An upcoming accessibility app, MABLE, introduces new avenues of accessibility not just for Lehigh students, faculty and staff, but for individuals with disabilities worldwide.

MABLE represents Mappable for Accessible Built Environments. The app is being developed to map the interior of buildings and help people with disabilities navigate destinations with less difficulty.

Vinod Namboodiri, a professor of community and population health as well as computer science and engineering, was awarded Phase Two funding from the National Science Foundation’s Convergence Accelerator to continue the app’s development.

Namboodiri said his inspiration for creating the app comes from his own experiences and hopes it will improve accessibility in the future.

“As I was growing up, I had challenges seeing in low light, I had tunnel vision as the light faded,” Namboodiri said. “My visual impairments shaped me in some sense and made me wonder: how does a blind person move around?”

Students who find themselves getting lost in buildings will also be a target audience.

Lehigh’s mountainous campus, old buildings, stairwells and parking lots are a challenge to navigate.

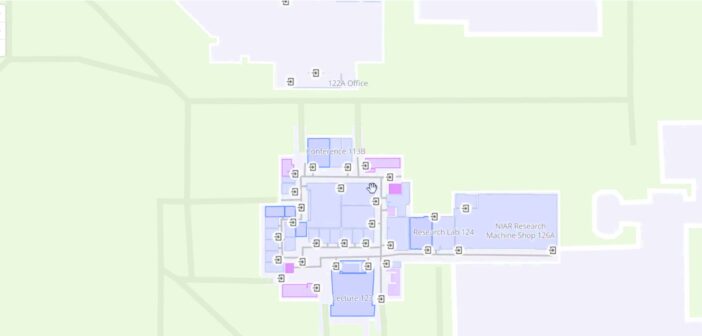

A screenshot of the upcoming MABLE (Mapping for Accessible Built Environments) app shows how users can input information about their needs and difficulties. Users can study interior maps before arriving at their destination and use the voice command function to lead them through the building. (Courtesy of Vinod Namboodiri)

Gianna Sottile, ’25, the Student Senate chair of Health, Safety and Wellness, said that Lehigh’s campus is not easily navigable.

“I think that it [the campus]needs to be greatly improved,” Sottile said. “I do not think our campus is accessible whatsoever.”

Sottile said the main concerns are not only the number of stairs on campus or its walkability, but also the fear that Lehigh services will not be responsive to students’ concerns with accessibility. She said she urges students to report and bring awareness to this issue.

“In my experience, I’ve had an easy time talking to administrators,” Sottile said. “I do encourage students that if they have an idea to make campus more accessible, to reach out.”

Heather Flyte, a graduate student and assistant at the Writing and Math Center in Drown Hall, said there are complications to Drown’s accessibility.

As the building is over 100 years old, Flyte said many staircases do not have railings or safety requirements.

“I’ve been here since 2018 and people have continuously complained things are not actively being pursued,” Flyte said. “Infrastructure is the challenge, it’s an old building.”

In the future, the app will be one way for students, faculty and staff to tackle these issues.

Similarly, Namboodiri said it’s not only the exterior of the campus that people struggle to navigate, but also the interior.

“It’s a lot of extra anxiety for those with disabilities,” Namboodiri said. “It’s difficult for blind people, sometimes people can’t even see the signs to navigate around buildings.”

The app will offer a way for people to see inside buildings and where they will be going beforehand so they can bring the necessary equipment they need.

The app is similar to Google Maps in form and has voice commands similar to Siri voice directions inside a building.

Namboodiri said he hopes one day it can be implemented into the HawkWatch app.

“We want to build maps with location information,” Namboodiri said. “Everyone often wants to know what’s in there, with the app you can study the interior before you go.”

Namboodiri also teaches a class about assistive technology, where his students learn that within the interior design of buildings themselves, many lack the convenience of shorter routes and lack consideration of those with impairments.

“I hope students can help improve it,” Namboodiri said. “In the future, we hope to change the designs of buildings completely.”

He said the app has been in development for around four years and he chose to bring it to Lehigh because of the passion students have to work on societal challenges. He said he hopes that more Lehigh students around campus become involved.

“We’re around (the) halfway point.” Namboodiri said. “We want to educate, not just build a product.”

He said the app’s development heavily depends on an interactive process and human subject testing. The testing is being conducted at the Good Shepherd Habilitation Center, the American Foundation for the Blind and the Smithsonian Museum of D.C.

According to Lehigh Communications, Phase Two lasts 24 months. Once Namboodiri and his team complete the phase, the app is expected to provide accessibility solutions at a much larger scale than just Lehigh.

“We want to provide the ability to personalize.” Namboodiri said. “Those with cognitive disabilities, intellectual, physical, it helps a broad base of the population, it helps everyone.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.