After a painful root canal, a patient might be given oxycodone, a type of opioid typically prescribed after dental procedures. Amidst the numbing pain from the procedure and the stress of medical bills, the patient fades away into the euphoric state that is an opioid high. Suddenly, the patient cannot function without them and they feel excruciating pain. After being cut off by their doctor, the patient takes to the streets to find something to make the pain go away: heroin and fentanyl.

Heroin is an opiate drug derived from the opium poppy plant, and fentanyl is a synthetic, potent opiate often added to heroin or used as a stronger alternative.

The opioid epidemic has been devastating the United States since the 1990s.

Opioids were originally prescribed to block pain from patients undergoing medical procedures. While blocking the pain, the drug also creates a euphoric high that is easily addictive. People become reliant on the drug and feel pain without it. As a result, people start to take higher doses or seek out potent alternatives.

In 2020, there were 68,630 deaths tied to opioid usage across the United States, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This makes up 74.8% of all drug-related deaths nationally.

“They make your brain change, and they make your brain think that it needs opioids to survive,” Lehigh EMS member Katherine Stenersen, ‘24, said. “When your brain is telling you something, it feels just as real as anything else.”

In Pennsylvania, there were 5,168 opioid-related deaths in 2020, according to the CDC, which made it the state with the fourth highest number of deaths.

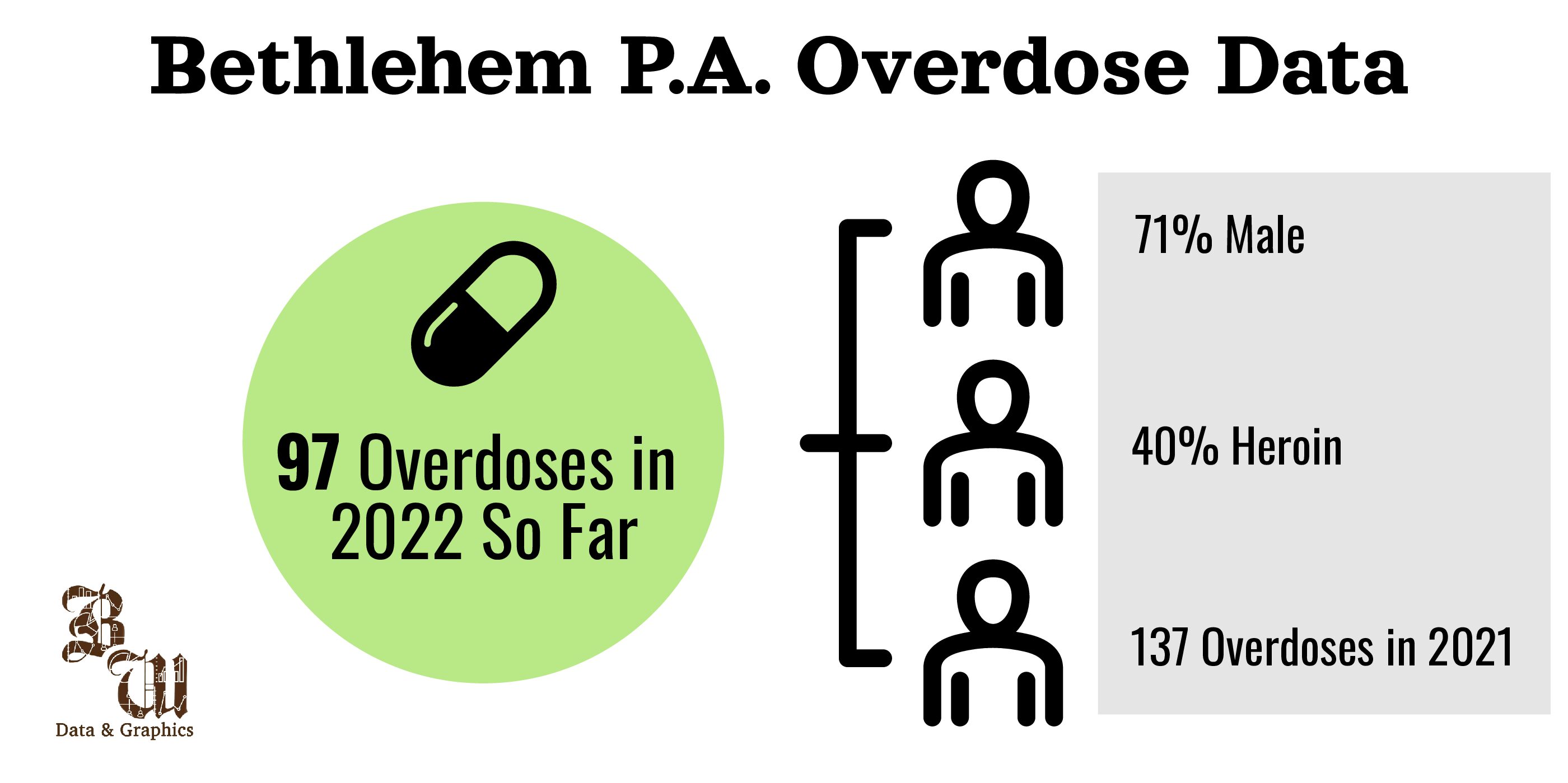

The opioid epidemic is present and thriving in the Lehigh Valley. In 2022, there have been 97 opioid overdoses so far in the area, according to the Bethlehem Health Bureau.

The Lehigh Valley’s close location to New York City and Philadelphia, both having high concentrations of opioid usage, “helps drugs flow through easily,” said Capt. Nicholas Lechman of the Bethlehem Police Department.

In 2021, there were 2,300 overdoses in New York, according to the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor of New York. In Philadelphia, there were 1,214 deaths in 2020, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

“Folks that are prescribed something after a dental procedure or surgery will often end up getting hooked and transition to street-level drugs or prescription drug abuse due to the addictive nature of these pills,” Lechman said.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro announced charges against 15 suspects on Oct. 7 at the conclusion of a six-month investigation into the trafficking of opioids into Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The investigation was conducted by the Bureau of Narcotics.

“These individuals have profited from selling dangerous drugs that fuel the opioid epidemic and devestate our communities,” Shapiro said in a statement.

Even though police forces across the Lehigh Valley are working to get opioids off the streets, police and EMTs are prepared to treat overdoses.

One common drug used to treat overdoses is Naloxone — commonly known as Narcan.

“Here in Bethlehem, we’re trying to take a proactive approach to this issue,” Lechman said. “For instance, our officers are carrying Naloxone, which is designed to rapidly reverse an overdose, especially with opioids.”

He said opioids first affect the breathing of an individual, and an overdose can stop their natural respiration.

“We administer Naloxone as early as we can to try to reverse those effects and prevent someone from going into respiratory arrest, which leads to cardiac arrest,” Lechman said.

EMTs across the nation are taught to expect an opioid overdose as a common call, Stenersen said.

Narcan isn’t a long-term solution, though. Stenersen said the drug will wear off and an individual experiencing an opioid addiction can overdose again if they are not properly treated.

If someone survives an overdose, there is no set plan in place. Local police departments have individual protocols to ensure patients are safe and aware of treatment options.

“We also have what’s called the Blue Guardian Program in the area,” Lechman said. “After we respond to an opioid overdose, over a period of time, we’ll return to the individual — if we know where they are — and follow up with them by offering treatment options to help break the addiction cycle.”

Lechman said his department is having some success trying to directly address the opioid issue with Naloxone and the Blue Guardian Program.

The Bethlehem Health Bureau leads the Northampton County Heroin and Opioid Overdose Task Force.

“As part of these efforts, heroin and opioid overdoses and overdose death data are collected and analyzed in order to identify specific trends,” said Kristen Wenrich, City of Bethlehem Health Director.

There has been a part-time drug task force for the past 20 years at the county level. The dire drug problem in Northampton County led District Attorney Terry Houck to introduce a full-time county drug task force this year.

Full-time drug task officers will now receive specialized training to improve their ability to investigate the distribution of illegal drugs and their impact on the local community.

“The population of people who have opioid addiction is growing in the United States,” Stenersen said. “There’s now a lot of money and research and efforts going into preventing opioid addiction in the future.”

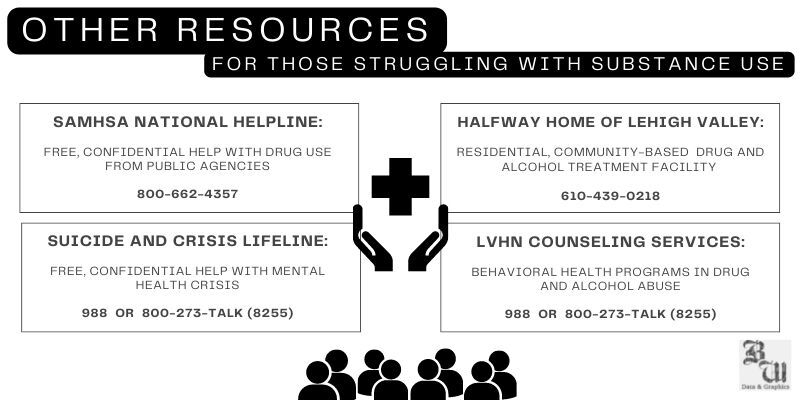

The resources listed above are available for those who struggle with substance abuse. Police and EMTs are working to stop opioid usage but are prepared for overdose situations. (Sam Barney-Gibbs/B&W Staff)

Comment policy

Comments posted to The Brown and White website are reviewed by a moderator before being approved. Incendiary speech or harassing language, including comments targeted at individuals, may be deemed unacceptable and not published. Spam and other soliciting will also be declined.

The Brown and White also reserves the right to not publish entirely anonymous comments.