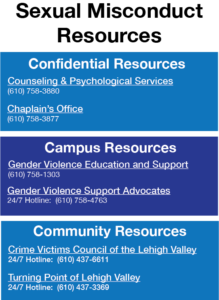

In addition to educational measures, there are resources and support services available to students.

“I want our students to very clearly hear this message: there is someone here who believes in them and will support them,” DeSipio said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

1 Comment

Seems like movement in a positive direction for potential/actual victims; what is needed is the prevention of perpetrators. Respect for the other is crucial.