Lehigh University has steadily increased its proportion of women to men attending, and the gender ratios in the university’s individual colleges have seen numerous changes since 2017. Despite that, there are still discrepancies between the different genders across the colleges and among the starting salaries of graduates.

Carly Dickerson, associate director of the Center for Gender Equity, said a school might have data that show a high percentage of women or members of underrepresented groups, but if the environment is hostile to them or they don’t feel they can get the most out of their degree as part of another group, that qualifies as gender disparity.

This fall, the Office of Institutional Data released data on “Selected Demographics,” which included information on student gender makeups across Lehigh’s colleges from 2017 to 2023, based only on men and women.

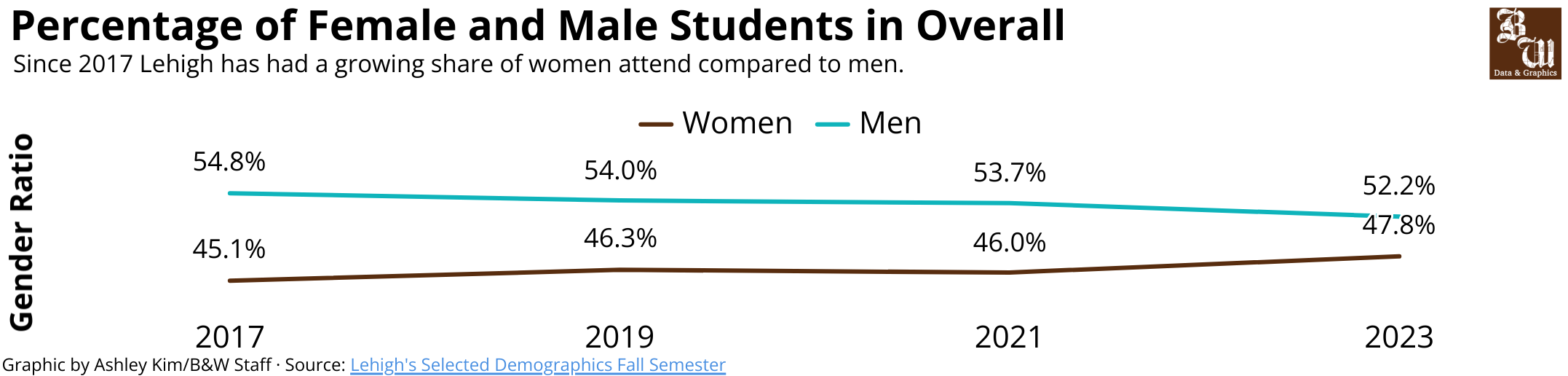

During this six-year time frame, Lehigh has seen an approximate 3% increase in the total enrollment of women — 45.1% to 47.8% — and total enrollment of men decreased from 54.8% to 52.2%, according to the office’s data warehouse.

Dickerson said the class of 2027 is the first incoming class comprised of more women than men.

Robert Flowers, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, said this increase in students who identify as women can be partly attributed to the college’s active effort to hire more women faculty members and to diversify the staff.

“I think a lot of it comes back to students who can then identify with someone who shares their experience,” Flowers said.

According to Data USA, Lehigh degrees in engineering, finance and computer science have been consistently given to more men, while marketing, management, education, administration, biology and psychology degrees have been consistently awarded to more women between 2017 and 2021.

Though industrial engineering and general finance are among the top five most common degrees awarded to both men and women between 2017 and 2021 at Lehigh, both degrees have a higher prevalence among men.

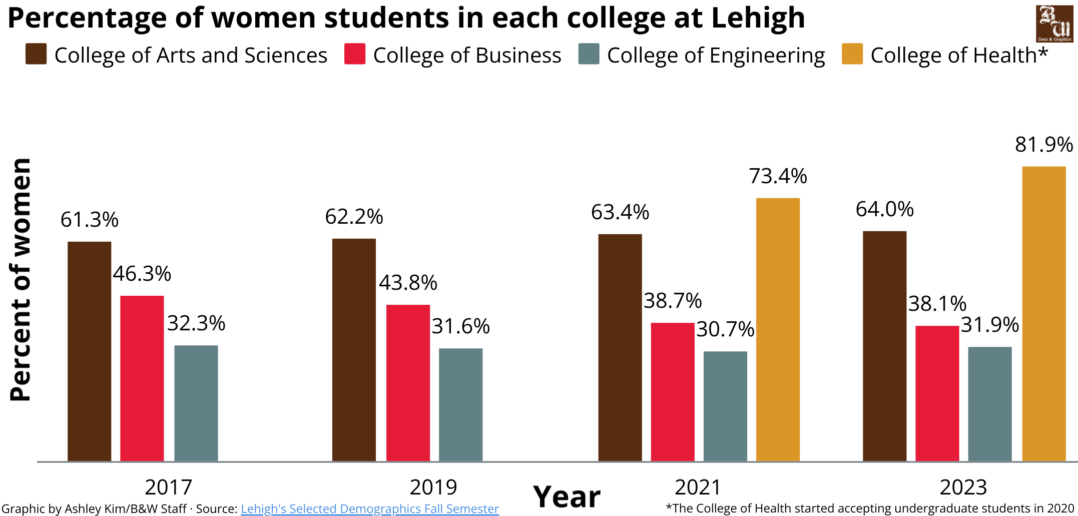

While the P.C. Rossin School of Engineering & Applied Science has been men-dominated since 2017, the College of Health and College of Education have remained steadily women-dominated during this time, according to the data warehouse.

Dickerson said at Lehigh and across the nation there are a lot of initiatives to bring more women into fields traditionally dominated by men like STEM.

She said it’s important to encourage women and people of different marginalized identities to apply to whatever field they are interested in, but it is equally important that these institutions are open and accepting for these people, especially through meaningful recruitment.

Sydney Volheim, ‘25, a student in the IDEAS program studying chemical engineering, said she thinks the chemical engineering major is the most evenly split major gender-wise in the engineering college.

However, she said the university could do more to try and promote the engineering school to women — perhaps through admissions events geared toward diversity among the various colleges.

According to the data warehouse, the College of Arts and Sciences saw an increase in the total percentage of women enrolled from approximately 61.3% to 64.0%. The total percentage of men enrolled in this college increased more significantly from 24.5% in 2017 to 37.5% in 2023.

Monica Najar, professor of history and also women, gender, and sexuality studies, has been teaching at Lehigh for the past 22 years.

For history classes, she said gender discrepancies can go both ways, but overall more women used to take the classes than men in the women, gender and sexuality studies department.

“You definitely could feel that some people were afraid it wasn’t a class for them,” Najar said.

She said things have changed in this department in the last five years — there are more people taking these classes, and the classes are more diverse, with an increasing number of men and genderqueer students.

Students are becoming more concerned with societal and political issues, Najar said, which coincides with many of the women, gender and sexuality studies classes.

“For instance, reproductive justice is not an issue for just people who identify as women,” Najar said. “All of these folks are wondering, ‘Where am I going to live?’ ‘Where and what laws are going to govern privacy in my home?’ ‘What kind of privacy will I have access to?’ ‘What kind of health care will I have access to?’”

Historically, Lehigh’s College of Business has been dominated by men. Recently, the college has seen an increase in gender imbalances. In 2017, the percentage of women in the College of Business was about 46.3% and fell to about 38.1% in 2023. Meanwhile, men increased from 56.9% to 63.5%.

Economics professor Fabio Gómez-Rodríguez said he thinks historically higher concentrations of men in certain majors discourage women from taking related classes.

“I think it’s a shame because we lose a lot of talent,” Gómez-Rodríguez said. “I think there’s sometimes a trend or a tendency for women to not try something they’re not sure they’re going to succeed. And again, I think we should work a lot on that because I think everyone should be confident of trying new things and different things, even though you’re not sure if you’re going to succeed.”

Economics professor Ahmed Rahman said his classes are composed of students in both the College of Arts and Sciences and the College of Business.

He said his classes are pretty balanced, but on average, he has noticed a few more men from the College of Business and a few more women from the College of Arts and Sciences.

Rahman said he thinks students overall prefer more collaboration in the classroom, but he said he has found women tend to respond better to that mode of teaching.

Dickerson said collaborative work is generally helpful, regardless of gender.

Rahman cited research showing women are more easily dissuaded from joining certain fields than men, and he suspects a big chunk of that is the nature of how people in those fields talk about ideas and collaborate.

“These are fields that are much more sharp-edged — that can be very dissuading for people,” Rahman said.

Dickerson said it can be argued that women are socialized to be more passive than men, but no one “can win” if people hold onto the idea that men and women have inherently different, gendered ways.

She said how people interact with others depends on the individual context, and buying into expectations of how men or women should act perpetuates gender bias.

“We should be thinking ‘How can we make these ‘sharp-edged’ or ‘harder’ fields more collaborative?’” she said. “I don’t think (a collaborative work style) necessarily needs to be a sign of weakness or deserving of less pay.”

Rahman cited a 2013 study that examines the impact of subpar grades on the selection of a major for men and women. To note, this study only examined the impact of grades for men and women.

According to the study, conducted by Claudia Goldin, Harvard economics professor and 2023 Nobel Prize recipient, a man is four times more likely than a woman to choose economics as their major after receiving a ‘C’ in an introductory economics class.

Dickerson said she is not surprised by this data.

“Mediocre men” versus “overqualified women” can both be considered for the same position, Dickerson said, yet women might feel they aren’t going to get it due to a perceived bias.

She said it is the responsibility of people in power to teach with this dynamic in mind rather than “blaming women for giving up too easily.”

The prevalence of men choosing certain colleges at Lehigh might also have an impact on gender disparities between the average salary for recent graduates.

Dickerson said those with in the business and engineering schools, both of which have a higher percentage of men than women, tend to go on to relatively high-paying jobs.

Whereas, education and health degree graduates, both of which Dickerson said are about 80% women versus 20% men, tend to be followed by traditionally low-paying jobs for the amount of labor being done.

According to Lehigh’s Undergraduate Outcomes Summary, the average starting salary of the 2022 graduating class was $75,000. Broken down by college, the average starting salary was $58,000 for the College of Arts and Sciences, $81,000 for College of Business students and $82,000 for the College of Engineering.

Rahman said certain industries have greater tournament-like competition for promotions and those environments tend to favor men. Though collaboration can be great for productivity, it can often make it hard to distinguish between those who are high performers and those who are not.

So if women are in more collaborative industries, Rahman said they may not get promoted as rapidly because it is more challenging to figure out who is contributing to what, which is one of the many possibilities as to why the gender gap persists.

“It could be that this collaborative nature, in some industries, doesn’t allow you to progress,” Rahman said. “It doesn’t allow you to move up the chain.”

Dickerson said when asking for references for graduate school or employment, the phrases that recommenders often use to talk about men compared to women often emphasize implicit biases.

“Their advisor might talk about these women like, ‘Oh, they support the team really well. They’re good team players,’ whereas a man might be described as innovative (or) taking charge,” Dickerson said.

Though they are all positive terms, Dickerson said they don’t give the same impression to a hiring firm or admissions staff.

Volheim said she has high hopes for the future of women in STEM-related careers though the start of it may be rough.

“You can get your degree, but then when you go into industry, it’s going to suck being a woman. That’s just the reality of it,” Volheim said. “I think it starts there, and promoting women to study these topics and having opportunities for them is important. I hope we can do that in the future.”

Dickerson said if women aren’t getting the support they need in fields dominated by men, they lack of support will continue to “trickle” throughout their careers.

She said feminism doesn’t mean there should be just as many women in every field as men, but rather women should receive equal opportunities in every field as men.

“We don’t need perfectly distributed numbers and everything to achieve it,” Dickerson said. “We need more equitable spaces.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.

2 Comments

The Lehigh problems addressed in this essay could be avoided by re-instituting the Lehigh that existed in 1970.

Please tell me how the soon to become majority women Lehigh has been good for the University, its students and its graduates. I believe it to be true but that is without evidence on which to base my belief beyond the fact that the number of women students has gradually increased.

What is the problem if men dominate Business & Engineering while women dominate the the arts & health sciences?

Seems normal to me!!