After being sentenced to 24 and a half years in prison for the distribution of drugs, a crime she did not commit, Kemba Smith knew her story was far from over.

An author, activist and mother, Smith is featured in the film “Kemba.” It tells her story as a formerly incarcerated person, as well as those of many other women in the United States.

Students, educators, community members and activists gathered in the Black Box Theatre at Lehigh’s Zoellner Arts Center on Thursday to watch and discuss the film “Kemba.”

Leaving many attendees in tears, the film shed light on the life of Smith and the sentencing disparities in the U.S. legal system.

The movie was one of five shown in an inaugural series hosted by Lehigh’s Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration Committee. Sixty years after King’s “I Have A Dream” speech, the committee works to engage the community beyond Lehigh’s campus, addressing social justice issues and spreading knowledge on movements that have inspired change, according to its website.

John Vilanova, a journalism and Africana studies professor, and Mel Kitchen, coordinator at the Pride Center, led the movie series with the support of other committee members.

Vilanova said the films were selected to reflect the giant triplets of racism — a focal point of King’s 1967 speech at Stanford University, “The Other America.”

“We wanted people to propose films with those things in mind,” Vilanova said. “It felt important to us that people develop structural and intersectional understandings of oppression.”

The featured movies for the 2024-2025 series include: “The Battle of Algiers,” “Toxic: A Black Woman’s Story,” “Las Abogadas,” “Kemba” and “Slavery in the Age of Revolution,” which will be screened on March 25 at the SteelStacks.

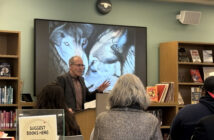

Following the movie, a panel of guest speakers was invited to discuss questions, moderated by Aika Aluc, a second-year doctoral student at Lehigh.

Aluc said academia has a way of supporting people, shaping how they think and process things, and influencing how they create new ideas and challenge existing ones.

“I hope that we have more spaces to gather, more spaces for collective activism, and more spaces to continue to champion narratives and stories that sometimes don’t always have a microphone,” Aluc said.

The panel included Holona Ochs, a political science professor; Fatima Wakeel, a population health professor and previously incarcerated woman; Tabatha Trammell, founder of the nonprofit organization Women with A plan; and Hasshan Batts, executive director at the community organization Promise Neighborhoods of the Lehigh Valley.

Together, they navigated topics such as maternal resilience, mental health and incarceration. They also discussed transitioning back to life after incarceration, and cycles of economic mobility and opportunity in Black communities.

Ochs highlighted the importance of storytelling and creating space to share stories like Smith’s, and among others. She said as a political scientist, she’s learned that these systems are predictable.

“All of this is by design,” Ochs said. “We frame some people as dangerous and punish them. The only time I have noticed people changing their hearts with it was when we made space for people who have lived that experience to tell their experiences.”

“Kemba” also shares the story of a friend Smith met in prison, Michelle West.

West, another victim of the legal system, was offered clemency last month after 32 years in prison under the mandatory minimum sentence law. This law requires judges to impose an automatic prison sentence for certain crimes, not taking into account how specific details or nuances pertain to an individual’s case.

According to the National Research Council’s 2014 report, “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States,” studies have found mandatory minimum sentences have minimal effects in reducing crime.

Studies have also shown that minority groups tend to receive these sentences at a disproportionately high rate. For example, in 2019, people of color made up 91% of arrests in New York for crimes with mandatory minimums.

Smith was initially planning to attend the film screening at Lehigh. However, given the timing of West’s clemency, she took time to be with West as she transitioned back into her home with her daughter.

Smith recorded a video to be played after the movie, sharing additional insight about her experience.

“It’s been my commitment to continue to push forth sensible, smarter policies and to ultimately bring people home to their families,” Smith said in the video. “I actually gave birth to my son while I was incarcerated, and I do think society needs to focus on the impact on children in humanizing more stories, in particular women.”

She said her parents played a significant role in supporting her throughout her clemency process and, ultimately, the reunification with her son. She also said therapy has allowed her to maintain positive relationships after prison.

Many foundations are available to help individuals in similar situations. The Legal Defense Fund, Represent Justice and Promise Neighborhoods of the Lehigh Valley are a few which work toward justice and offer support for incarcerated individuals.

“Regardless of whichever level you are at or the type of work that you do, I think there’s always more for us to learn in other ways that we can be connected to one another,” Aluc said.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.