The Lehigh football team sold out its 160th matchup against Lafayette on Saturday.

It will be the first time college football’s most-played rivalry surpasses the 16,000-fan capacity at Goodman Stadium since 2013.

It also bucks an ongoing trend of dwindling attendance at Lehigh football games.

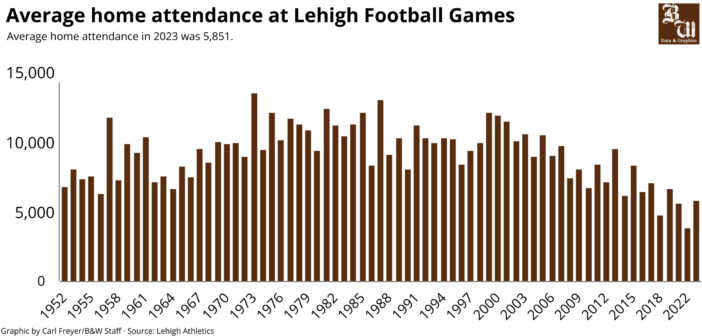

Since 2019, average attendance for Lehigh football home games, excluding The Rivalry, has decreased yearly. In 2022, the Mountain Hawks averaged 3,886 fans per home game, their lowest average attendance since 1952, excluding the COVID-shortened 2020 season.

The low attendance is emblematic of a variety of factors converging on one of the nation’s most storied football programs.

One of those factors is winning.

On Saturday, Lehigh football has the opportunity to capture its first Patriot League Championship and FCS playoff bid since 2017 after their last title dropped in attendance by over 1,000 fans per home game.

The 2024 season will mark the first time Lehigh football finishes with a positive point differential since 2016.

“I think success is what really does it,” said Charles Burton, ‘92, the founder of Lehigh Football Nation. “If you have a successful program, people will show up and they’ll support the team. When Lehigh was doing well and they’re playing Colgate (2005), two nationally ranked teams in the FCS, they were bringing in 12,000 people.”

Goodman Stadium, which is more than 10 minutes away from Farrington Square, has hosted the Mountain Hawks’ home games since 1988.

Since the move to Goodman Stadium, Lehigh football’s point differential has a .641 correlation to its average attendance.

During all 12 of the team Patriot League Championship seasons, Lehigh football has averaged 9,475 fans. From 2018-2023, support has averaged 5,388 fans per game, a cumulative -698 point differential.

After a Nov. 17, 1997 home win against Lafayette, Lehigh didn’t drop another contest at Goodman Stadium until their loss to Colgate on Nov. 9, 2002, picking up four consecutive Patriot League titles from 1998-2001.

The team’s previous home was Taylor Stadium, which sat where Rauch Business Center and the Zoellner Arts Center currently stand.

Lehigh averaged crowds of about 9,721 fans from 1952-1987. After the team’s move to Goodman to 2023, that number has fallen to about 8,775.

Richard Haas, the assistant athletic director for sales and marketing, said the distance has presented a challenge in student attendance at the games.

A bus runs from The Center for Dialogue, Ethics and Spirituality starting at 9 a.m. on game days, but some students have noticed issues with the system.

“I’ve arrived late on multiple occasions due to how infrequent the buses come back to campus,” said Clutch, Lehigh’s student mascot.

Clutch said one time they were waiting 45 minutes for a bus to return to campus.

“The distance matters,” Haas said. “I think if the environment and the event is big enough, and it’s popular enough, everybody gets there. Yes, it’s far, I don’t think it’s worth making the effort.”

Haas also said the decline in tailgate culture at Goodman Stadium, an issue that he said began to take shape from 2015-2019.

“It used to be that the tailgates were all on site,” Haas said. “Tradition was you come over, you tailgate, you go to the game. But at some point, a couple (Greek organizations) said, ‘Hey, why don’t we just tailgate at the house, and then we’ll go to the game?’ And they would do that. And then at that point, it just takes a couple to say, ‘What if we just tailgate and we don’t go?’”

Burton said he believes crackdowns on underage drinking at tailgates incentivized students to stop.

“I know that they had increased tailgating rules,” Burton said. “It was a little more free-wheeling back in my day. As that got cracked down, I think the students got less and less enthusiastic about coming.”

However, Keith Groller, The Morning Call’s reporter for Lehigh football, said the stadium move also impacted the number of South Side residents attending the games.

Groller said Taylor Stadium was “tightly packed” and had limited parking, but it had a neighborhood feel that Goodman Stadium lacks.

“It was an attraction to South Bethlehem,” Groller said. “Back then, there was not much going on in that part of Bethlehem, so Taylor Stadium on a Saturday, especially when (a team) like Delaware would come in, it was tremendous.”

As the South Side continues to grow, other attractions begin to drown out the entertainment value of a Lehigh football game, Groller said.

He also said with the advent of ESPN+ and the increased national coverage of bigger FBS games at the expense of smaller schools, Lehigh football continues to lag behind in viewership.

“There was no SEC Network. There was no Big 10 Network,” Groller said. “It was the thing to do. There was no ESPN+. Obviously, in the early ‘70s, it was just a different world, and Lehigh football had its niche. It was very popular, win or lose.”

In the ‘90s, Lehigh football games were often broadcast on Service Electric Network or Channel 69, a luxury that not many schools in the area had.

Now that almost all school games are available to stream nationwide, Lehigh football’s niche has become obsolete.

The attendance issues are not just a Lehigh problem — they’re affecting the entire Patriot League.

Groller said the supremacy of bigger leagues and the Patriot League teams’ unwillingness to field rosters that can compete on a national level pose problems for attendance.

“I think it’s always been academic,” Groller said. “They never seem to really care about having teams that will compete,” Groller said. “They (restricted) scholarships for years and (kept) the roster sizes restricted.”

In matchups against Lehigh, only Holy Cross averaged more than 5,000 fans since the league’s inception in 1986.

In home Patriot League games excluding Lafayette, Lehigh has averaged just under 8,000 fans since 1986.

The league’s lack of meaningful competitions could potentially affect its historically low attendance.

Burton said the Patriot League’s top-heavy nature prevents rivalries from brewing due to a lack of competitiveness.

Aside from Le-Laf, Lehigh previously had a competitive rivalry with Delaware. The pair played in the Middle Atlantic Conference during the 1960s and then continued their competition as Division II independents in the ‘70s and earlier ‘80s.

The 1990s saw the last great period of this particular rivalry, which was ignited by the legendary Blue Hens coach, Tubby Raymond.

“(Raymond) had a special thing against Lehigh and Lehigh had a special thing against him,” Burton said. “There was a lot of hatred between the two.”

Before the teams’ 1999 matchup, Burton said Raymond referred to Lehigh’s Patriot League schedule as playing against “the sisters of the poor.”

“As an alum…bigger, badder Delaware and small, little Lehigh on a hill came down there and beat them — what a satisfying victory that was,” Burton said.

Lehigh’s eight home matchups against Delaware drew an average of 12,588 fans.

Burton said the programs had a disagreement about Delaware traveling to Bethlehem for certain games.

The teams’ last meeting was a 42-20 Delaware victory in the 2010 FCS playoffs.

Next year, Delaware will make the move up to the FBS, leaving Lehigh and other smaller schools with declining attendance in the dust.

Groller said the “glut” of FBS football is causing this decline, and Patriot League programs are complacent when it comes to improving their attendance figures.

“(Patriot League schools) don’t draw,” Groller said. “It hurts. It’s hurtful, it’s disgraceful, it’s embarrassing and they don’t seem to care.”

Many solutions have been pitched, such as pushing back start times or adding stadium lights for night games, but due to the multifaceted nature of the problem, finding a solution will not be that simple.

“We’re making sure that we’re connecting me with student leaders, and with opinion makers, and people who are connected and can give us information on what students want and how to market best of them,” Haas said. “I think it’s really important as we move forward.”

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.