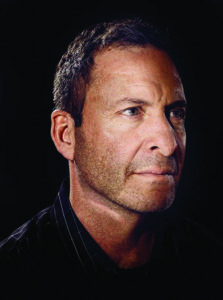

Clint Malarchuk spoke at the Zoellner Arts Center about mental health. The former professional ice hockey goaltender has written a book about his career and struggles. (Courtesy of Clint Malarchuk)

Note from the editors: The following story contains issues related to mental health and suicide.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 800-273-8255.

On March 22, 1989, Clint Malarchuk suffered one of the most horrific injuries in the history of professional sports.

A skate sliced his carotid artery and partially sliced his jugular vein.

The trauma from that day changed his life and led him to dedicate his career to talking about mental health.

Malarchuk came to Lehigh on Sept. 10 to speak at the Zoellner Arts Center on National Suicide Prevention Day.

At eight years old, Malarchuk realized he experienced more anxiety than the rest of his friends.

That anxiety caused Malarchuk to have deep insecurities, which manifested into in an obsession to be perfect.

As a child growing up in Canada, his obsession translated to playing hockey as many hours a day as he could, Malarchuk said.

“I never thought I had that much talent,” Malarchuk said. “Although looking back, I did have talent, but at the time, I really didn’t think so. I was really insecure. I thought I had to outwork and overdo everyone.”

As a child, Malarchuk worked out four to six hours a day no matter the season. Despite temperatures as cold as fourty degrees below zero on the coldest days in Canada, Malarchuk said he never missed a day of hockey workouts.

Malarchuk’s anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder continued to worsen as his childhood progressed.

Malarchuk was hospitalized for two months at 12 years old because he was continually becoming overcome with panic.

“All (the hospital) would do is sedate me when I would get overcome with panic or anxiety,” he said. “They released me after two months and said, ‘good luck mom, he’s a real anxious kid.’ There was no therapy.’”

Despite his anxiety, Malarchuk’s work ethic and natural talent led him to the NHL, where he had a 15-year career as a goaltender, earning the nickname the ‘Cowboy Goalie,’ because of his love for horses.

Malarchuk’s career and life changed when the St. Louis Blues came to Buffalo to play Malarchuk’s team, the Sabres.

While Malarchuk was in goal, Blues player Steve Tuttle collided with Malarchuk’s teammate right outside the crease, and Tuttle’s momentum carried him toward Malarchuk. Tuttle hit the floor and his skate popped up, slicing Malarchuk’s neck, severing his carotid artery and partially cutting his jugular vein.

Malarchuk said he wanted to get off the ice as quickly as possible because he knew his mother was watching the game, and he didn’t want her to see him die on television.

Despite a near death experience, Malarchuk came back 11 days later against his doctor’s orders.

“You get bucked off a horse, you get right back on,” Malarchuk said.

After the incident, Malarchuk’s mental health began to deteriorate, he said.

The next three years, Malarchuk went to different specialists to try to find the right medication to help his mental health, but nothing was working.

The trauma from the accident triggered his depression and anxiety to a higher level than it had been before, Malarchuk said.

After three years Malarchuk got sent to the minor leagues and saw a leading specialist on depression.

“It was devastating getting sent to the minors, but it was a blessing because I got to see this doctor in San Diego,” Malarchuk said.

The specialist recommended a medication that changed Malarchuk’s life. It worked for 15 years until his body became immune to the medication.

Around the same time Richard Zednik, a player on the Florida Panthers, suffered a similar injury to Malarchuk in an NHL game.

At the time of Zednik’s injury, Malarchuk was coaching in the NHL. Due to NHL rules, all coaches were forced to have media availability.

The media pestered Malarchuk with questions about Zednik’s injury, which triggered Malarchuk’s own trauma.

“I had undiagnosed PTSD,” Malarchuk said.

Malarchuk began to self-medicate with alcohol to cope with the trauma of the injury.

The spiral of Zednik’s injury and unresolved trauma lead Malarchuk to attempt to commit suicide, he said.

After the suicide attempt, Malarchuk spent six months in a rehabilitation facility in the San Fransisco area.

The facility put Malarchuk on a new medication that helped him feel as good as he did during the time he was on the medication prescribed by the doctor in San Diego.

“I remember thinking, ‘wow, I’m back,’” Malarchuk said.

Since leaving rehab, Malarchuk has written a book about his journey and is now dedicating his life to talking about mental illness by speaking at events around the country.

Malarchuk said these experiences do not make him relive his old trauma like the press conferences did after the Zednick injury. Instead, they are cathartic, as he knows it is helping someone else going through the same internal pain.

The Cowboy Goalie now resides with his wife Joan Alissa Goodley in Nevada, traveling to speaking engagements and working as a horse dentist.

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.